Increasing Agricultural Conservation Adoption through Water Quality Sampling

Free and Anonymous Tile-monitoring for Farmers in the WLEB

Updated February 2nd, 2024

Since 2016, the Michigan State University Institute of Water Research (MSU IWR) has been documenting water quality in tile drainage in partnership with Adrian College, the Erb Family Foundation, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD), local conservation districts and participating farmers within the Western Lake Erie Basin (WLEB). The main objective of this research has been to empower farmers with the ability to have better control over nutrients leaving their field using the water quality data provided to them, and ultimately, increase farmer interest in implementing best management practices (BMPs) on vulnerable land throughout the watershed.

This work has evolved over the course of three phases:

Phase I (2016–2018)

To increase farmers' knowledge about nutrient loss and promote the adoption of BMPs, a free and anonymous tile-monitoring program was established in the South Branch of the River Raisin watershed as part of a master's thesis project. Farmer participants (n = 3) provided a total of five tile drains to be studied. Weekly grab samples were collected for approximately 18 months and the data was compiled into water quality reports. These reports were kept confidential and provided only to the respective participant farmers at the end of the study. The data provided included nitrate (NO3-N), total phosphorus (TP) and soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP) concentrations and loads, and flow. Additionally, in-depth interviews were conducted both before and after the participants received their water quality data to document changes in thoughts and behavior toward conservation. The post study interviews revealed that farmers became more aware of nutrient loss occurring on their fields, particularly during times of the year they did not expect to see losses (i.e. during the winter season). Post interviews also revealed a shift in each farmer’s perceived ability to control nutrient losses, with each farmer’s solution being specific to their unique operations. These results support the ideology of using outcomes-based conservation versus the standard “on size fits all” approach.

Additionally, a survey was conducted at a farmer-led watershed meeting to gain insights regarding the perceived usefulness and need for this type of information on a 1-10 scale. Eight farmers participated in the survey and responses revealed that farmers were generally very supportive of using tile drain data to help make on-farm conservation decisions, with the average response score to these questions being above eight.

For more information about this phase of the study, please see:

Phase II (2019-2021)

As a continuation of the pilot-program established in 2016, the Erb Family Foundation provided additional funding to expand the program in 2019. Three farmers were added to the tile monitoring program (bringing the total number of farmer participants to six). Participants received water quality reports after approximately 6-12 months of data collection (depending on when the farmer joined). Qualitative interviews were conducted with participants to gather insights on how water quality data as a feedback mechanism can benefit the conservation mission and potentially increase farmer interest in adopting best management practices (BMPs). Study findings highlighted multiple benefits to this cause, including producers recognizing water quality concerns they were otherwise unaware of, producers feeling more confident in the BMPs they already had in place and wanting to expand these practices onto additional acreage, and participants wanting to share their results and discuss the benefits of BMPs at farmer-led meetings. Results suggested that incorporating anonymous grab sampling into today’s conservation adoption strategy could be a helpful tool for starting positive conservations about BMPs and getting producers more invested in the problem-solving process.

Additionally, a second survey was distributed during this phase to farmers (n = 91) within three Michigan watersheds (Lake Macatawa, Saginaw Bay and the Western Lake Erie Basin) to determine the interest level in an anonymous tile monitoring program. This survey was advertised online within two newsletters put out by The Nature Conservancy in December of 2020 and January of 2021. It was found that 73 percent of respondents were extremely interested in joining an anonymous tile monitoring program and 95 percent of respondents were extremely likely to adopt a conservation practice if high nutrient levels were found in their tile drain.

Phase III (2023-2025)

