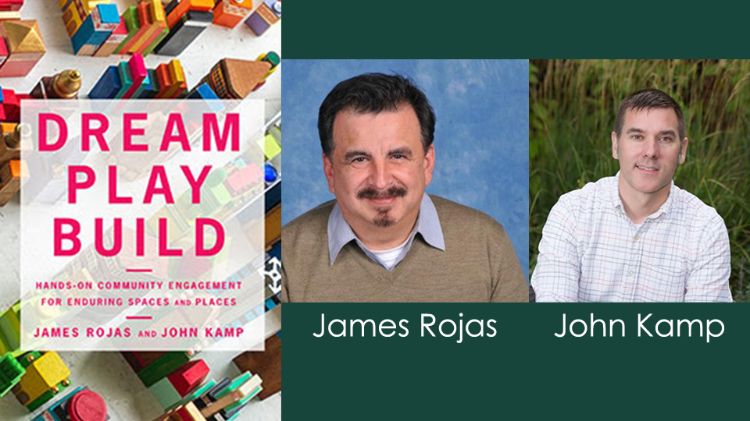

Dream Play Build

James Rojas and John Kamp share their Dream Play Build model.

"Ever since learning about the Dream Play Build methodology, I’ve been wondering about using it before or within a charrette. I think it is a great example of an inclusive technique, however it is used. Our thanks to James Rojas and John Kamp for sharing their process and a project that used it in this month’s article. If you want to know more, get the 'Dream Play Build' book here." - Holly Madill, Director NCI

In the playful, hands-on model-building workshops we do with diverse audiences around the country, we don’t require participants to design at a scale or be perfect, and we never use literal objects when we invite them to build models of both memories and ideal spaces and places.

Absent any concerns about scale, participants can be freer and more expansive in their thinking. And by using non-representational found objects (e.g., pipe cleaners, hair rollers, trinkets, etc.), participants are challenged to think even more creatively: if you are building a memory of water, don’t look for water for your model, find something blue that can stand in for water.

However, we oftentimes get the question of how these less conventional model-building methods and materials can lead to real and tangible change in our cities, towns, and neighborhoods. In our case, our role as facilitators and designers is to not only have participants share back what they have built but also draw connections amongst the models to generate a set of core, recurring themes that can guide the design process.

As an example, we can turn to a current model-building → design → build project we are working on in Oakland, CA, called the Frog Park Climatescape. The project reveals not only how outcomes of the model-building workshops can guide the design of an urban space but also how the workshops serve a deeper, intangible goal: creating group cohesion and deeper community bonds by involving a broad cross-section of folks in the process from start to finish.

In April of last year, we were contacted by the volunteer committee (FROG) that oversees a local Oakland greenspace called the Rockridge-Temescal Greenbelt (typically known just as Frog Park). We were invited to redesign what had once been a rose garden, which had, in a much earlier incarnation, been a decrepit playground.

Unbeknownst to anyone until it was too late, the rose garden’s irrigation system had broken, and all the roses died. Yet, instead of having the city replace the irrigation system and replant the roses, which had never thrived, John proposed the Climatescape approach he has been honing over the past 15 years: a landscape that employs a set of site-prep, planting, and watering techniques so that it does not need irrigation after the first growing season. It is a landscape both anchored in the climate that it is in but also one that responds to climate change.

To kick off this project, generate creative ideas, and ensure as much community participation as possible, we facilitated a model-building workshop with the FROG Board members at the site. For the first workshop activity, we had participants use found objects—blocks, spools, pipe cleaners, curlers— to build their earliest or favorite landscape memory. People’s memories were full of joy, wonder, color, and out of them we generated a set of common themes. One element that struck us about the memories was how people had found joy in very simple experiences: trillium blooming underneath Redwoods, the smell of honeysuckle blooming on the side of a fence, a field of lavender.

For the second activity, people worked in teams to build their ideal Climatescape. Once the teams had finished, they presented their ideal garden space to the group. From there, we established common themes and aspirations for the space. These themes included vertical elements for the space, things to climb on, and seating. The themes from both this and the first activity guided the final design John created for the Climatescape.

