Compost in Communities Part 1: A View of Vermicomposting in Kent County

This article is the first in a series exploring a variety of compost systems and their benefits to local communities. This exploration into vermicomposting examines the benefits of using worms in composting.

Composting is an increasingly versatile industry with a variety of methods to process food, manure, and other organic waste into nutrient dense soil amendments through controlled decomposition and management. The scale of composting systems varies from backyard piles to acres of commercial operations. Through this series, we will be exploring compost's impact on local communities and how compost can play a role in community sustainability and food systems. The first compost system of focus is vermicomposting, used by Kent County business, Wormies.

The process of vermicomposting is the use of worms to compost food waste. Worms add beneficial life to compost that other methods do not, such as introducing higher counts of microorganisms into the piles and processing food waste biologically through the worm's digestive system. Research from the National Institute of Health shows that vermicompost is generally higher in nutrients than regular compost and provides benefits to soil physically, chemically, and biologically. Vermicompost requires different environmental conditions such as cooler temperatures, careful monitoring, and needs a refined sifting process to remove adult worms and their small eggs. At Wormies, their composting systems account for all of these factors and result in creating a nutrient-dense compost that they then back to their community member subscribers.

The composting process at Wormies begins by creating thermophilic hot compost piles from the fresh food brought in from their subscribers. Thermophilic piles, or “hot compost” is a method of composting that requires large volumes, over 4ftx4ft in minimum size, and reaches a temperature of 130 to 160 degrees Fahrenheit. Heat is the key component in a thermophilic pile. This high-heat stage is the “pre-cooking” step to process the food waste at Wormies, and kills off any harmful pathogens in the compost pile before introducing the worms.

These hot piles are created from the collected food scraps, mulch, and bio char that they create on site. The addition of biochar at this initial stage adds crucial carbon content to the piles as well as reduces the smell of the pile when food is still visible and decomposing. Carbon is a vital component of a compost pile, as well as nitrogen, which comes from food waste, also referred to as “greens.” A balance of 2 to 3 parts “browns” or carbons, to 1 part “greens” or nitrogen is a recommended balance for a successful compost pile.

