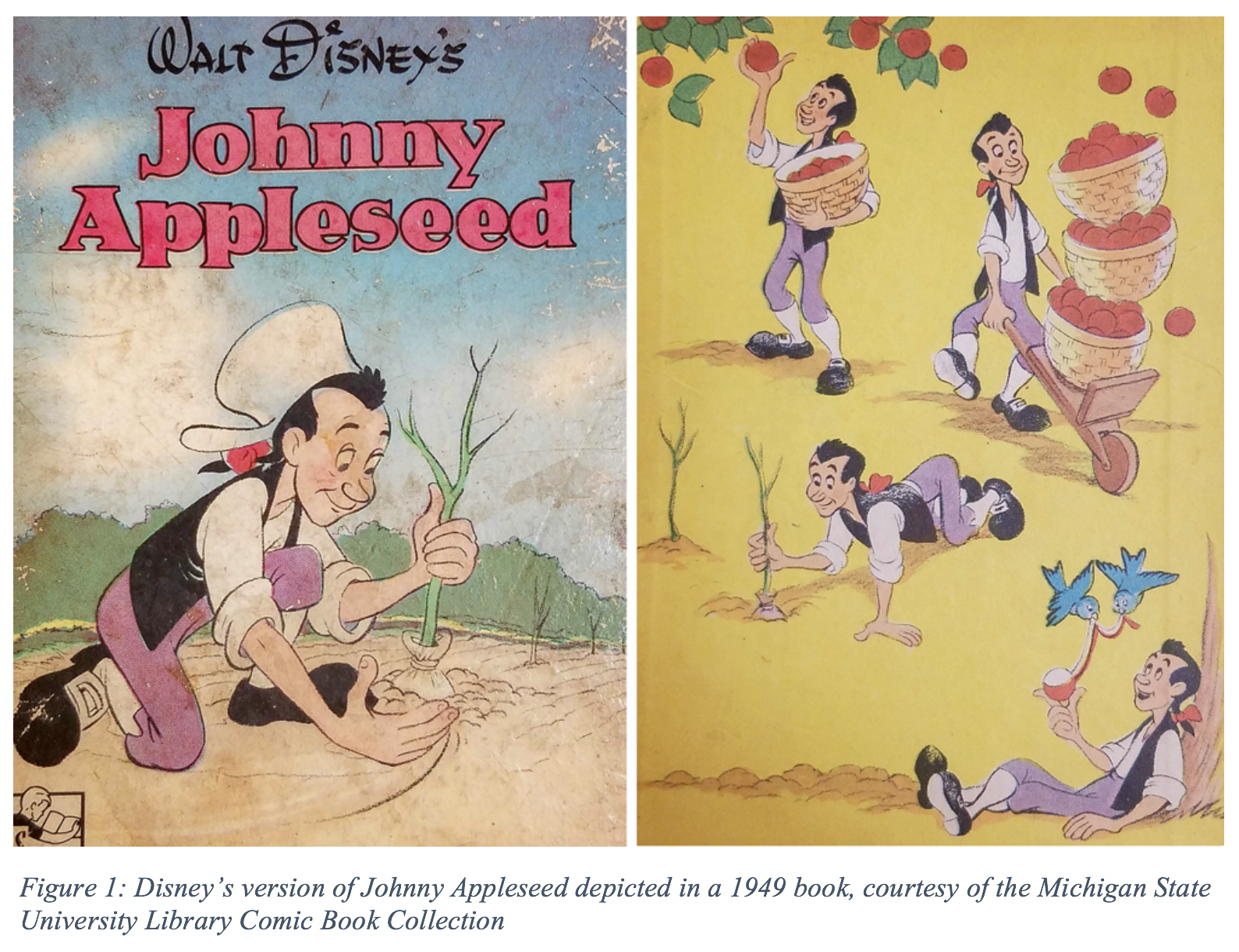

Folk legend Johnny Appleseed wasn’t who you think he was. Johnny Appleseed did plant apples at the beginning of the 19th century, but they weren’t the eating kind. While American folklore conjures up the image of a happy-go-lucky planter of random apple trees, Johnny Appleseed actually strategically planted cider apple orchards throughout the Midwest. Michael Pollan’s Bestseller the Botany of Desire said it best:

“Really what Johnny Appleseed was doing and the reason he was welcome in every cabin in Ohio and Indiana was he was bringing the gift of alcohol to the frontier. He was our American Dionysus.”

