Continuous corn in Michigan: Popular practice, but is it sustainable?

Many Michigan livestock and dairy producers rely on corn-on-corn cropping systems to meet feed demands, but is this short rotation approach truly effective? Here are some considerations for corn-on-corn production systems before sticking with it.

Spring is an exciting and busy time of year on Michigan farms, with field prep and planting in full swing. One common practice observed during this season, especially among livestock and dairy operations, is corn-on-corn rotations, also called continuous corn. Planting corn in the same field each year helps producers meet high feed demands, typically in the form of corn silage. However, managing continuous corn has its challenges, such as nutrient management, residue management and disease pressure. In order to add diversity into the rotation and protect soil with living roots through winter, some farmers plant a cereal rye cover crop following corn harvest in continuous corn systems. The rye will establish in the fall, survive winter dormancy, and will be terminated before planting corn again in the spring.

While continuous corn with cereal rye offers benefits to a livestock producer in terms of feed supplementation, it does not fully replace the advantages of a longer, diversified crop rotation. Additionally, with high input costs and the potential for a yield reduction, the long-term profitability of the operation could be affected.

The importance of a crop rotation

Crop rotations are a fundamental strategy for sustaining productive and profitable farming systems. By alternating different types of crops over time, farmers can manage soil nutrients more effectively. Crop rotations disrupt pest and disease cycles, suppresses weeds, maintain soil structure, and uses soil fertility more efficiently. Corn-on-corn systems, by contrast, are limited in these benefits due to the short nature of the rotation itself. Growing the same crop year after year can lead to nutrient depletion, in particular nitrogen, which is critical for successful corn production. These systems can also allow a buildup of persistent insect and pathogen populations. Over time, this puts added stress on soil and demands more inputs to maintain yields.

Managing continuous corn

Yields in continuous corn are often lower than corn yields in corn-soybean or corn-soybean-wheat rotation. The yield reductions in continuous corn are largely driven by the cumulative effects of nutrient stress, less-than-ideal soil conditions at planting from residue, and disease pressure.

Nutrient management

A cropping system like corn-on-corn will require careful nutrient management, especially nitrogen. Corn is a heavy feeder of nitrogen, and adequate levels of nitrogen must be available at the right time for optimal uptake and performance of the crop. In corn-on-corn systems, this means using starter fertilizer, considering the use of nitrogen stabilizers, and applying a side-dress application during key growth stages of the crop.

Relying on manure from livestock operations helps, but manure alone often doesn’t meet the full nutrient demands of continuous corn. Its nutrient release is slower and less predictable compared to commercial fertilizers, which means timing and availability can be challenging.

Residue management

Another issue is corn residue. Corn leaves behind a large amount of plant material that can keep soils cooler and wetter in the spring. This is especially true in Michigan due to our northern climate. These conditions aren’t ideal for corn seedlings and can slow germination, encourage disease, and increase pest pressure. While a cereal rye cover crop helps manage some of this excess moisture, its benefits may not be enough to offset the downsides of planting corn into high corn residue, especially during cold, wet Michigan springs.

Disease management

In continuous corn, disease management is very important because there is no crop rotation to help mitigate disease pressure issues. Corn diseases survive on plant material left in the field. With greater amounts of residue, there are greater amounts of pathogens, which can increase disease pressure. Corn fungal disease such as northern corn leaf blight, gray leaf spot and tar spot can increase and have greater prevalence in continuous corn. The reliance on fungicides to control heavier disease pressure can create economic pressure on a farm’s profitability through the requirement of greater inputs to produce the crop.

