Is it natural genetic variation or genetic modification?

There is far more variety in our food items than what we observe. When we see something different than what we are used to, don’t assume it has been genetically modified.

With the development and introduction of genetically modified (GM) crops into our food system, consumers are often left wondering “What is GM and what is not GM?” This is especially complicated since most consumers are unaware of the great variation naturally occurring within plant and animal systems. I like to use the analogy that what most of us see and experience in our food options is only an inch on a yardstick.

Why do we only see an inch? The average grocery store now carries 40,000 to 50,000 items—incredible! Just 20 years ago, it was 7,000. Fruit, vegetables, meat and dairy require expensive space since most are refrigerated or frozen, requiring a rapid turnover since they are highly perishable. Due to these requirements and space restrictions, supermarkets must offer what will sell in a reasonably short time. That is why you only see green, red and purple grapes that generally taste the same—sweet. We buy these based more on color than flavor; however, the flavor range in grapes is incredible and that presents a problem. If a stronger flavor comes into play, consumers can either like it or not like it. It is hard to object to sweet, and there simply is not enough space to display everything.

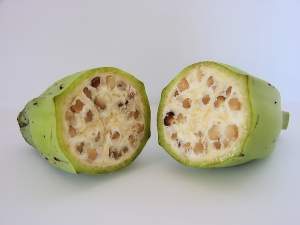

Photo 1 shows a small portion of the diversity within potatoes (there are over 4,000 varieties). Few resemble what is available in a supermarket, but they are all naturally occurring—no genetic modification. They will also all intercross, allowing potato breeders to move color, shape, flavor, texture, disease resistance and other traits from one variety to the next. The U.S. market demands a round or oblong, smooth potato—no bumps or ridges. Why? Bumps and ridges are hard to peel.

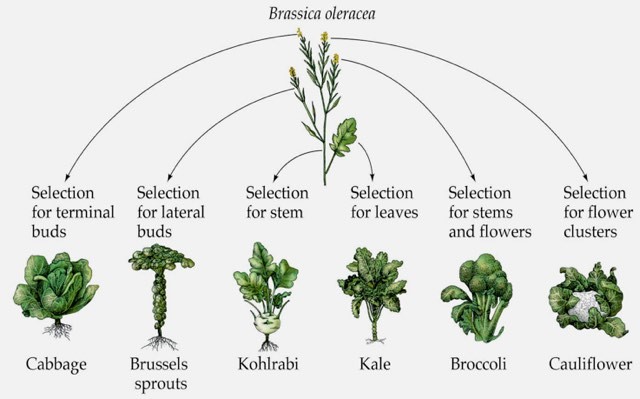

Another good example is what humans, through natural selection, have done with wild mustard. Wild mustard is an annual weed with yellow flowers. It is native to Europe and East Asia but now found wild around much of the world. However, it has given rise to many of our better-known vegetable crops (Photo 2). The six crops shown in Photo 2 are all the same plant, just taken in a different direction utilizing the natural genetic diversity present within wild mustard. Modern genetic engineering techniques were not used to develop these plants having such a great difference in appearance.

Probably the best example of all in how humans have manipulated and utilized naturally existing genetic diversity is in our best friends, dogs. The range in size, shape, color, speed, strength, temperament and other traits in dogs is huge, but they are all the same species. They all can interbreed and exchange genetic material. Overtime we have just selected traits that at first, we found useful as working or hunting animals.

The next time you see 2-inch long blackberries, quarter-size blueberries, thumb-size raspberries, strawberries as big as your fist and multicolored carrots or beets, that is just an expression of the natural genetic variation existing within that plant we are utilizing to improve nutritional components, flavor or make them more visibly appealing. No genetic engineering has gone on to produce these sizes or colors—it was already built in!

The next time you see 2-inch long blackberries, quarter-size blueberries, thumb-size raspberries, strawberries as big as your fist and multicolored carrots or beets, that is just an expression of the natural genetic variation existing within that plant we are utilizing to improve nutritional components, flavor or make them more visibly appealing. No genetic engineering has gone on to produce these sizes or colors—it was already built in!

Final thought: Seedless watermelon are not genetically engineered but are obtained through doubling chromosomes using a naturally occurring chemical.

Print

Print Email

Email