Local government strategies to protect groundwater

Groundwater can, and in some places has already, become contaminated. Local government is best-suited to prevent contamination from occurring with straightforward planning and zoning tools at their disposal.

Protecting groundwater supplies is often unaddressed until it is too late. Keep your community’s water supply clean and safe with some common sense approaches in your master plan, zoning ordinance, and other community practices:

Develop a wellhead protection plan if your community has a type I public water wells/public water system. A Wellhead Protection Program is designed for public water supplies. With Wellhead Protection, communities conduct a detailed study about its water wells including the area from where the well pulls its groundwater. To do this, hydrologists trace the route of the water backward for ten years and draw a map showing the land surface corresponding to the area above ground where the water originated. This map delineates the critical land area where actions on the surface can result in contamination getting into the ground and eventually making its way into the public water supply. The community writes a Wellhead Protection Plan for each municipal well or well system. The plan includes a historical inventory of what land uses occurred in the past that might have contributed contamination so the community can be proactive about looking for that contamination. The plan also inventories current land uses and finally the plan describes steps they will take to avoid contamination sources in that area in the future.

Use an overlay zone for even more protection around municipal water wells (type I water wells). This will protect the water that would be pumped into a public water well during the ten-year, five-year, and one-year time of travel. More on this is found in the Land Use Series “Sample Zoning Amendments and Program For Groundwater Protection.” Zoning should prohibit certain land uses (known as high-risk contamination sources) within the overlay district. It should also include site plan review standards that include secondary containment design where hazardous substances are stored, handled, or used. “Secondary containment” is a design approach that recognizes accidents, such as spills, happen, but the space is designed so any spill is contained and does not soak into the ground. That means no drains, swales, ditches, or other systems that discharge onto the ground.

Draft and include zoning amendments for general groundwater protection. The sample zoning for groundwater protection, mentioned above, includes other sample language for zoning ordinances. For example, “wall-to-wall” protection that requires site plan review with secondary containment standards to protect not only municipal water wells but also private water wells, surface water, and wetlands.

In addition, there needs to be provisions in zoning concerning surface water (including wetland) protection. The article "Local government has an important role for water quality protection" talks about this local government role. Part two presents a perspective of retaining important habitat on lake and river edges and part three discusses the legal aspects. There is also a guidebook which suggests planning and zoning essentials to protecting water quality. That book includes six essential elements in master plans and zoning ordinances can help protect Michigan’s water quality. The water quality protection guidebook can help rural communities understand and include those provisions in their plans and regulations.

Local governments can also adopt police power ordinances, and other programs to avoid contamination such as fire chief inspections, incentives, and education campaigns.

Why might you want to bring these practices to your community? Three practical reasons: drinking water supplies, businesses, and ecosystem dependence. Also hunting, fishing, tourism and aesthetic benefits flow from unpolluted fresh water.

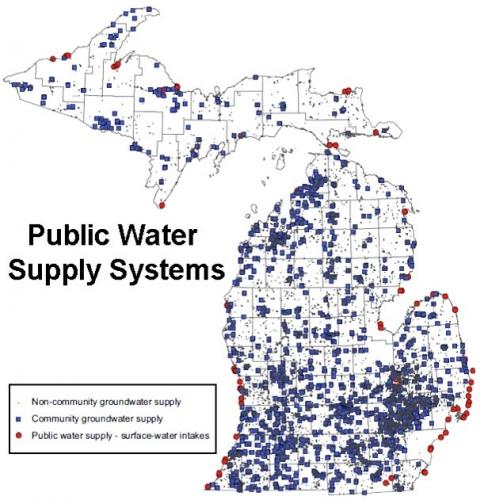

In Michigan, groundwater is the source of drinking water for 45 percent of the state’s population. Public water supplies using groundwater serve 1.7 million people while 2.6 million people rely on private water wells in groundwater for their water supply (Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy). An interactive story map of drinking water and local options for protection serves as a reference tool for local units of government looking to enact local policies to better protect their drinking water. The project was funded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In addition, groundwater is the major source for agricultural irrigation on 5,153 farms (2017 Census of Agriculture). Groundwater is also critical to many ecosystems in Michigan – providing a steady flow of cool high-quality water to streams, lakes, and wetlands.

