Michigan hop update – June 21, 2013

Downy mildew continues to expand in Michigan hopyards and with rain in the forecast, growers should apply protectant sprays to minimize infections.

So far this season, the Benton Harbor Enviro-weather station has accumulated 793 GDD50 with 0.35 inches of rain over the past week; the Clarksville Enviro-weather station has recorded 695 GDD50 with 0.74 inches of rain this past week; and the Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center accumulated 572 GDD50 with 0.97 inches of rain over the last week. Bine training has wrapped up for the most part and growth really took off this last week with bines as high as 12 feet in northwest Michigan.

Hop development in northwest Michigan on June 20, 2013.

Photo credit: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension

Downy mildew is the major concern for Michigan growers right now, with early initial infections fueling significant outbreaks in some hopyards. Downy mildew is caused by Pseudoperonospora humuli and can cause significant yield and quality losses, depending on variety and when infection becomes established. In extreme cases, cones can become infected and the crown may die.

Typically, downy mildew appears early in the season on the emerging basal spikes. Spikes then appear stunted, brittle and distorted. Asexual spore masses appear fuzzy and black on the underside of infected leaves. As bines continue to expand new tissue becomes infected and bines fail to climb the string. Growers can retrain new shoots, but often incur yield loss as a result.

This season, symptoms have appeared more readily on expanded leaves as small, angular lesions that are yellow and chlorotic in appearance. These small lesions expand over time and eventually sporulate on the underside of leaves when warm and moist conditions occur. According to “A Field Guide for Integrated Pest Management in Hops,” infection is favored by mild to warm temperatures (60 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit) when free moisture is present for at least 1.5 hours, although leaf infection can occur at temperatures as low as 41 F when wetness persists for 24 hours or longer. At this point in the season we are also beginning to see stunting and wilt of terminal portions of the bine.

Small, angular lesions in the early stages of downy mildew infection on the back of a hop leaf. The front of the hop leaf appears to have chlorotic, yellow halos where lesions are located. Photo credit: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension

It takes a multipronged approach to manage for downy mildew. Growers should utilize a protectant fungicide management strategy to mitigate the risks of early and severe infections. Keep in mind that varieties vary widely in their susceptibility to downy mildew and growers should select the more tolerant varieties when possible. Clean planting materials should be selected when establishing new hopyards since this disease is readily spread via nursery stock. It is also recommended that growers pull all basal foliage during spring pruning. Pruning should be performed as late as possible and all green materials should be removed from the hopyard and covered up or burned.

The variety Centennial with advanced downy mildew infections sporulating on the underside of

leaves and causing stunting and collapse of the bine. Photo credit: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension

Cultural practices alone are not enough to manage downy mildew. Protectant fungicide strategies are particularly important during the year of planting to minimize crown infection and limit disease levels in the future. Well-timed fungicide applications just after the first spikes emerge and before pruning has been shown to significantly improve infection levels season long. Subsequent fungicide applications should be made in response to environmental conditions that favor disease (temperatures above 41 F and wetting events). Fungicides containing copper, boscalid, pyraclostrobin, phosphorous acids and a number of biopesticides have varying activity against downy mildew.

For organic growers, OMRI-approved copper formulations are the most effective. Sulfur products applied for powdery mildew protection will not protect again downy mildew. Michigan growers have yet to report significant powdery mildew damage, but given the experiences of hop growers around the United States, growers should keep an eye out for this potentially significant pathogen.

If you already have downy mildew established in your hopyard, cultural practices will be very important in regaining ground. According to David Gent, a hop specialist at Oregon State University, diseased shoots on the string should be removed by hand and healthy shoots retrained in their place. Remove superfluous basal foliage and lower leaves to promote air movement in the canopy and to reduce the duration of wetting periods. If there is a cover crop, it should be mowed close to the ground. If yards have no cover crop, cultivation can help dry the soil and minimize humidity. Keep nitrogen applications moderate.

Growers should also carefully monitor their hops for potato leafhopper populations as this insect has arrived throughout Michigan. Potato leafhoppers move in all directions when disturbed, unlike some leafhoppers that have a distinct pattern of movement. Potato leafhoppers can’t survive Michigan’s winter and survive in the Gulf States until adults migrate north in the spring on storm systems. Although hop plants are susceptible to potato leafhoppers, they can tolerate some level of feeding and growers should be conservative in the application of insecticides. At this time there is no set economic threshold for potato leafhoppers in hops and despite having caught potato leafhoppers two weeks ago, no damage has been reported or observed yet this season.

