The modern day study of economics has undergone a considerable realignment toward reality. Where models of yesteryear comfortably made heroic assumptions about the rationality of people involved with a company’s decision-making process, the field of “behavioral economics” has injected a healthy dose of reality into the profession. As behavioral economists, we constantly remind our colleagues that humans are “predictably irrational,” whose decisions can be messy and, at times, inconsistent with an optimal outcome. The remainder of this article outlines five simple principles that can improve farm managerial and agricultural marketing outcomes.

Principle #1: Too many choices can be overwhelming

I can think of no better way to demonstrate this principle than in the modern American beer market. Back in the 1980’s, there were fewer than one hundred breweries. Today, the United States is home to more than 7,000 breweries. Right now, there are more breweries in the state of Michigan than there were in the entire continent of North America in 1985. The proliferation of options has been fantastic for craft beer drinkers, but there are others who might find the new world of beer to be overwhelming. Generally, in economics we assume that providing customers with more options is a good thing, as they are more likely to find the product that best suits their needs — particularly when there is no obvious preferred choice, increasing the number of available options might actually lead a customer to decision paralysis and regret.

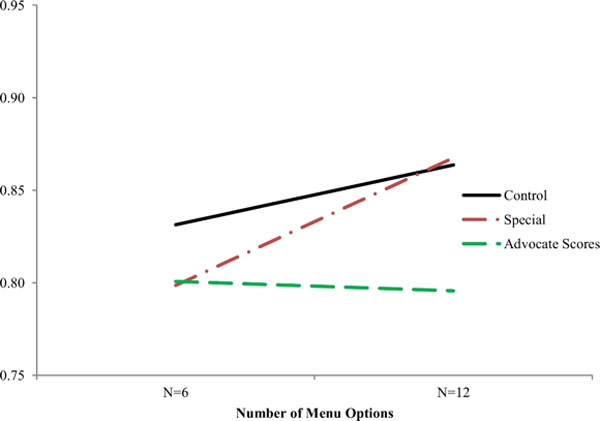

In fact, that is precisely what Jayson Lusk and I uncovered during an experiment on consumer choices in the craft beer market. To test the size of the effect, we doubled the number of craft beers at a wine bar in Oklahoma. By increasing the number of options provided to the customers of the wine bar, we could reduce the number of people who ordered a beer. Even more interesting, however, was that the seller could eliminate the choice overload problem by providing consumers with a third party rating system such as Beer Advocate scores. In a follow-up study, we simulated the same bar experience with a representative sample of U.S. beer drinkers in an online setting. We found that although the average beer drinker prefers more options to less, even experienced craft beer connoisseur appreciated a third party verification on the beer menu. The implications for sellers within agribusiness are clear; your customers will appreciate your efforts in helping them compile objective third party information that might support their decision-making process.

Figure 1: Probability of not selecting a beer in our field experiment. An upward sloping line indicates the presence of choice overload.

Principle #2: Sometimes, it’s not what you say, but how you say it

This simple wisdom has been passed down from mother to child for generations, but it takes on a more important meaning when we think about product labeling. Consider the infamous gluten protein. At first glance, placing a “gluten free” sticker on a bottle of water would seem like a waste of time – all water is gluten free! So why would someone even make that label to begin with? There is a reason: the simple act of making that claim immediately casts doubt on all of the products without the label. In behavioral economics, we would title this a “framing effect” or “anchoring bias.” In a recent study, Brandon McFadden and I tackled this issue in GMO labels. We found that even though the different labels conveyed the same information to consumers, people valued the information differently based on the way the information was framed. For example, younger consumers were more inclined to be influenced by the presence of a QR code on the package than were older consumers.

Figure 2. All of these labels convey similar information, but the QR Code is less effective for older consumers.

Principle #3: Just because you own it, shouldn’t make it more valuable

You can visit farms across the country where at least one barn is full of junk. Sometimes, you can attribute it to what people call a “Depression-era mentality,” where people might have a deep, psychological fear of losing everything. Perhaps at a less problematic level, the effect can be observed in all primates.

Consider the coffee mug on your desk. Your value of that coffee mug should be the same even if you didn’t own it… and yet that is not what we find in the experimental lab. Coined the “endowment effect,” behavioral economists have discovered that people value things more highly if they earned it even if the market value of the product has not changed. The key takeaway for on-farm decisions is threefold. First, giving people ownership of a project is likely to make them value the project’s outcome more so than if they are not given ownership. Second, and perhaps more importantly, knowing about the endowment effect might help agribusiness managers reevaluate their inventory. How much of it really has a market value, and how much of it is just collecting dust? Finally, it is important to remember how to make baseline comparisons. Instead of comparing current prices to the prices from the best years, it is more appropriate to compare to the average year. Using this average value in your budgeting is likely to improve the accuracy of your value forecasts.