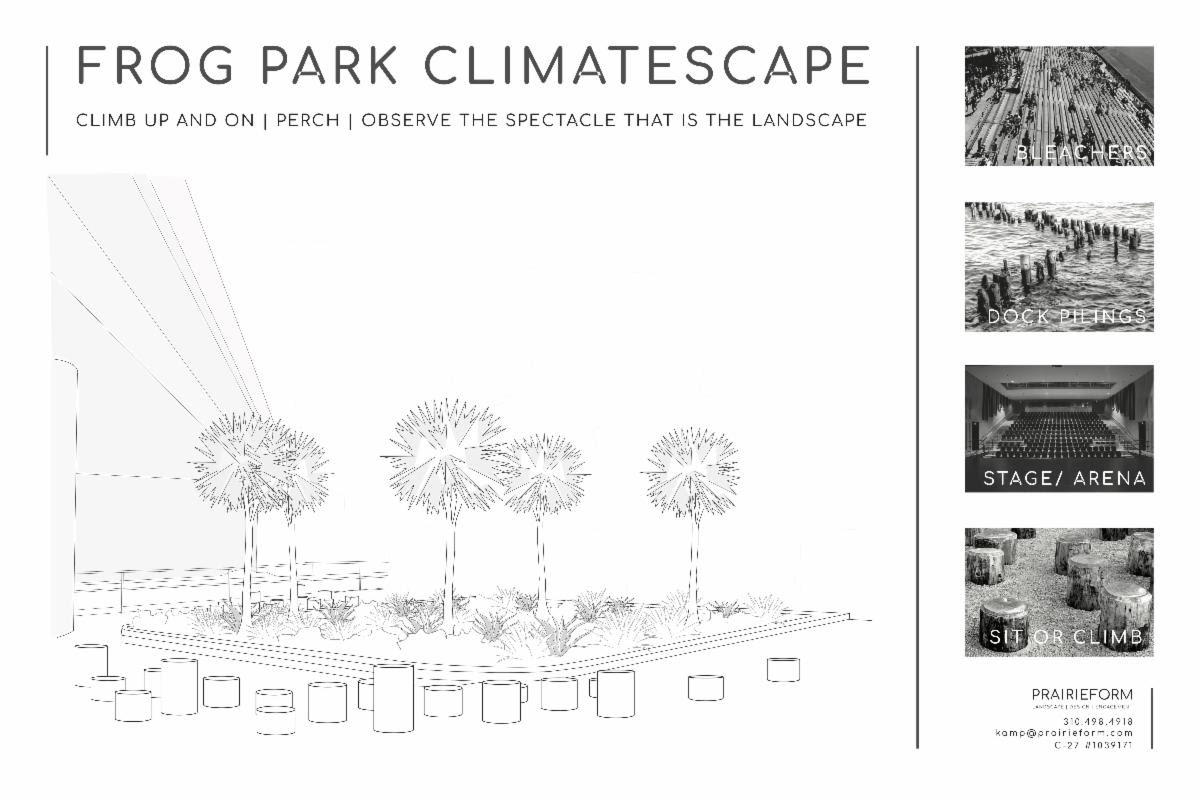

A particular design challenge was how to integrate the ideas of climbing elements and verticals into the space without essentially making a playground where the plants would simply get trampled on. After sketching out initial ideas, John homed in on the idea of treating the garden as a stage, with the landscape as a kind of soft spectacle. Around the landscape but not inside of it would be a set of deconstructed risers that people could climb, play, or perch themselves on at different heights and then from there could observe the quiet spectacle of the landscape. This idea of the quiet spectacle references the simplicity of the landscape memories participants built models of. At the design review meeting, these design components strongly resonated with the workshop participants and will now become an integral feature of the project.

To broaden the reach of the project and involve even more people in it, we crowdsourced some of the plants, and included one of the installation days as part of the Creek to Bay Day, a Bay-Area-Wide watershed improvement, clean-up, and education day. We had over 15 volunteers helping with the site prep. The extra people-power came in extremely handy, as we ended up discovering a layer of asphalt underneath the site and had to jackhammer out 4’ diameter holes in a honeycomb grid across the space. When we moved on to the planting phase, neighbors volunteered to help out as well, thereby expanding the community reach of the project even further.

In the end, the model-building workshop and the subsequent project installation activities that followed have served as both a creative launching pad for the project and a community strengthener. The ideas of the deconstructed risers and the landscape as a stage for a quiet spectacle to unfold came about because of the model-building activities we did with the community. Additionally, the workshop and subsequent installation activities have brought a cross-section of community into the fold that might not have been involved otherwise—including those of a range of ages and those with no design experience whatsoever.

This broad community involvement and buy-in will invariably help as we move into the Phase 2 of the project, which includes the installation of the deconstructed risers and interpretive signage, and the necessary fundraising to make this portion of the project possible. Once completed, participants at all stages of the project will be able to explore, inhabit, and hang out in the spaces and elements they have literally had a hand in in creating.

This experience is our first complete model-building to design to build project. Usually, we guide only part of the process, not all parts from developing themes to construction. But we had long been wanting to carry a project through from start to finish, showing how the Place It! Model-building workshop can be an effective tool for not only generating creative ideas for a design but also involving communities in meaningful ways in the process. Additionally, participants can feel a sense of accomplishment when they see and can experience the physical manifestation of our ideas.

Print

Print Email

Email