Public water systems map, presentation materials by David Lusch, MSU Institute of Water Research.

Despite widespread dependence on groundwater, zoning tools to protect or prevent contamination of groundwater are less widespread.

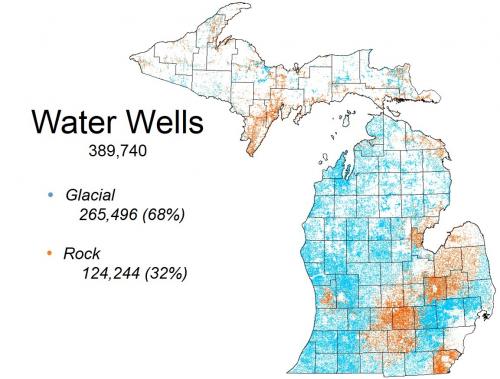

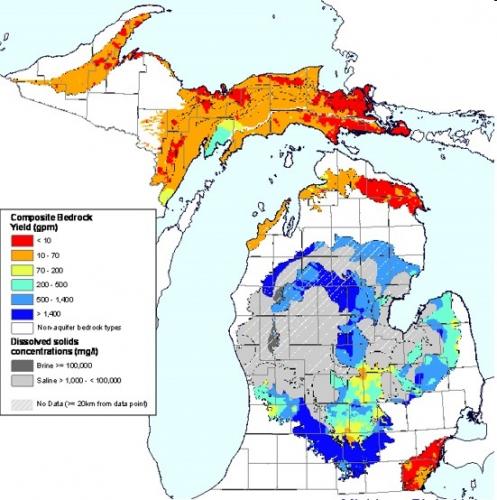

How do these protections work? They address the basic problem: the groundwater we use is vulnerable to contamination from what is put on the surface of the ground. Glacial deposits (soils from the top of bedrock to the surface) are largely permeable. “Permeable” means liquid and contaminants can and does soak through the soil from the surface to groundwater. Most groundwater wells are pulling water from glacial deposits (68 percent). The remaining 32 percent pull water from within bedrock. But a significant amount of the bedrock found in Michigan is also permeable -- Karst bedrock particularly so.

Water wells map, presentation materials by David Lusch, MSU Institute of Water Research.

Bedrock water yield map, presentation materials by David Lusch, MSU Institute of Water Research.

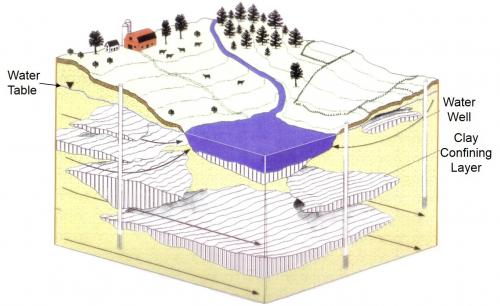

There is a prevalent myth that groundwater is protected if there is a clay soil layer between the surface and water. While clay is a good barrier, it is not failsafe. It too is permeable. The rate of movement of water and contaminants through clay is much slower, and many clay layers are not continuous. Clay layers have holes, cracks and breaks allowing leakage. Therefore, when there is a spill on the surface it is not a question of if surface contamination will reach groundwater, but how long it will take.

Groundwater confining layers map, presentation materials by David Lusch, MSU Institute of Water Research.

With permeability of glacial deposits, surface water (lakes and rivers), wetlands, and groundwater are often inter-connected. Contaminants in one can move to the others. Thus, a protection program really needs to focus on all three: surface, wetland, and groundwater. Local zoning is one of the most effective tools to do this in a way that is preventative. Zoning can often prevent problems from occurring in the first place.

Some believe Michigan, the Great Lakes State, has limitless abundant fresh water. But problems with groundwater have been identified at many locations in the state. Sometimes the issue is much more widespread than isolated locations. In Ottawa County, groundwater has become impaired with wells now pulling up salty water and the overall lowering of groundwater levels throughout the county. See the article "Ottawa County groundwater has quality and quantity concerns."

Not putting in safeguards could come at a high cost since groundwater is always at risk, and cleanup is very expensive, it is advised that communities take precautions with the tools available to them.

Those in Michigan State University Extension that focus on land use provide various training programs on planning and zoning, which are available to be presented in your county. Contact your local land use educator for more information.

Print

Print Email

Email