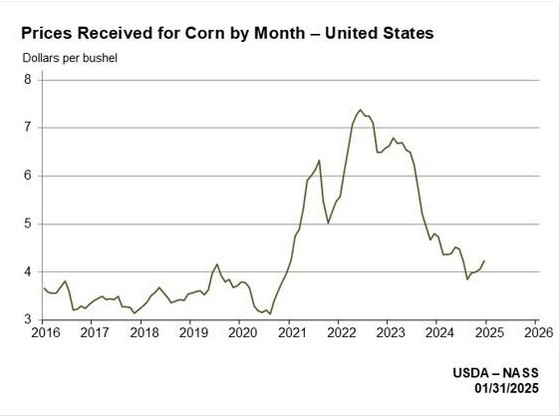

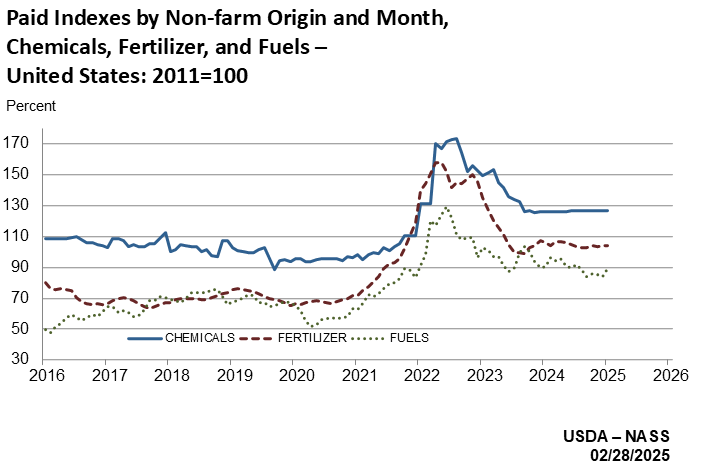

Economic pressures and yield risks

To mitigate the yield reductions driven by a short rotation, continuous corn management relies more extensively on inputs. High fertilizer and chemical costs, coupled with lower corn grain prices, contributes to the high costs of maintaining productivity in a corn-on-corn system and can strain a farm’s bottom line. In today’s market, producers need to weigh these costs carefully. The economic value of raising your own feed may be offset by reduced yields and increased input expenses.

Strategic alternatives

Managing a corn-on-corn rotation successfully is possible, but it requires a high level of attention to detail and willingness to adapt. Field scouting becomes even more critical in these systems to respond early to nutrient deficiencies, weed outbreaks, pest infestations and diseases. Where possible, consider extending your rotations by incorporating other crops such as alfalfa, rye silage or other cash crops like soybean or wheat to reduce long-term pressure on soil and improve overall cropping system performance. Rotating out of corn for even a single season can give fields a much-needed rest, restoring balance to soil nutrients and microbes in the soil.

For operations focused on livestock feed, exploring alternative ingredients may also reduce reliance on corn. Michigan State University Extension offers guidance in this area, including the article, “Using alternative feed ingredients in the dairy cow diet.”

The role of a cereal rye cover crop

Adding a cover crop can offer some crop rotation diversity to continuous corn. Cereal rye is one of the most popular cover crops in Michigan and is widely utilized by farmers in corn-on-corn production systems. This is largely due to its adaptability and resilience in cool climates like Michigan. There are a few shining benefits to using cereal rye in cropping systems in Michigan. First, it can be planted later in the fall, which makes it a practical choice for farmers dealing with busy harvest schedules. The hardy cover crop is also excellent at reducing erosion by protecting soil from harsh winter weather and wet spring conditions. It also manages soil moisture very well by taking up excess water in wet springs, then preserving soil moisture later in the growing season. In the spring, rye’s quick growth allows it to scavenge for leftover nitrogen in the soil, potentially holding up to 100 pounds of nitrogen per acre in its biomass.

Additionally, cereal rye contributes to improved soil structure through its fibrous root system. This root system can reduce compaction and improve water infiltration to the soil, which is an important benefit for fields in which ruts remain from wet harvest conditions the season prior. While cereal rye is a valuable tool in a producer’s crop arsenal, it still doesn’t solve all the issues associated with a short rotation like corn-on-corn.

Cereal rye and feed value

Producers can also consider letting the cereal rye mature into spring and harvesting the cereal rye as feed instead of terminating the crop to plant corn. In Michigan, this usually falls somewhere in mid-May. This makes effective use of one of the benefits of cereal rye in spring—large amounts of biomass. Like most haylage, there is going to be a tradeoff between yield maximization and feed quality, so cutting prior to boot stage is important. Cereal rye yield tonnage will increase as you let it mature, but feed quality and palatability will decrease. A cash crop like soybeans can then be planted following rye harvest. This would achieve the goal of extending a crop rotation where corn could be planted the following year after soybeans.

One important consideration when planting corn or soybeans following cereal rye is timing. You should target the termination of cereal rye 10-14 days prior to planting a cash crop like corn or soybean due to potential yield losses. For more information on when to terminate cereal rye, refer to the article, “Terminating cereal rye to prevent yield loss in corn and soybeans.”

Michigan State University Extension has additional information on cover crops that can be found on the cover crop website and in a bulletin on cereal rye.

Final thoughts

While corn-on-corn can help meet feed demands, it does not come without tradeoffs. Managing this system well will require diligent nutrient planning, strategic residue management, and a keen eye on both economic and agronomic indicators. Incorporating longer rotations and adding additional crop diversity remains the most effective strategy for improving soil health, reducing input costs, and sustaining farm profitability over time. For many producers, the most profitable long-term decision may be to give corn-on-corn fields an occasional break.

Print

Print Email

Email