Postharvest hopyard management

As growers wrap up hop harvest this season they can follow these postharvest tips to prepare for next year.

As the 2013 hop season in Michigan winds down, many growers are reporting a good harvest. As we look ahead to next year, growers begin to explore how they can improve upon this season’s harvest. For the most part, the work of the season is complete but growers can still consider pest management practices that may impact next year, postharvest irrigation, compost application and record keeping.

Tackling downy mildew

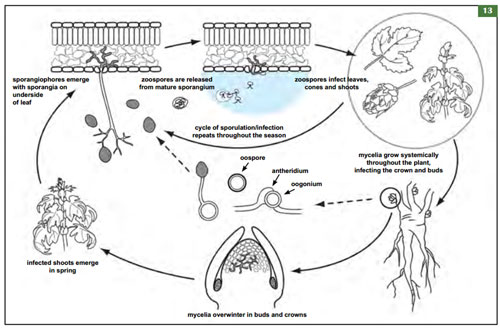

Some growers struggled with downy mildew for the first time this season and are wondering what can be done postharvest to combat this important and damaging disease. To properly answer this question we need to fully understand the disease cycle of Pseudoperonospora humuli, the causal agent of downy mildew of hops (Figure 1) and how growing conditions in Michigan can affect the efficacy of late season treatment. Mycelium, the vegetative part of the downy mildew fungi, overwinters in buds and crowns or debris left on the field. As shoots emerge in the spring they are already infected with this overwintering mycelium. As the hop bine begins to grow, the mycelium produces a microscopic spore-bearing structure (sporangiophore) on the underside of leaves giving the underside a gray, fuzzy appearance. These structures give rise to an asexual type of spore called zoospores.

Figure 1. The disease cycle of Pseudoperonospora humuli, the causal

agent of downy mildew in hop. (Cred. V. Brewster, Compendium of Hop Diseases and Pests)

Click on the image to view larger.

Zoospores move via wind and rain and act as the major cause of disease spread during the season, infecting new leaves, shoots and eventually even cones. The reproductive cycle that produces zoospores may repeat multiple times over the season, depending on temperature and moisture availability. Alternately, mycelium may also yield a resting spore (oospore) that it produces through sexual recombination. Oospores are typically more resistant to environmental changes and are often referred to as resting spores. It is unclear at this time if Michigan’s climate provides environmental conditions conducive to oospore production.

When considering a postharvest treatment, Michigan State University Extension advises it is important to remember that the downy mildew fungi will overwinter in the plant itself and is protected by the plant cuticle. While there is no data to suggest that post-harvest treatments are beneficial in terms of a reduction in disease next season, there is a general correlation between disease presence and severity from season to season that warrants further research. If growers want to try an experimental postharvest application, they should focus on utilizing systemic fungicides that move downward in the plant tissue and might disrupt the mycelium that will be the source of next year’s infection.

Systemic fungicides are typically described as locally systemic, acropetal systemic (moving upward), or basipetal systemic (moving downward). Locally systemic materials are not useful for the treatment of downy mildew at this time because they do not move far from the site of application and don’t reach the sites where the disease overwinters.

True systemic fungicides are taken up by the xylem or phloem tissue of the plant and moved to new tissues. Many of the systemic materials today are only translocated upward via the xylem or water-conducting tissues. Distribution of a systemic fungicide in the phloem or carbohydrate-conducting tissue tissues (basipetal translocation or downward movement) would include translocation into the crown and roots where downy mildew overwinters.

Fungicides labeled for hops that move systemically downward include Aliette and phosphonate fungicides. Given the overwintering location of the fungi, a systemic fungicide with downward movement would be the best option. That being said, with little remaining leaf area and bines shutting down from shorter day lengths there may be limited value to a fungicide application at this time. Based on the lack of supporting data, postharvest treatments for downy mildew are not recommended as a general practice at this time. Growers with high levels of downy in their hopyards should instead focus on developing an aggressive, protectant treatment program for next spring.

Insect pests in the fall

Now let’s consider some of the problematic insect pests still lingering after harvest. Potato leafhopper, damson hop aphid and two-spotted spider mite were all reported at significant levels in hopyards, and growers are considering what treatment strategies are available postharvest.

Potato leafhoppers (Image 1) were a real issue for some growers, but a treatment now would not affect populations next season because the potato leafhopper currently in hopyards will not survive the winter. Potato leafhoppers move north on spring storms each year, reproduce in the hopyards and can cause significant damage. However, their inability to survive the winter wipes out the entire population in Michigan each year.

