Cool, fall nights challenge fruit storability

The cool, clear nights of Sept. 18 and 19, 2020, could result in chilling injury to Honeycrisp apples.

The highly desirable Honeycrisp apple is also one of the most tender apples we grow. It has an extreme sensitivity to low temperature that we usually see after harvest following some weeks of cold storage. However, if the temperatures in the orchard are low enough, we can have fruit injury even before growers have a chance to harvest the fruit (Photo 1).

There are numerous anecdotal reports that low temperatures in the orchard can cause chilling disorders before harvest. This year, we had a couple days of low nighttime temperatures in the orchard across most of Michigan. On Sept. 18, 2020, the skies were clear and the National Weather Service predicted temperatures in the 30s and a high probability of our first frost of the year. At this point of the season, most of the Honeycrisp crop is still in the orchard and fruit just beginning to ripen. On an average year in the Grand Rapids, Michigan, area, Honeycrisp are usually ready for harvest and storage by Sept. 15. Unfortunately, a ripening Honeycrisp is more susceptible to chilling injury. After harvest, storage operators in Michigan reduce the risk of chilling injury by holding Honeycrisp for five to seven days at 50 degrees Fahrenheit or so in a process known as conditioning.

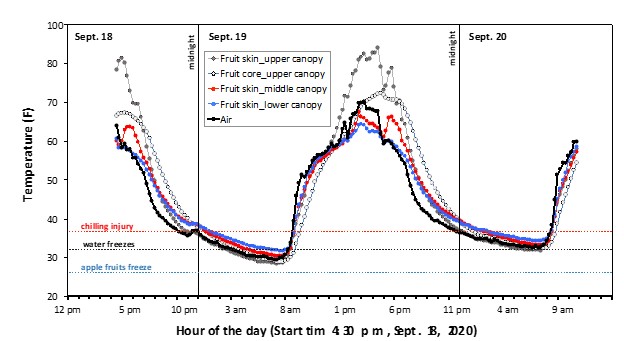

To better understand how nighttime air and fruit temperatures changed during the predicted frost event, Michigan State University Extension personnel instrumented a Honeycrisp apple tree at a commercial orchard north of Grand Rapids. Thermocouples were either placed in the air 3 feet above the ground or were embedded into fruit. Fruit temperatures were collected for fruit at the top of the canopy (8 feet above ground), at the middle of the canopy (5 feet above ground) and at the base of the canopy (2 feet above ground). Thermocouples were placed just under the skin of the fruit to collect fruit surface temperatures. For the fruit at the top of the tree, we also inserted a thermocouple into the fruit core to track inner fruit temperature.

The expectation was that the fruit at the top of the tree would be warmest during the day, but would cool to the lowest temperatures at night as they lost heat to the clear night sky. The question was how cool they would get relative to the night air. We found that those fruit at the top of the tree cooled to lower temperatures than those fruit in the middle or at the bottom of the canopy (Photo 2). In fact, these fruit cooled to temperatures 1 or 2 degrees below air temperatures due to radiation cooling.

The air temperature dropped below the temperature known to cause chilling injury in Honeycrisp for about 8 to 10 hours on the night of Sept. 18 and about 6 hours on the night of Sept. 19. More importantly, the temperatures of the fruit skin and core dropped below freezing for about 4 to 6 hours on Sept. 18. While apple tissue does not freeze until it is cooled to about 26 F, the extreme low temperatures are a worry for this sensitive variety. This low temperature shock may be enough to induce chilling injury.

To see if the affected fruit would develop injury, fruit were collected before and after the chilling event. Those fruit are in storage now; we'll know if any damage occurred after about three weeks of cold storage. Our findings will help inform our apple fruit industry as to the risks of these unusual early autumn frost events. In the meantime, we would urge our storage operators to be vigilant for developing symptoms of chilling injury on Honeycrisp harvested Sept. 19 and later.

Print

Print Email

Email