Irrigation management to reduce cost and foliar disease

Understanding the disease triangle, water management and leaf wetness influence on foliar disease, when to apply a fungicide, and a review of what we’ve learned so far on how to best manage tar spot.

A number of foliar diseases can impact corn production in Indiana and Michigan, including gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight and now tar spot. Environmental conditions, particularly moisture, during the growing season will play a big role in the risk of foliar disease development in a field. Irrigation can confound this. Therefore, we want to review some of the factors to consider when making disease management decisions. These include understanding the disease triangle, water management and leaf wetness influence on foliar disease, when to apply a fungicide, and a review of what we’ve learned so far on how to best manage tar spot.

Disease triangle

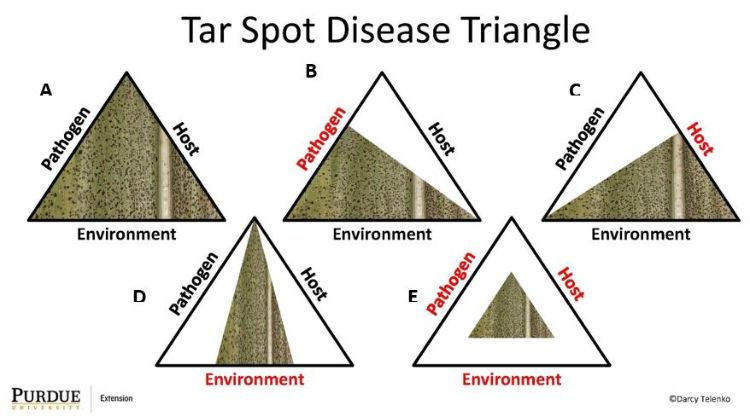

There are three parts to the disease triangle that influence the amount of disease that will develop in a crop canopy: the presence of a 1) virulent pathogen, 2) susceptible host and 3) favorable environmental conditions (Figure 1A). Each plant disease has its own set of individualized factors that contribute to the disease triangle and determine the risk and impact on yield. For example, with tar spot of corn, the pathogen Phyllachora maydis may either overwinter on diseased tissue (pathogen is present in a field) or move with weather systems.

Figure 1 gives an example of how if the pathogen, host or environment factor becomes unfavorable then the amount of disease that will develop is decreased. Factors such as reduced initial inoculum (Figure 1B), host resistance (Figure 1C) or lack of leaf moisture (environment) (Figure 1D) all can lead to the decreased risk of foliar diseases. If one or more factors are combined, risk can further be decreased (Figure 1E).

Water management and leaf wetness

Leaf wetness is a major driver of disease development. Fungal diseases require moisture to produce spores and to infect the plant. Differences between years in rainfall patterns often drive disease onset and severity. For example, most of the great lakes region saw regular rainfall during the 2018 growing season this resulted in early onset of tar spot and a significant epidemic. Compare that with 2019, which saw a much slower onset and buildup of tar spot, due in large part to the dry late July and August that was experienced in the region.

Irrigation obviously provides additional leaf wetness events that can drive diseases including tar spot. In 2018, we had multiple accounts of irrigation contributing to disease development and driving 50 bushel per acre yield losses as compared to non-irrigated sections. Conversely, we had an interesting example in 2019, where it was clear that irrigation was driving tar spot disease, however due to the much drier growing season, irrigation was necessary to maximize yield potential.

In addition, we have several anecdotes of frequent light irrigation events driving tar spot development. Try to minimize leaf wetness by avoiding frequent light irrigation and watering appropriately. Work is also currently being conducted to examine the impact of the timing of irrigation and how this might be manipulated to minimize leaf wetness. For example, to maximize disease pressure in our fungicide disease screening trials, we may irrigate in the early evening hours to try and promote a prolonged leaf wetness throughout the night.

Decision making for applying a fungicide

Fungicides are a great tool to have in your disease management toolbox. They can be effective at reducing disease and protecting yield, but there are a number of factors that should be considered before pulling the trigger.

- Disease risk in the field. Is there a history of a particular disease causing a problem? What was the previous crop?

- Current disease activity. While scouting, is the disease active in the lower canopy? Is there indications that the disease is spreading (example, Southern Corn Rust Tracking Map).

- Weather conditions. Will there be favorable environmental conditions for the disease to continue to develop? Is there a lot of rain and moisture to encourage many of our foliar diseases? Are there tools that can help predict risk?

- Return on investment. Will the yield protected by a fungicide cover additional costs of the application?

You’ve made the decision to apply a fungicide—now what?

The Corn Disease Working Group has developed ratings for how well fungicides control major diseases of corn in the United States. This table is annually updated based on field testing of products. We pulled some of the information for reference in Table 1. The full document is found in the resources section on the Crop Protection Network website. We highly recommend leaving check strips to determine your ROI from fungicide applications; the results might be surprising.

