MSU researcher fighting tuberculosis, other infectious diseases around the world

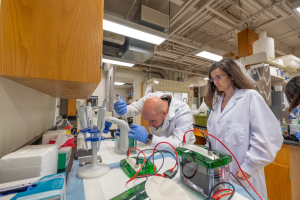

Evangelyn Alocilja is a world-renowned scientist studying infectious disease detection and diagnosis.

Although not on the frontlines in the battle against coronavirus, Evangelyn Alocilja, a professor in the Michigan State University Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering, is closely monitoring the situation. She has even lent her insights on the recent outbreak to international media outlets.

A world-renowned scientist studying infectious disease detection and diagnosis, Alocilja understands better than most the damage these ailments can inflict. They can be particularly devastating to low-income communities that lack access to diagnostic tools and the latest forms of treatment.

Currently, she is teaching two classes on using biosensing techniques for diagnosis. She has had numerous classroom discussions about coronavirus and has asked her students to keep an eye on the situation.

“Much like the diseases I study, such as tuberculosis, coronavirus demands quick diagnosis,” Alocilja said. “We don’t have time to wait for many traditional tests that can take weeks when days and hours matter.”

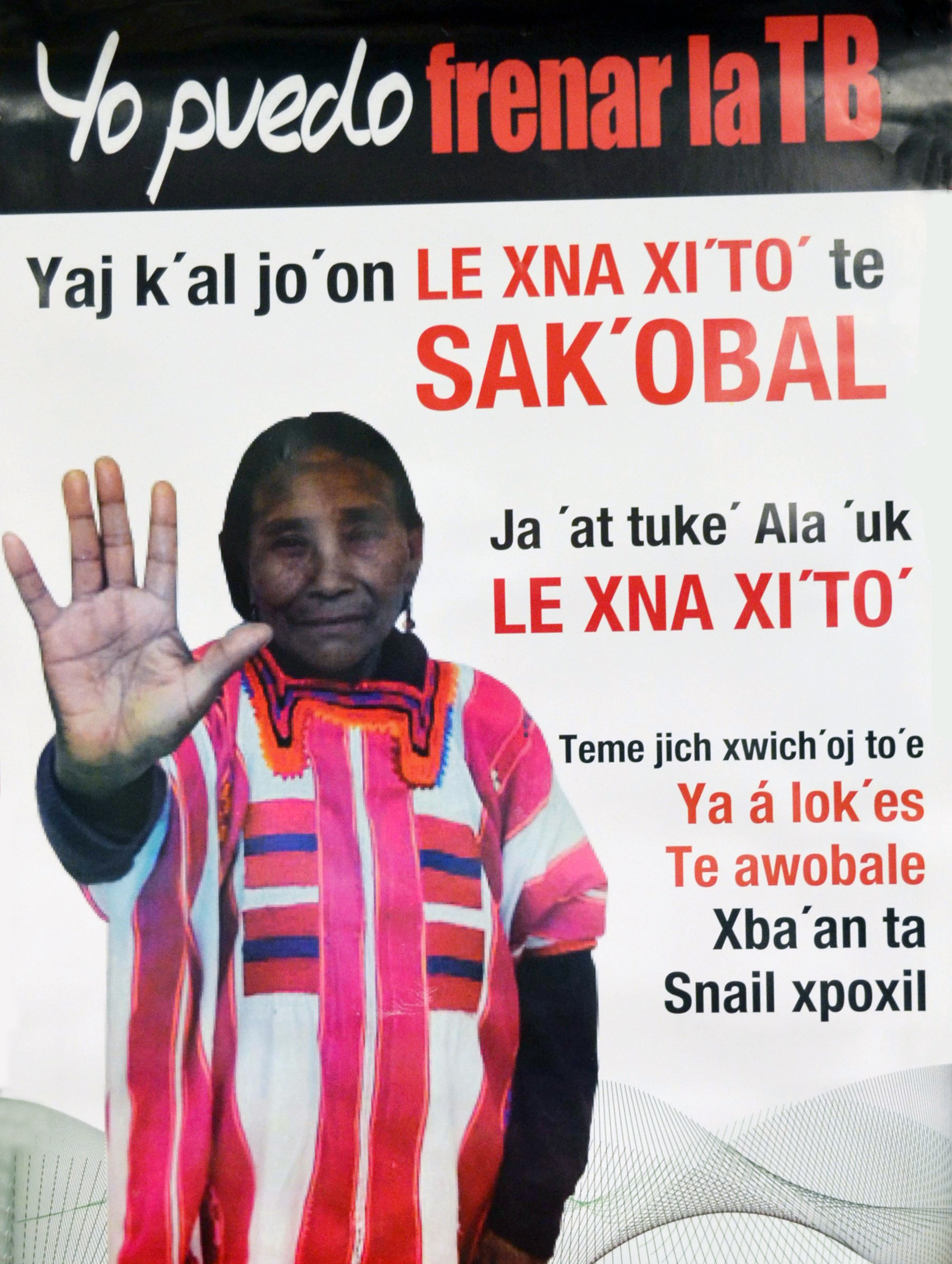

On a wall in Alocilja’s laboratory hangs a poster depicting a Mayan woman with an outstretched arm next to the words “Please stop TB” in multiple Mayan languages. It’s a reminder of why Alocilja comes to the lab motivated each day.

She acquired the poster during a trip to Mexico in 2016, where she witnessed firsthand the hardships caused by tuberculosis on the Mayan community. One woman she met was especially memorable.

The woman’s father had drug-resistant tuberculosis, which requires taking a daily medication for two years. She walked an hour each day alongside her father to a clinic for treatment. Once per month, the duo embarked on a seven-hour bus trip to the nearest city for specialized care.

“It stopped me in my tracks,” Alocilja said. “This is just one person. Millions of people are dealing with this around the world. I started to think about how she had to make so many sacrifices, from work to leaving her children behind so she could join her father on these trips for treatment. I told myself that I had to do something.”