Principle #4: Path dependence can prevent good decision-making

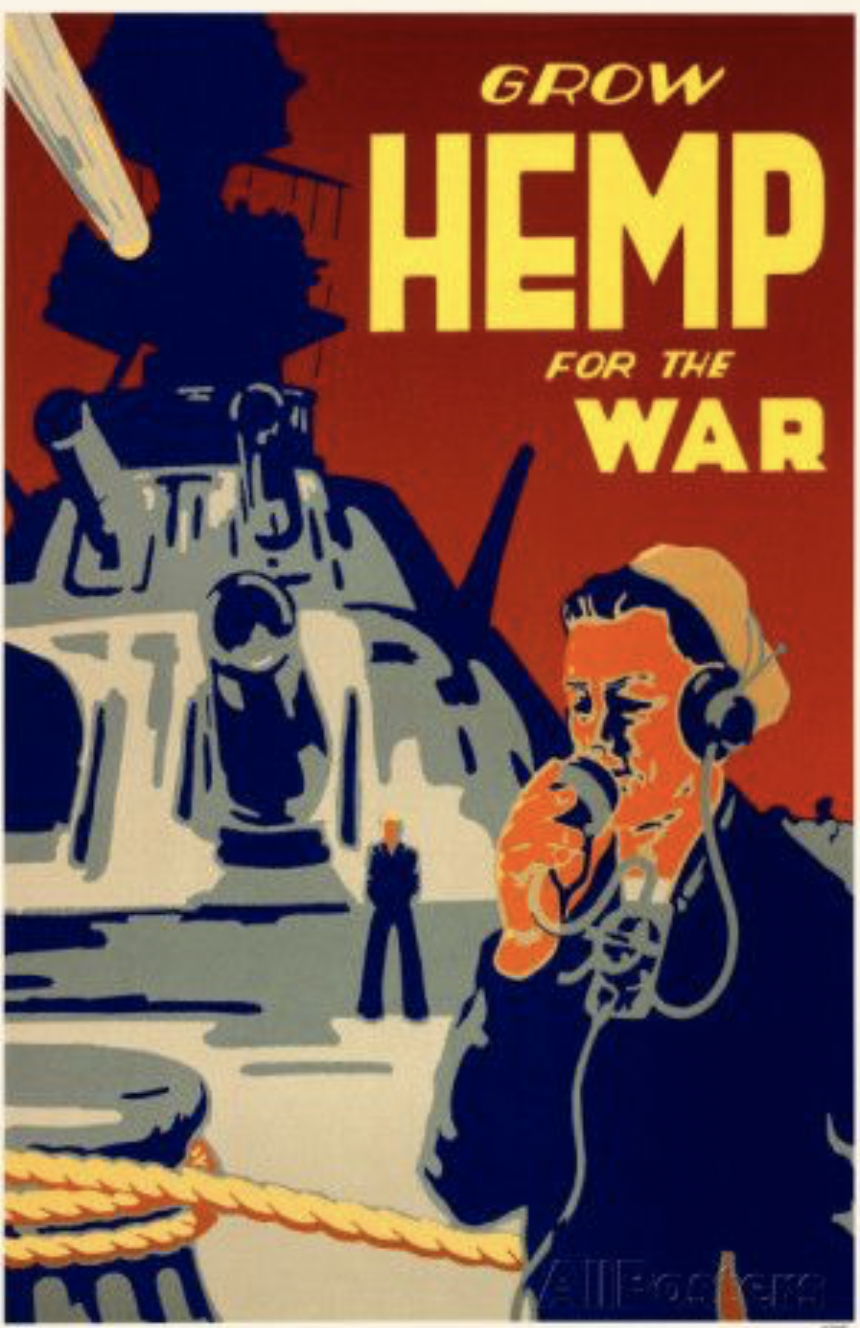

How many times have you heard someone say, “We tried that once and it didn’t work?” This is what we call availability bias: people have an innate tendency toward valuing something if they can remember it easier. For example, it was safer to fly across the United States on 9/11 than it was to drive across the United States. Because it is so much easier to recall a memorable event, people oftentimes overlook important data and opt to revert toward the status quo, creating “path dependent” behavior. Path dependence is not limited just to those of us in the private sector. Sometimes, government policies outlive their usefulness by the simple nature of path dependence. This is perhaps why it takes more than 90,000 federal regulations to get a beer from the hops yard to the pint glass. Another example is the current federal hemp policy. Back during World War II, USDA propaganda advocated “Hemp for Victory,” but industrial hemp farmers ultimately became casualties of the drug war. Even though there is no active psychoactive compound in hemp plants, it has taken decades for the U.S. Farm Bill to consider giving farmers the freedom to commercially grow the crop.

How many times have you heard someone say, “We tried that once and it didn’t work?” This is what we call availability bias: people have an innate tendency toward valuing something if they can remember it easier. For example, it was safer to fly across the United States on 9/11 than it was to drive across the United States. Because it is so much easier to recall a memorable event, people oftentimes overlook important data and opt to revert toward the status quo, creating “path dependent” behavior. Path dependence is not limited just to those of us in the private sector. Sometimes, government policies outlive their usefulness by the simple nature of path dependence. This is perhaps why it takes more than 90,000 federal regulations to get a beer from the hops yard to the pint glass. Another example is the current federal hemp policy. Back during World War II, USDA propaganda advocated “Hemp for Victory,” but industrial hemp farmers ultimately became casualties of the drug war. Even though there is no active psychoactive compound in hemp plants, it has taken decades for the U.S. Farm Bill to consider giving farmers the freedom to commercially grow the crop.

Figure 3: A World War II Poster that advocated for U.S. farmers to convert their production to industrial hemp

These four principles represent just a small sampling of the insights that behavioral economics can provide. At its simplest, the core principle of behavioral economics is that people are not perfect. The best thing that agribusiness managers can do to improve outcomes within their operation is to simplify tasks and to always be aware of the preferences of the person with whom you are transacting.

Print

Print Email

Email