Potato leafhopper nymphs that have begun appearing around

the state. Photo credit: Mario Mandujano, MSU

Potato leafhopper feeding on hops causes what growers have termed “hopper burn,” which causes necrosis of the leaf margin in a v-shaped pattern and may cause a yellowed or stunted appearance as well. The easiest way to observe potato leafhoppers is by flipping the shoots or leaves over and looking for adults and nymphs on the underside of leaves. Growers may also choose to place two-sided yellow sticky traps in the field to catch potato leafhoppers.

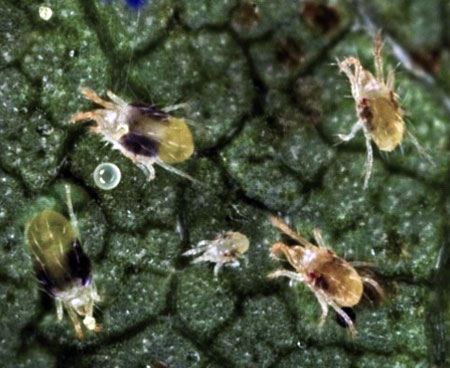

Growers continue to scout for mites and despite some activity in tree fruit, no activity has been reported or observed in hopyards yet this season, though it likely is occurring at a low level. Two-spotted spider mites are a significant pest of hops in Michigan and can cause complete economic crop loss when high numbers occur by decreasing the photosynthetic ability of the leaves and causing direct mechanical damage to the hop cones. Two-spotted spider mites feed on the liquid in plant cells, eventually causing visible symptoms. Leaves take on a white appearance and will eventually defoliate under high pressure conditions. Intense infestations weaken the plant and reduce yield and quality. Infested cones develop a reddish discoloration, do not hold up to the drying process, and commonly have lower alpha levels and shorter storage potential. Additionally, the mites themselves act as a contaminate issue for brewers.

In the spring, only female two-spotted spider mites are present as they have overwintered in a dormant stage from the previous season and are already mated and ready to lay fertilized eggs. She appears particularly orange in color this time of the year and has overwintered on debris and trellis structures in the hopyard. As temperature warm, the females feed and begin laying eggs. Larvae emerge from the eggs in two to five days, depending on temperatures, and develop into adults in one to three weeks – again, depending on temperature. Two-spotted spider mites like it hot with the pace of development increasing until an upper threshold around 10 0F is reached. Conversely, cold and wet weather is not conducive to development, which may explain the low pressure thus far this season.

Two-spotted spider mites are very small, but can be observed on the underside of leaves using a hand lens. The eggs look like tiny, clear spheres and are most commonly found in close proximity to adults and larvae. The larvae themselves are small, translucent versions of the adults that begin the season with a distinctly orange hue that changes over to translucent, yellow or green as they feed. Adults also have two dark spots.

Two-spotted spider mite eggs, larvae and adults (the adult

females are the largest followed by the males).

Photo credit: David Cappaert, Michigan State University, Bugwood.org

When you are observing the underside of leaves, keep an eye out for beneficial, predatory mites that actually feed on the two-spotted spider mite. Predatory mites are often translucent, larger than two-spotted spider mites, and move at a much faster speed across the leaf surface. Predatory mites play an important role in balancing the two-spotted spider mite population and should be protected when possible.

Growers should be scouting for mites now and remember that only when mites reach an economically significant level should cultural and chemical intervention be considered. Scouts should take leaf samples from 3 to 6 feet up the bine; as the season progresses, samples should be taken from higher on the bine as the mites migrate upward. Use a hand lens to evaluate two leaves from 20 plants per yard. Thresholds developed in the Pacific Northwest have established that more than two adult mites per leaf in June indicate the need to implement a pest management strategy. By mid-July, the threshold increases to five to 10 mites per leaf. Remember that if cones are not infested, hop plants can tolerate a good deal of damage from mites.

There are many factors that can affect the prevalence of mites in a given season, including the presence of beneficials, rainfall and temperatures. Consider selecting insecticides that have a minimal effect on beneficial insect populations and do not apply pesticides for mite control unless absolutely necessary as one application often necessitates continual applications in the absence of beneficial predators. Specifically, pyrethroid applications have been shown to increase in mite populations in the hopyard due to their negative impact on beneficial insects.

Growers should read and follow all pesticide labels carefully and proceed with caution when utilizing new materials.

Print

Print Email

Email