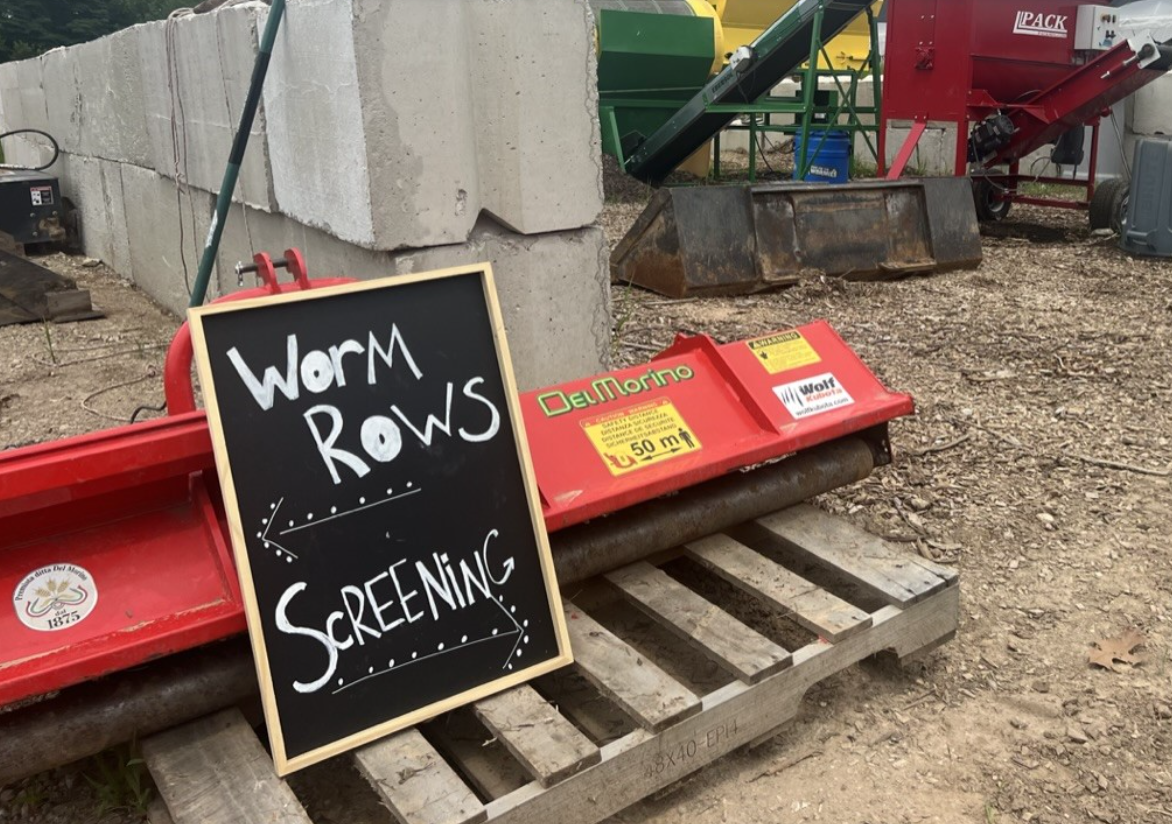

These hot piles will process for about a month, getting turned several times during that initial phase. After a month in this first stage, the compost piles are then spread out into wind rows where they will spend the next year curing and being further processed with the addition of worms. Wormies says that “we have to let the piles cool down to about 80 degrees Fahrenheit before introducing the worms.” This temperature drop allows a hospitable environment for the worms, where they will eat away at any remaining food scraps and start to produce nutrient rich worm castings.

Once the piles have cooled, they introduce what they call their “mother culture”, a combination of finished compost solids sifted from their final product as well as the worms sifted out in the last step. This mother culture is teeming with microscopic life, worm eggs, and mature worms. The worms used in their composting process are the same colony they have been using for over 9 years in fact. The initial batch of worms bought 9 years ago continued to reproduce to such success, that after careful sifting of their final product they can continue to cycle their worms through the compost, batch after batch.

Once the worms have been introduced to the piles, they continue to break down any remaining food particles, leaving behind rich worm castings. This next stage occurs over another 10 to 13 months, giving plenty of time for the compost to cure and regain vital microbiological life. At this final stage before sifting, the compost becomes present with mycorrhizal fungi, protozoa, and the worms that will continue to reproduce in this habitable environment.

To ensure the quality of their product, Wormies sends compost samples to Logan Labs for nutrient value assessments as well as reports on the beneficial bacteria present. After the worm curing stage of 10 to 13 months is complete, the product is sifted twice to ensure no worms or large solids remain in the final product, which is then bagged and brought to their subscribers. The solids sifted out, along with the worm colony and its eggs, are added back into their curing compost as their “mother culture," says Wormies.

The benefits to the community include not only providing a high-quality product of nutrient rich soil amendments to the Kent County area, but also allowing others to compost when they may not be able to do so at their own home. There are a variety of setbacks that may prevent someone from composting at home, such as being on a rental property, an HOA that does not allow it, physical limitations or simply not having a yard to make a compost pile in. Services like Wormies allows communities expanded access to composting. Community composting businesses play an important role in sustainable waste management practices that protect our environment. Composting is a viable and sustainable option for waste diversion, as well as environmental improvement. Not only can composting help local communities by diverting food waste away from landfills where it would release harmful greenhouse gases like methane, but compost can benefit our soil too. According to the United States Compost Council (USCC), the benefits of compost in our soils include improving soils texture and ability to retain water, prevent erosion, store excess carbon, provide nutrients and beneficial microbes to the soil microbiome, as well as provide a better growing environment for plants of all kinds. Compost is a tool for greener futures, and Michigan’s communities are embracing it as a part of their culture.

If you would like to have your own soils tested for nutrient value, visit https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/soil-testing-returns-through-msu-extension for information on testing soils through MSU Extension. For more information about Wormies, visit thewormies.com or email info@thewormies.com. For more information on how to start composting at home, check out MSU Extension’s Master Composter Class. This free, self-led virtual course includes vermicomposting as well as other composting methods. You can also reach out to Compost Systems Educator Eliza Hensel with compost questions at hensele1@msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email