Image 1. Potato leafhopper nymph and hop leaf covered in nymphs and showing signs of feeding

damage with necrotic leaf margins. Photo credit: Erin Lizotte, MSUE

Damson hop aphid was observed in higher numbers as harvest approached and some growers had problem infestations at harvest (Image 2). Again we must look at the lifecycle of the pest to determine if a postharvest treatment could help keep numbers down next season. Hop aphids overwinter as eggs on Prunus species (genus of trees and shrubs including the plums, cherries, peaches, nectarines, apricots and almonds). In early spring, eggs hatch into stem mothers which give birth to wingless females that feed on the Prunus host. In May, winged females are produced and travel to hop plants where additional generations of wingless females are produced. As cold weather approaches, winged females and males are produced, move back onto a Prunus host, mate and lay eggs for before winter. We expect that this migration off hops and onto plants in the Prunus genus occurs sometime in September.

Growers with particularly high populations could apply a postharvest insecticide to limit the overwintering populations, but only if they are still present in the hopyard. Growers considering an application should scout their fields and confirm the presence of aphids before applications are made. Insecticides containing neem (i.e.Trilogy), imidacloprid (i.e. Admire Pro, Provado 1.6 F and many others), thiamethoxam (Platinum, Platinum 75 SG), flonicamid (Beleaf 50 SG Insecticide) or spirotetramat (labeled as Movento) all have activity against hop aphid.

Image 2. A wingless damson hop aphid on hop.

Photo credit: Erin Lizotte, MSUE

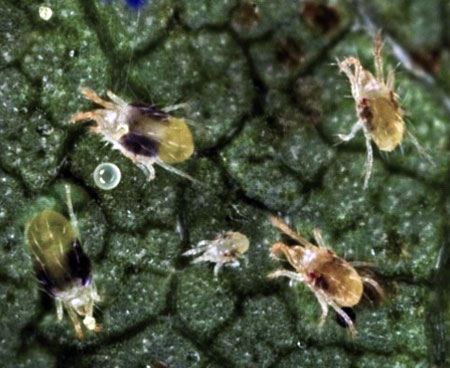

Finally, two-spotted spider mites were an issue for some growers this season. Again, if we examine the lifecycle of the pest we can make better decisions about the potential impact of postharvest management. Hops are a unique situation when it comes to mite management. Many horticultural crops use postharvest treatments in infested sites to reduce overwintering populations, but hop growers remove the plant itself quite early in the season, likely removing a large portion of the mites with it. The two-spotted spider mite that remain, overwinter as mated females on debris and trellis structures in the hopyard.

Mites remaining in the hopyard are susceptible to miticide applications but likely account for a relatively small number in fall when they are beginning to migrate to overwintering sites. Unless the infestations were at an economically significant level, miticide applications should be avoided if possible. Often one mite treatment leads to continued mite treatments as the natural balance of predators and beneficials is upset. For these reasons, postharvest treatments are not recommended unless hopyards are left unharvested and experienced extremely high populations.

Image 3. Two spotted spider mites including females (largest),

males (mid-size) and immature (smallest). Photo credit: David Cappaert, MSU

Growers should also consider the importance of sanitation at this time. Removal of all bines and leaves from the hopyard is recommended. Plant tissues can harbor insects and disease and should be removed, buried or burned. Growers who did not harvest this year (as in first year hops) are advised to remove the plants after a hard frost to prevent increased pest and disease pressure next season.

Growers planning to utilize compost fertilizer can apply it this fall. Recommendations from the west suggest applying a couple of shovels full directly onto and around the crown. Conventional wisdom also suggests watering the bines just before shutting down the irrigation for the year, particularly in areas without good snow cover where desiccation might be an issue this winter. Growers are advised to not fully saturate the soils but keep the final watering moderate, particularly on heavier soils where rot could become an issue.

Take time to evaluate the season

Lastly, it is well worth a growers time to set aside a moment to reflect on the season. Take note of trouble areas in the hopyard, consider planning how to address pest or nutrient issues in the following season. It is also recommended that growers review their spray records and ensure they are complete.

For more information on record keeping visit the resources page of the MSU Pesticide Safety program.

For more information about growing hops in Michigan and the Great Lakes region, visit hops.msu.edu

Print

Print Email

Email