Cover crops Part 1: Valuable cultural component of your organic weed management toolkit

When applied correctly, cover cropping can have benefits beyond soil health.

This article is part one of a two-part series. This first installment highlights how cover crops can suppress weeds by diversifying and filling gaps in a crop rotation and by competing with weeds for light, nutrients and moisture. The second article will address how some cover crops release chemicals that inhibit the germination and growth of weeds (allelopathy), while others attract beneficial organisms that feed on weeds and weed seed.

Cover crops are crops grown between harvest and planting of commodity or feed crops, usually not for harvest, but used instead for the production of biomass and the various agroecological benefits this additional biomass can provide. While cover crops are most often thought of as a means of preventing erosion and improving soil health, they can also be applied as an effective weed management tool. The ability of cover crops to suppress weeds is especially valuable in organic production systems where restriction of synthetic herbicide use leaves growers without any simple weed control solutions. Organic weed management can be so challenging, in fact, that organic farmers frequently cite weeds as the greatest barrier to organic production.

Cover crops can suppress weeds in four primary ways:

- Diversifying and filling gaps in a crop rotation.

- Competing with weeds for light, nutrients and moisture.

- Releasing chemicals that inhibit the germination and growth of weeds (allelopathy).

- Attracting beneficial organisms that feed on weeds and weed seed.

The following explains how the first two of these suppressive mechanisms function and can be successfully applied.

Diversifying and filling gaps in a crop rotation

Diverse crop rotations suppress weeds by forcing them to grow in different crops with varying lifecycles, growth habits, spatial arrangements and management requirements. Rotating dissimilar crop species also allows the application of a wide range of control measures and exposes weeds to more natural mortality factors. For example, adding a year or two of a perennial legume crop like clover between annual vegetable crops can reduce the germination of annual weeds normally triggered by soil disturbance and also permits regular mowing that can suppress problem perennial weeds like Canada thistle

It is also important to remember that many weeds are pioneer species that tend to establish quickly and thrive in disturbed habitats. Gaps in a crop rotation that leave bare soil exposed create the ideal environment for weed growth. While mechanical control methods like cultivation can knock back weeds for a period of time, any farmer knows that this effect is only temporary. Disturbing the soil essentially resets the successional clock, bringing new weed seed to the soil surface and initiating more weed germination and growth. While it may be possible to till frequently enough to keep weeds down, tillage degrades soil health and tillage equipment is costly to operate.

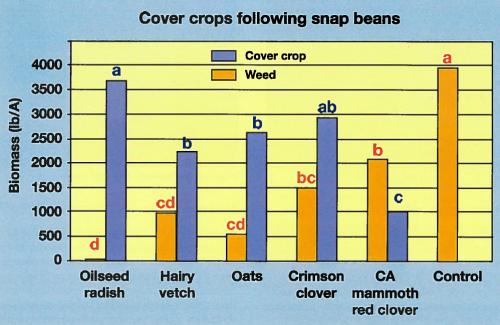

Cover crops can be grown in short windows before and after cash crops to fill gaps in a rotation and minimize the exposure of bare soil. Filling out a crop rotation, keeping fields green year-round, limits the ability of most weeds to germinate and become established. For example, research at MSU’s Kellogg Biological Station found that oilseed radish grown following snap beans reduced weed biomass 98.5 percent compared to plots left bare after beans were harvested (Figure 1). Weeds able to gain a foothold in a growing cover crop will be much less vigorous as they are forced to compete for the necessities of life.

Fig. 1. Cover crops following snap beans suppress weeds. LSD at 0.05 weeds-990, cover crops-1020.

Figure credit: Mutch and Martin, KBS, MSU

Competing with weeds for light, nutrients and moisture

Plants need light, nutrients, moisture and CO2 to survive. The more plants present in a field, the less of each there will be available to go around. A vigorously growing cover crop, whether alone or interplanted with a cash crop, can prevent weeds from germinating and growing to the point that they produce seed or compromise cash crop yields. However, successfully applying this strategy requires knowledge of weed ecology, careful selection of cover crop species and favorable conditions for cover crop establishment and growth.

For example, a 2005 study by Michigan State University Extension specialist Dan Brainard found that sorghum-sudangrass, a tall tropical grass, planted in July following an early season vegetable crop reduced overall weed biomass 91 percent and the seed production of Powell amaranth (pigweed) by 95 percent compared to a bare ground control. However, in the same study, soybean used as a cover crop only reduced weed biomass by 59.3 percent and Powell amaranth seed production by 57 percent.

Why such dramatically different implications for weed control based on cover crop choice? The most basic issue in that comparison was cover crop stature. Sorghum-sudangrass grows quickly in mid-summer to form a full canopy that blocks light from even tall weeds like pigweed. Conversely, soybeans can be slow to establish in dry summer soil and will never grow tall enough to shade rapidly developing pigweed plants. Sorghum-sudangrass is also one of the cover crop species known to produce allelopathic compounds, but more on that later.

Unfortunately, the competitive impact of cover crops is not restricted to weed species. Research has shown that cover crops capable of out-competing weeds will likely also suppress an interplanted cash crop. For example, a 1998 study by Brandsaeter et al. found that a white clover living mulch suppressed both weed and cabbage growth. In the case of living cover crops, cash crop suppression is most often the result of competition for water. Cover crop residues can also negatively impact the establishment of a cash crop. This is usually related to physical interference with seed placement in the soil, prevention of soil warming, tie-up of nitrogen, or the release of allelopathic compounds.

For more information on using cover crops as a weed management tool, view the second article in this series and consider attending the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo Dec. 10th-12 at Devos Place Convention Center in Grand Rapids, Mich. Visit www.glexpo.com for session and registration information.

References

- Grass–Legume Mixtures and Soil Fertility Affect Cover Crop Performance and Weed Seed Production, Dan Brainard et al.

- Yields, Weeds, Pests and Soil Nitrogen in a White Cabbage-Living Mulch System, Brandsaeter et al.

- Third Biennial National Organic Farmer’s Survey, E. Walz

Print

Print Email

Email