A Great Lakes gold rush: Invasion of a costly clam

The golden clam was first reported in the Great Lakes region in 2001.

The golden clam, also known as Asian clam or Corbicula, is a small, round clam (less than 2 inches) with notable concentric ridges. Young invasive freshwater golden clams can look similar to native fingernail clams, but can be distinguished by having serrated ‘teeth’ along the inner edge of the shell near the hinge of the invasive species.

Reported in Great Lakes region in 2001

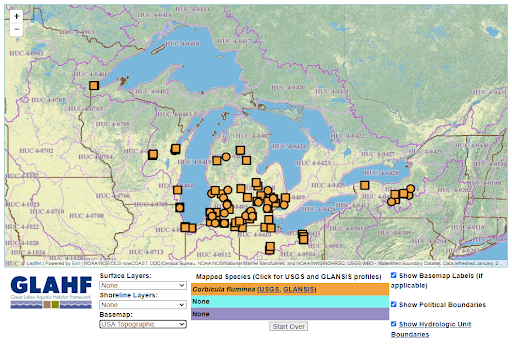

Native to tropical regions of Asia, the golden clam first appeared in the United States in the 1930s. It was either imported directly for people to eat or as a hitchhiker with the giant Pacific oyster, which was used for food around the same time. The clam species spread slowly across the United States through aquaculture, live food markets, bait, and carried downstream through watersheds. Mature golden clams are unique because only a single individual is needed to start a new population. The golden clam was first reported for the Great Lakes basin in 2001 in Lake St. Clair, but has rapidly spread and now is found in nearshore areas of all of the Great Lakes except Lake Huron.

Originally a tropical species in its native range, the Great Lakes region is at the northern edge of the golden clam’s temperature tolerance. Winter die-offs happen often but are not enough to limit the spread. Currently, most overwintering populations are in areas that provide artificial heat, such as near power plants and wastewater treatment plants. However, there is also evidence that golden clams are evolving to tolerate colder temperatures: some taken from northern populations have twice the survival rate of those from southern populations when exposed to near-freezing temperatures. Warmer winters will also contribute to this species’ success in invading the Great Lakes.

An expensive invader

The golden clam has been an extremely expensive invader in the United States. The cost of removing them from water intakes and power plant cooling systems is estimated at over a billion dollars per year nationally. Smaller populations in the Great Lakes - and management strategies already in place to combat zebra mussels - have so far led to lower direct costs, but if their population keeps growing, costs are likely to increase here as well. Some of the environmental impacts of this invader in the Great Lakes include increasing the impact of zebra mussels on water quality, lake bottom structure, nutrient cycling, native clams, and the food web – especially in the nearshore portions of the lakes.

Reports of golden clams in the Great Lakes basin are scattered throughout the region, but official reports are not enough to know how many have spread to inland lakes and other habitats. Scientists believe the clam prefers waters less than 10 feet deep with sandy or gravel bottoms, and that their ability to survive through winter is rare if waters fall below 5 degrees.

How can you help?

If you see what you believe are freshwater golden clams, please take a photo (including an object like a coin for scale helps us to verify the species) and note the location and date, then submit the sighting either by email to Rochelle Sturtevant of the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS) at Rochelle.sturtevant@noaa.gov, or online at the Nonindigenous Aquatic Species website or by using the Nonindigenous Aquatic Species app for Android.

A final note on the name of this species

- Corbicula fluminea is most commonly known as the golden clam or Asian clam, but efforts are underway to change this species’ common name to “freshwater golden clam” to avoid confusion with marine species.

- Learn more about this species through its online profile at the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This article was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA180AR4170102 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statement, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email