Managing tar spot

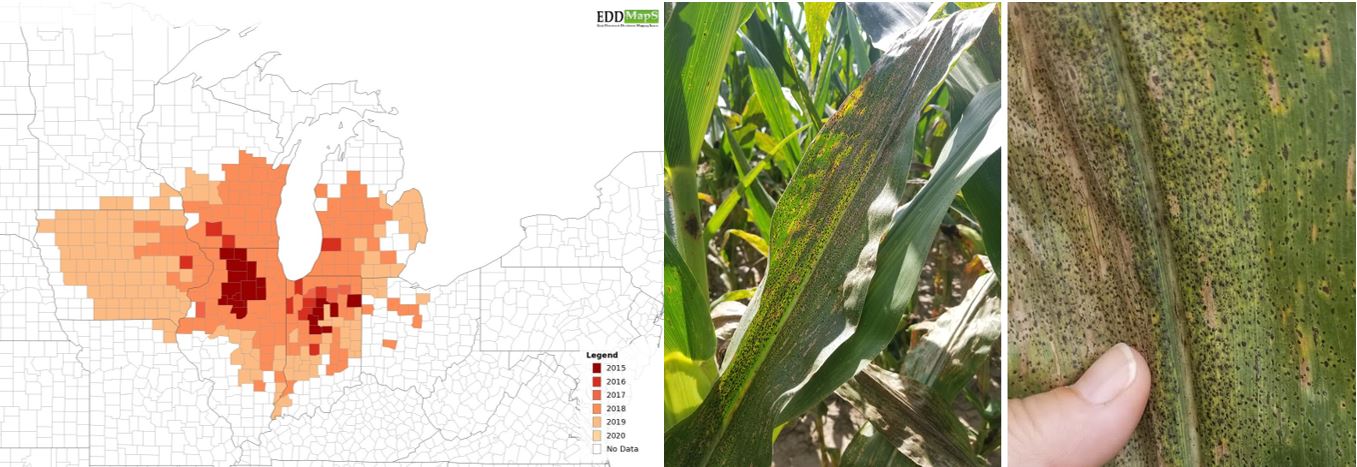

Tar spot is a disease of corn previously reported in Central and Latin America. In 2015. tar spot was found for the first time in the U.S. in the states of Indiana and Illinois. Since then, a significant epidemic was observed in 2018 with continued spread in 2019. The disease has now been confirmed in nine states including Florida.

As the name suggests, the disease appears and feels like flecks of black tar on the leaves, which cannot be rubbed off the leaf. These small (1/16 inch), black spots are the fungal fruiting structure, which are capable of releasing spores to infect new corn plants. The fungus Phyllachora maydis is the only pathogen associated with this disease that has been confirmed in the U.S. In Mexico, an additional fungal species is suspected of causing fish-eye symptoms, which is seen as dead leaf material around the black spots. We see the fish-eye symptoms in the U.S., however, to date we have not found any secondary species associated with these symptoms. In fields with severe disease, the corn will often appear frosted, will senesce early and may lodge.

Aside from the impact on grain yield and test weight, we have also observed the impact of this disease on silage quality. When severe the disease results in corn that is too dry for silage production, and it reduces silage quality by reducing the digestible component and energy value of the feed. Thankfully, there are no associated mycotoxins with this disease. A challenging aspect of tar spot is the rapid progression of disease. In some fields the first signs of disease were observed in early July, with widespread symptoms at the start of August that led to complete senescence at the field level by early September.

As with the management of any disease, selecting hybrids with good disease resistance packages is essential. However, as tar spot is so new to North America, none of our material has previously been screened and bred for this disease. An assessment was made on the impact of tar spot on corn hybrids, which can be found in “How Tar Spot of Corn Impacted Hybrid Yields During the 2018 Midwest Epidemic.” It was found that no hybrids were immune; however, there were differences with some hybrids being more resistant than others. With every 10% increase in tar spot severity, we noted a 5 bushel per acre yield loss. Additional screening of hybrids and inbreds will be necessary to identify and incorporate sources of resistance into available hybrid varieties.

Talk to your seed salespeople for any updates. With little information, it would be best to spread risk by planting a few different hybrids. Planting corn on corn may increase the risk of developing tar spot, however even fields under a soybean-corn rotation have been significantly impacted, most likely as the spores are readily dispersed on the wind and capable of moving some significant distance.

Although fungicides help in managing tar spot, do not expect 100% control. Fungicide timing is critical for maximizing tar spot disease management. At this point, we will have to see what weather conditions and disease pressure is like in 2020. The pathogen is capable of overwintering on infested residue, so in areas where the disease is becoming established there will be a greater availability of disease inoculum to initiate disease. Scouting fields will be essential to stay ahead of this disease. In some situations, it may make economic sense to make two fungicide applications or possibly hold that VT/R1 application to slightly later in the season. We are working with collaborators to develop fungicide spray forecasting models.

In order to track tar spot this coming season, we would like to hear from you. Especially if you observe tar spot in counties that have not been confirmed to date, please send a picture of diseased leaves to us directly at email: chilvers@msu.edu, dtelenko@purdue.edu or Twitter: @MartinChilvers1, @DTelenko.