Tuberculosis is the deadliest infectious disease in the world. More than 10 million people are diagnosed each year, and roughly 1.5 million die annually. The World Health Organization estimates that 1.8 billion — about a quarter of the global population — are infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes the disease.

Alocilja is determined to change those statistics. To her, a treatable illness shouldn’t take so many lives. The fight is also personal for Alocilja who lost both her aunt and uncle to the disease while she was a child in the Philippines.

“My philosophy is that people should not get sick and die because they are poor,” Alocilja said. “Some of these areas that have high rates of tuberculosis have limited access to modern tools in both diagnosis and treatment because of the cost.”

With a background in chemistry, biology and engineering, Alocilja has combined each of those skills to become one of the world’s foremost experts on infectious disease detection. She’s been developing tests to diagnose tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus and dengue for more than 20 years.

For tuberculosis, Alocilja has developed a biosensing diagnostic tool that uses nanotechnology to detect the presence of the disease in about 20 minutes. When administered by a trained medical professional, the accuracy is 95 to 99 percent. And with an estimated material cost at 10 cents per test (cost may vary by location), her patented technique is highly affordable.

Alocilja and her team have also created a smartphone app that uses artificial intelligence to read the samples in places where there are no trained professionals to review the results. The accuracy of the app is about 85 percent.

The technology has been validated in Mexico, Nepal and Peru, and results were published in 2018 and 2019. This has led to several other countries inquiring about Alocilja’s invention, including her home country of the Philippines. She has traveled internationally to show medical professionals the advantages of her technique.

To help disseminate information about these new technologies, Alocilja created the Global Alliance for Rapid Diagnostics. The group of researchers and practitioners is motivated by a common goal of saving lives through early diagnosis.

“We want high-performing tools for people who need them the most but can afford them the least,” Alocilja said. “It’s so rewarding to feel like you’re making a difference, and we know if we can be a part of saving lives then we’re really making a difference.”

Print

Print Email

Email