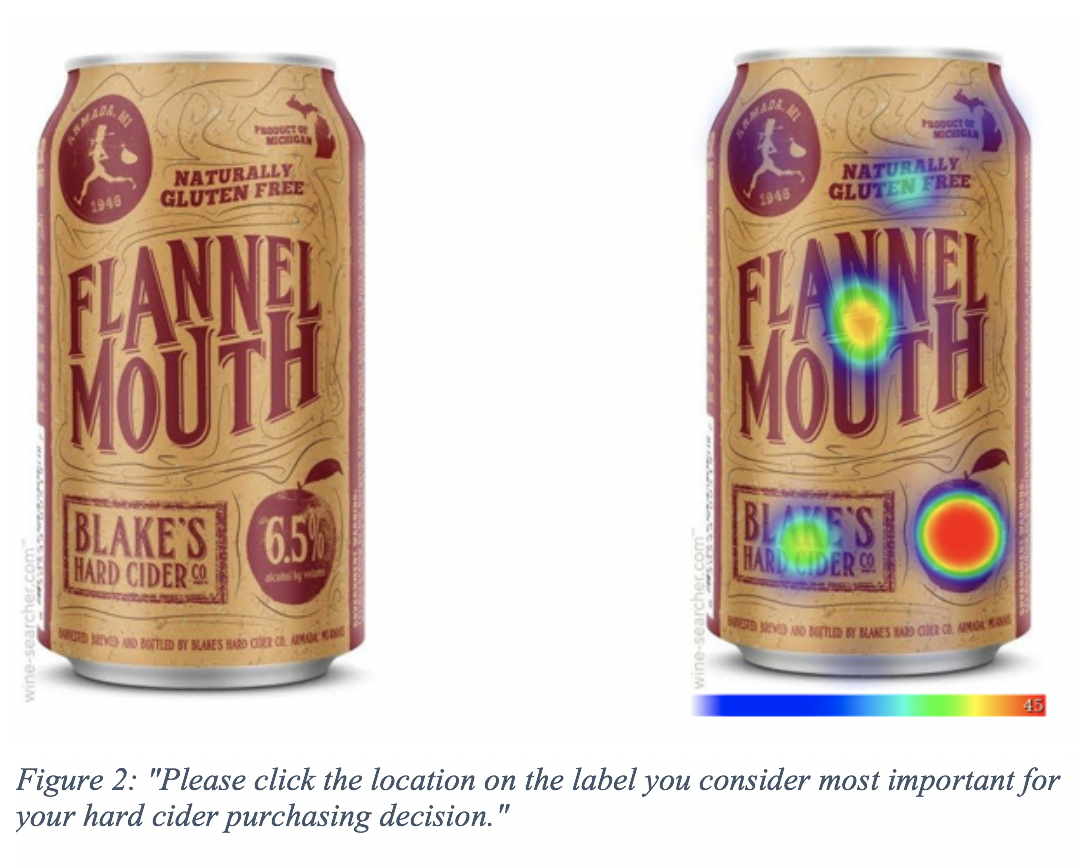

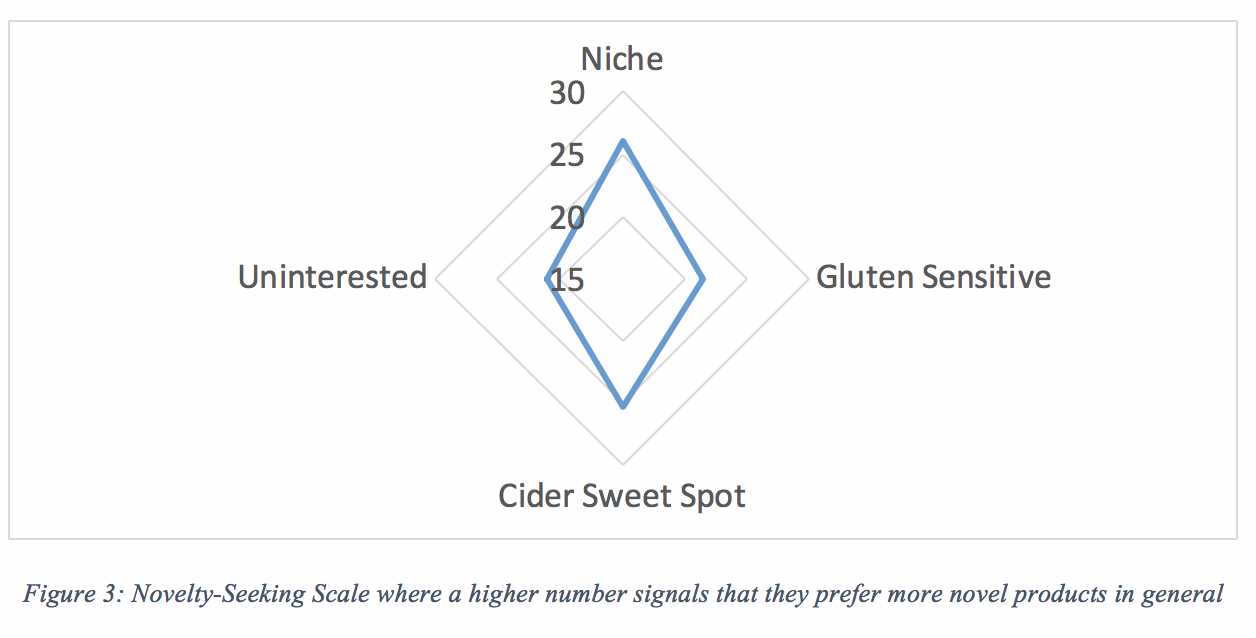

The spirit of this true American hero lives on in Michigan, as we are home to the second-most cider makers in the country. I had the honor of speaking to cider makers at last year’s Great Lakes EXPO. Because I’d only recently dived into the wonderful world of Michigan ciders, I didn’t have many novel things to report. Instead, I explained my first impressions to the producers, which I generated via a pilot survey to a couple hundred likely cider consumers in the United States. First, I presented participants with a popular cider can and asked them to click the location on the label that they consider most important for their purchasing decision. The results were rather surprising. While the name of the cider and the cider maker mattered substantially, survey participants also indicated that they considered the alcohol content, the “gluten free” label (all cider is naturally gluten free), and the cider’s origin. In my preliminary analysis, I grouped my pilot sample into different types of likely hard cider consumers, which is similar to what I did with identifying likely segments of craft beer drinkers.

At least in this exploratory study, was that I could decompose my sample into four different groups: (1) Uninterested, (2) Niche, (3) Gluten Sensitive, and what I called the (4) “Cider Sweet Spot.” Members of the “Cider Sweet Spot” were highly educated, under 35 years old, drank cider frequently, and considered themselves quite knowledgeable of the product (read as “likely hipster”). They were also very interested in novel products.

Just to reiterate, this first-cut was highly preliminary. This past summer, I collaborated with Lindy Robison to explore Michigan cider further. We conducted a stated preferences discrete choice experiment with a representative panel of just over 500 likely cider drinkers in Michigan. We asked each participant a series of eight questions where they chose between a Michigan cider and a New York cider. We systematically varied the cider’s price, alcohol content, and a descriptor of “sweet” or “dry.”

With that data, I estimated a few discrete choice models to identify market segmentation for Michigan hard cider. I could segment these Michigan cider drinkers into three unique categories. In the national pilot study, I could identify 14% of the sample who were in Michigan’s “cider sweet spot.” But Michiganders sure do love their local cider; in this new sample of just likely cider drinkers in Michigan, the sweet spot grew significantly, as 60.4% of the sample preferred the Michigan cider to the New York option. As one would expect, price increases coincided with substantial demand decreases, and most cider drinkers said they preferred a sweet cider to a dry cider.