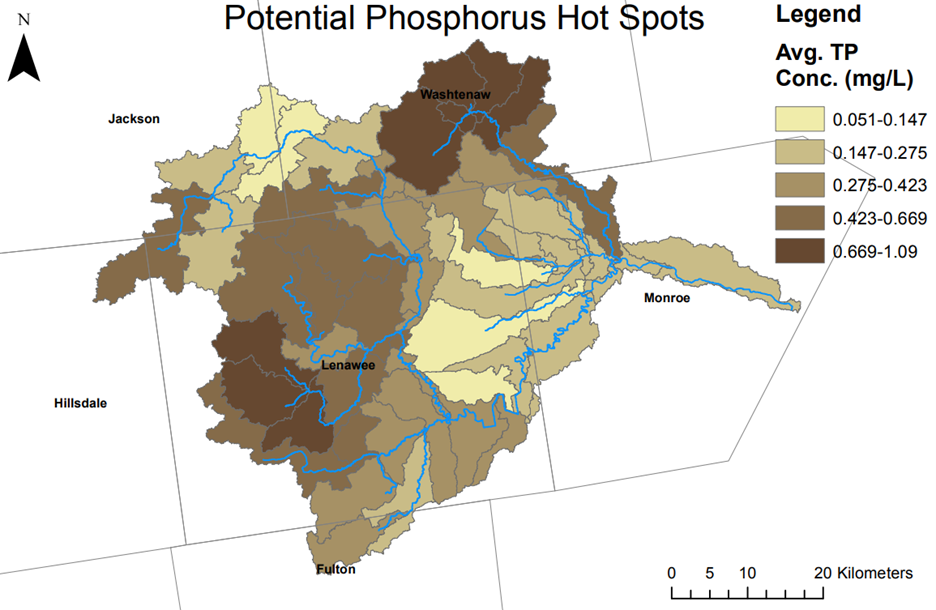

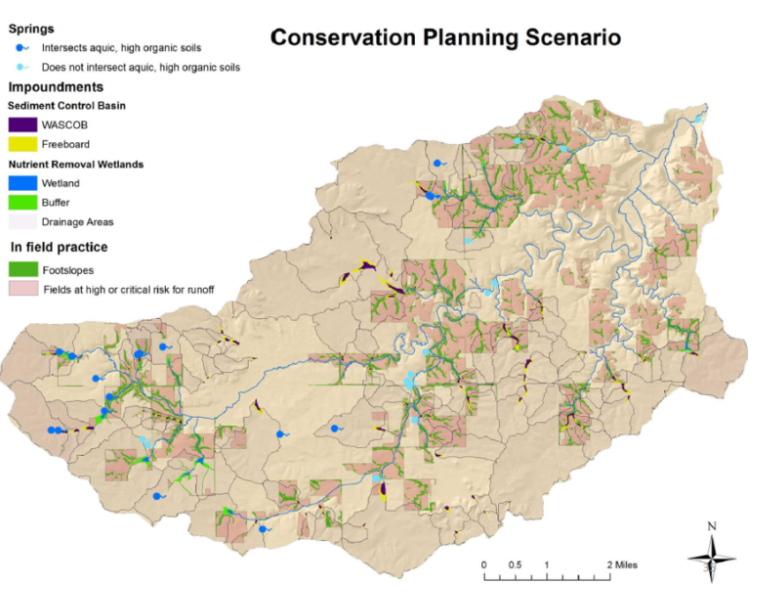

In collaboration with the Erb Family Foundation, MDARD and local conservation districts, the IWR is continuing to offer tile monitoring services within the WLEB. This phase will focus on employing a more targeted approach using local conservationist specialists, the soil and water assessment tool (SWAT) and the agricultural conservation planning framework (ACPF) as ways to identify and engage with farmers on fields most vulnerable to nutrient loss.

MSU IWR-generated SWAT map of TP hot spots throughout the WLEB.

Example of an ACPF result. Photo credit: https://acpf4watersheds.org>toolbox

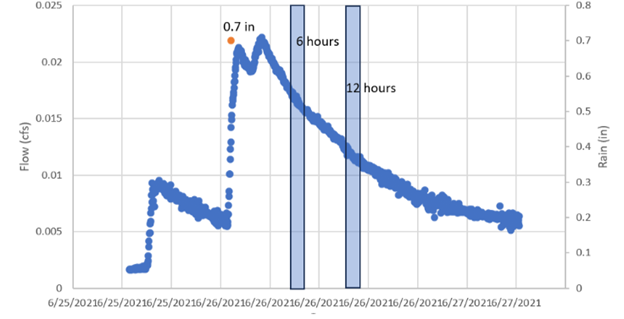

Grab samples are being collected based on storm or thaw driven events, as opposed to on a weekly basis as they were in the past. These samples are collected within 6-12 hours of a rain event (0.5 inches or more). While this will likely be an under-representation of the peak loading during each event, we believe this is the best grab-sampling method for capturing part of the run-off event, as opposed to responding within 24 hours when the entire event would likely be missed. This, of course, will vary from field to field; however, without continuous flow monitoring equipment this method provides the best opportunity to obtain the most valuable information we can provide to farmers at a reasonable cost.

Hydrograph depicting the importance of sample collection timing after a rainfall event of 0.7 inches.

For more information, please contact:

Alaina Nunn (Johnson)

Or contact your local Conservation District:

Print

Print Email

Email