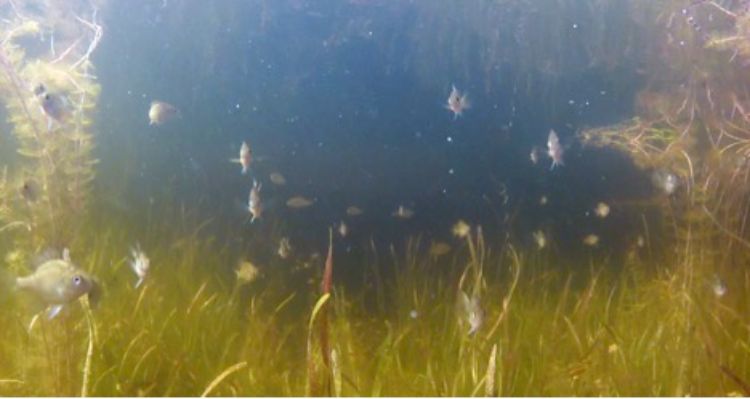

Aquatic plants provide shelter for young fish

A single acre of aquatic vegetation can hold hundreds of thousands of small fish.

I remember sitting on a dock as a boy, looking out over a small inland lake in northern Michigan and daydreaming about all of the fish that must be swimming down in the depths, far out of casting distance from shore. Out there beyond the weedline seemed like the perfect place to catch more fish. When I finally got out on a rowboat and tried fishing open water it was a big disappointment. Instead of catching dozens of small sunfish and the occasional bass or pike off of the dock, I caught absolutely nothing.

Decades later, I have a much better understanding of why. Most inland lakes support the growth of aquatic plants only in the shallow nearshore areas of the lake. These shallow ‘littoral zones’ are extremely important in part because they provide cover that enables small fish to hide from predators. Many gamefish (like bass) prowl along weed edges because they cannot feed very effectively in dense vegetation.

Of course, shorelines are also important areas for recreation. Aquatic plants are sometimes viewed as a nuisance by boaters and swimmers. Aquatic plant management is a common practice, but removing vegetation can be very detrimental to some fish species. A few species (open-water fish like shad, for instance) can actually benefit from plant removal, so what is the bottom line when it comes to impacts on fish?

The net effect

While there may be some winners and some losers, vegetated areas typically hold more fish than weed-free areas. In fact, they hold a lot more. A study conducted in the Pentwater Marshes found that vegetated shallows held 10 to 100 times as many young fish as weed-free areas. The study, which was funded by Michigan Sea Grant, noted that a single acre of aquatic vegetation produced 22,400-126,800 minnows, 34,400-113,200 bluegill and other sunfish, 760-2,280 northern pike, and 560-1,040 yellow perch per year. A review of the scientific literature on interactions between vegetation and fish found that total fish densities in vegetated areas range from 6,000 to 800,000 fish per acre. That is a lot of fish!

What about invasive plants?

Non-native species like Eurasian watermilfoil and curly-leaf pondweed can crowd out native vegetation and degrade fish and wildlife habitat. One issue that fish face is extremely high stem density. In other words, plants like milfoil can become so dense that only very small fish can hide and forage effectively among the stems. Growth rates can suffer because small fish become overabundant if predators cannot reach them.

A variety of chemical, mechanical, and biological control methods are available, but lake managers can sometimes be overzealous in attempts to eradicate invasive plants. State-developed guidelines for vegetation management in Michigan and Minnesota note that removal programs can eradicate native plants along with invasives. This can leave habitat open to re-colonization by the most aggressive invaders.

If non-selective vegetation removal continues on an ongoing basis the effects can be even worse. The Minnesota recommendations note that although native plants do provide better habitat than non-native invaders, the invasive plants are better than no plants at all. After all, habitat degradation is preferable to all-out destruction. In some cases (particularly in shallow, nutrient-rich lakes) the decreased water clarity that results from vegetation control spurs algae growth that prevents re-growth of native vegetation in a “catastrophic transition.”

Invasive species have caused untold damage to aquatic ecosystems and coastal communities, but control programs should always be carefully evaluated to ensure they do not cause more harm than good. For more information on aquatic plant management from Michigan State University Extension, see previous articles on control methods, ecological effects, and interactions between plants and bluegill.

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 33 university-based programs.

Print

Print Email

Email