For more information on tar spot and other diseases, visit the Crop Protection Network website.

|

Table 1. Fungicide efficacy for gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight, southern rust and tar spot. Adapted from Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Corn Diseases, CPN-2011-W. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Class |

Active ingredient (%) |

Trade name |

Rate/A (fl. oz) |

Gray leaf spot |

Northern corn leaf blight |

Southern rust |

Tar spot1 |

Harvest restrictions2 |

|

QoI Strobilurins Group 11 |

azoxystrobin 22.9% |

Quadris 2.08SC multiple generics |

6.0-15.5 |

E |

G |

VG |

NL |

7 days |

|

pyraclostrobin 23.6% |

Headline 2.09EC/SC |

6.0-12.0 |

E |

VG |

VG |

NL |

7 days |

|

|

picoxystrobin 22.5% |

Aproach 2.08SC |

3.0-12.0 |

F-VG |

VG |

G |

NL |

7 days |

|

|

DMI Triazoles Group 3 |

propiconazole 41.8% |

Tilt 3.6EC multiple generics |

2.0-4.0 |

G |

G |

F |

NL |

30 days |

|

prothioconazole 41.0% |

Proline 480SC |

5.7 |

U |

VG |

G |

NL |

14 days |

|

|

tebuconazole 38.7% |

Folicur 3.6F multiple generics |

4.0-6.0 |

U |

VG |

F |

NL |

36 days |

|

|

tetraconazole 20.5% |

Domark 230ME |

4.0-6.0 |

E |

VG |

G |

NL |

R3 (milk) |

|

|

Mixed Modes of Action |

Azoxystrobin 13.5% propiconazole 11.7% |

Quilt Xcel 2.2SE multiple generics |

10.5-14.0 |

E |

VG |

VG |

G-VG |

30 days |

|

benzovindiflupyr 2.9% azoxystrobin 10.5% propiconazole 11.9% |

Trivapro 2.21SE |

13.7 |

E |

VG |

E |

G-VG |

30 days |

|

|

cyproconazole 7.17% picoxystrobin 17.94% |

Aproach Prima 2.34SC |

3.4-6.8 |

E |

VG |

G |

G-VG |

30 days |

|

|

flutriafol 19.3 % fluoxastrobin 14.84% |

Fortix 3.22SC Preemptor 3.22SC |

4.0 -6.0 |

E |

VG-E |

VG |

NL |

R4 (dough) |

|

|

flutriafol 26.47% bixafen 15.55% |

Lucento |

3.0-5.5 |

VG-E |

VG |

VG |

G-VG |

R4 |

|

|

prothioconazole 16.0% trifloxystrobin 13.7% |

Delaro 325SC |

8.0-12.0 |

E |

VG |

VG |

G-VG |

14 days |

|

|

pydiflumetofen 7.0% azoxystrobin 9.3% propiconazole 11.6% |

Miravis Neo 2.5SE |

13.7 |

E |

VG-E |

VG |

G-VG |

30 days |

|

|

pyraclostrobin 28.58% fluxapyroxad 14.33% |

Priaxor 4.17SC |

4.0-8.0 |

VG |

VG-E |

VG |

U |

21 days |

|

|

pyraclostrobin 13.6% metconazole 5.1% |

Headline AMP 1.68SC |

10.0-14.4 |

E |

VG |

G |

G-VG |

20 days |

|

|

trifloxystrobin 32.3% prothioconazole 10.8% |

Stratego YLD 4.18SC |

4.0-5.0 |

E |

VG |

G |

NL |

14 days |

|

|

tetraconazole 7.48% azoxystrobin 9.35% |

Affiance 1.5SC |

10.0-14.0 |

G-VG |

G-VG |

G |

G |

7 days |

|

|

Flutriafol 18.63% Azoxystrobin 25.30% |

TopGuard EQ |

5.0-7.0 |

VG |

G |

U |

G-VG |

45 days |

|

|

Mefentrifluconazole 17.56% Pyraclostrobin 17.56% |

Veltyma |

7.0-10.0 |

VG-E |

VG-E |

VG |

G-VG |

21 days |

|

|

Mefentrifluconazole 11.61% Pyraclostrobin 15.49% Fluxapyroxad 7.74% |

Revytek |

8.0-15.0 |

VG-E |

VG-E |

VG |

G-VG |

21 days |

|

1 Fungicide application timing is extremely important and needs to be made near the onset of the tar spot symptoms. Efficacy ratings based on limited site locations from 2018 and 2019. A 2ee label is available for several fungicides for control of tar spot, however, efficacy data are limited. Check 2ee labels carefully, as not all products have 2ee labels in all states.

2 Harvest restrictions are listed for field corn harvested for grain. Restrictions may vary for other types of corn (sweet, seed, or popcorn, etc.), and corn for other uses such as forage or fodder. This information is provided only as a guide. It is the applicator’s legal responsibility to read and follow all current label directions. Reference in this publication to any specific commercial product is for general information only, and does not constitute an endorsement or recommendation by the CDWG. Individuals using such products assume responsibility for their use in accordance with current directions of the manufacturer. Members or participants in the CDWG assume no liability resulting from the use of these products.

Print

Print Email

Email