After the choice questions, we asked each participant to “consider your motives for your decisions to purchase the previous ciders.” Cider is likely to be a “relational good,” which means that social relationships are likely to be embedded in a consumer’s cider-buying decision. To capture this “attachment value,” we presented participants with descriptions of social motives that identified how much attachment value a consumer places on the good they are purchasing. For this preliminary analysis, I included the social capital measure: “I chose this cider as buying from this producer makes me feel like I am supporting workers and owners within my state/nation.” Responses to this statement were higher for the Michigan cider over the New York cider, which signals that local craft ciders have more attachment value than non-local craft ciders — people feel good when they buy “local.”

I then plugged each participant’s response to this question into our discrete choice model and calculated an “attachment value elasticity.” Elasticities are extremely helpful for economists as they help us predict what is likely to happen to demand for a product when one of the product’s attributes changes. The most commonly reported elasticity involves a product’s own price, which can be interpreted as, “if prices were to increase by 1%, we would expect the quantity demanded to decrease by X%.” In this case, our “attachment value elasticities” described what we would expect to happen to a cider’s demand when consumers changed their attachment value with a cider by one percent. Our preliminary analysis suggests that changes in pro-social motivations are substantially more important to driving demand for local ciders than they are for non-local ciders. By extension, our study lends credence to the notion that local food producers might benefit by focusing more marketing efforts on the positive ways they support their patrons via the local community.

MSU has some fantastic resources for anyone interested in Michigan hard cider, including Nikki Rothwell, who is the Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center Coordinator. The industry also provides a myriad of ways to get involved with cider makers. For example, Michigan hosts the Great Lakes International Cider and Perry Competition (GLINTCAP) every spring, which showcases some of the best ciders and perries in the world. The Michigan Cider Association helps promote the industry in the state with events like the Mid-Mitten Cider Fest at Uncle John’s Cider Mill (I’ve been and it’s amazing). Similarly, the United States Cider Association promotes the industry with events such as CiderCon, where the prowess of Michigan cider makers is on display.

As I collaborate with the cider industry to bring the delicious beverage to even more thirsty consumers, I am thrilled to continue the great work of Johnny Appleseed in my small way. I’ve only taken a few small steps on this journey and one of the next cider topics on my agenda is an exciting project with PhD Candidate Jarrad Farris. Using the same dataset, we will use GPS coordinates to determine the driving distance from the survey participant to the cider maker. With that data, we will be able to effectively calculate the effect of consumer proximity on cider choice, thereby contributing to the ongoing debate surrounding “how local is local?” That research should be ready to premier at this year’s Great Lakes EXPO, so be sure to purchase your tickets soon!

To hear more about Dr. Malone’s research on consumer marketing issues, listen to the two most recent episodes of Dr. Bridget Behe’s Connect-2-Consumer podcast.

Print

Print Email

Email