MSU researcher receives Michigan Department of Natural Resources grant to continue lake sturgeon study

Kim Scribner, a professor in the MSU Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, has received a $780,000 grant from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources for research to restore declining lake sturgeon populations in Michigan.

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Kim Scribner, a professor in the Michigan State University Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, has received a $780,000 grant from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) for research to restore declining lake sturgeon populations in Michigan.

The new four-year funding is a continuation of 18 years of MDNR support and partnership totaling roughly $4.2 million. Leading the initiative with Scribner is Edward Baker, an MDNR research biologist.

Since its inception, the project has focused on lake sturgeon populations in the Cheboygan River system and Black Lake. Lake sturgeon are a large freshwater fish that can grow to more than 8 feet long and weigh in excess of 300 pounds. Their prehistoric appearance is highlighted by bony plates on the sides and back of a streamlined body. Lake sturgeon can live up to 100 years, making them the longest living fish in the Great Lakes.

Climate change and overfishing in the 19th and 20th centuries contributed to the decline of the species around the country, particularly in the Great Lakes region. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the species is threated or endangered in 19 of the 20 states it inhabits.

“The main purpose of the study has been to identify the sources of mortality that limit natural reproduction,” Scribner said. “In the Cheboygan River system and Black Lake, we’ve identified 1,200 adults and continue to monitor their breeding efficacy. Overall, the population has been unsuccessful at reproducing effectively, but some individuals are more successful than others. We want to better understand what influences that success or lack thereof.”

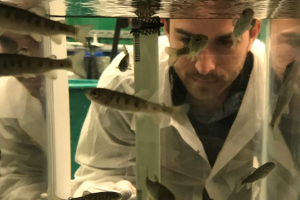

Scribner said eggs and larvae (small, recently hatched fish) from the adult population are harvested by MSU and MDNR researchers and taken to the Black Lake Streamside Rearing Facility for restoration stocking purposes.

Natural reproduction has been inadequate for a variety of reasons, including a low reproductive rate. Male lake sturgeon reach sexual maturity at 15 to 25 years of age, while females take 20 to 25 years. Males spawn roughly every other year and females every three to four years.

Scribner and his team have collected larvae and run genetic testing to determine parentage, letting researchers know which adults are successfully breeding. Each adult is also fitted with a tracking device, allowing Scribner to see when and where spawning is taking place.

Predation during early life stages by other fish species, such as perch and walleye, also limits the number of individuals reaching adulthood. To learn which fish are the primary predators, scientists have used molecular techniques to examine the contents of several fish species’ stomachs.

“It’s important to do this research over a long period of time to collect a large database of information,” Scribner said. “Each year, there are differences in things like temperature and precipitation, and we need to take all of those factors into account.”

In addition to research, the project has a community science component. Children can visit the rearing facility with classmates and see the fish, while hearing about its history. An educational program called Sturgeon in the Classroom allows students in grades 7 through 12 to learn about the lake sturgeon lifecycle and its importance to the ecosystem, and are equipped with a tank in the classroom, eventually releasing the fish into the wild once adequate development is reached.

A citizen science program, in which interested members of the community can get out in nature and help to identify species in the Great Lakes region, is also in its early stages.

“Engaging the community, especially young people, in the conversation is critical to conservation efforts,” Scribner said. “Teaching them about the relationship they have to the environment gets them invested and more likely to care about conservation moving forward.”

Print

Print Email

Email