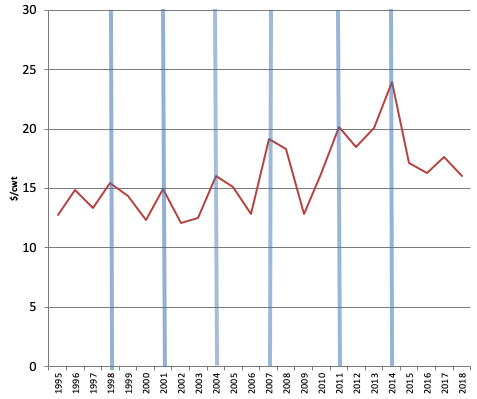

In recent years, it has become accepted conventional wisdom that US farm milk prices follow a three-year cycle. Since the late 1990’s the Dairy Price Support Program generally no longer interfered with farm milk prices, allowing market forces to determine the milk price. Figure 1 displays average US all milk price from 1995 through the first 10 months of 2018. As the figure indicates, beginning in 1998 a price peak occurred about every 3 years through 2014—although one cycle was a four year interval.

Were these true cycles? One could certainly fit a model that would support price cycles. The classic agricultural cycle is the cattle cycle which is thought to be about nine years. For beef cattle, the inventory of breeding cattle tends to move counter cyclical to farm prices. To increase the quantity of beef produced, farmers need to retain more heifers for the breeding herd who later produce calves. The biological process takes several years resulting in a long cycle.

Biologically, a three year cycle is intuitive for milk supply response. In order to increase the milk cow herd, heifer calves must be retained beyond simply replacing cull cows and these heifers must be raised to calving to produce milk. One can easily see how a three year lag could make sense between the decision to increase or decrease milk supply and actual, significant supply changes. This explanation implies that it is a cycle of supply over-reaction that drives farm milk prices.

Because it seemed to fit the situation so well, an expectation of a regular milk price peak became standard. However, following the exceptionally high milk prices of 2014, low farm milk prices—and more importantly low returns—have occurred in 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018. Where is the next farm milk price peak that financially distressed farmers need? The answer, and this is of little use, is it’s not clear but it will happen at some point due to demand and/or supply shocks.

A couple of significant changes occurred in the period examined with potential price cycles. One is that the US became much more reliant on export markets—particularly to sell milk proteins. Prior to 2004, the US generally exported no more than five percent of its milk production. Since that time, US dairy exports have grown to be 15 percent or more of annual milk production. In particular, the US exports of whey proteins and non-fat dry milk have resulted in a strong correlation between US and world prices of these products. The second change was the increasing cost of feed grains related to the adjustment to ethanol mandates which occurred beginning in 2007.

Because both demand for and supply of milk are so inelastic, small, unexpected changes in quantities can result in large changes in price. With respect to farm milk price peaks, consider the situations related to the previous peak years for patterns.

- 1998 is the first peak in the period examined. This peak was related to very strong demand where commercial disappearance of dairy products. In addition, weather events in California (El Nino related) limited milk production.

- 2001 followed a low milk price year in 2000. Milk supply response was again limited by weather events—particularly in the Southwest US.

- 2004 followed two years of low milk prices. Cooperatives Working Together also removed cattle that year curtailing supply response to profitable margins.

- 2008’s milk price peak was related to a large increase in cost of production related to input costs.

- 2011’s milk price peak was related to strong demand including then record-high exports coupled with high hay and cull cow prices.

- 2014’s strong milk price as related to strong international markets including very large Chinese purchases as well as drought in California and New Zealand.

The summary suggests that these farm milk price peaks were due to both demand and supply shocks. The bottom line is that the evidence for the three year cycle is mixed.

Since 2014, the US milk price has languished. In March 2015, the EU milk production quota ended and many European countries witnessed large increases in milk production. Further trade international issues such as the Russian sanctions affected demand for dairy products. Finally, 2018 has witnessed a conflict with China and renegotiating NAFTA resulting in uneven demand for US dairy exports.

What will it take to get a higher US milk price? (Note that this does not address Michigan specific issues related to cost of transporting and marketing excess milk production that will require an alignment of processing capacity and farm milk supply.) To get a higher US farm milk price will require a supply and/or a demand shock. Supply shocks may be related to issues such as weather that affects production conditions or feed costs. El Nino weather patterns may result in cattle or feed effects that can produce higher milk prices. Similarly, higher than expected demand could come from China or other countries with expanding economies.

Given that futures markets currently expect Class III and IV milk prices that are in line with the most recent years ($15-16.50/cwt) and not particularly profitable, what can dairy farmers do with respect to milk marketing? One action is getting a handle on current and expected cost of production for 2019. A careful accounting of not just cash costs but unpaid and overhead factors can reveal what kind of milk price is necessary to cash flow and achieve profitability. Benchmarking these values can help identify whether there are areas that might be candidates for action. With these cost values in mind, farm managers can also think about using tools such as the Dairy Revenue Protection program to protect against lower milk prices particularly in the second half of 2019. Also, perhaps we will soon have a new farm bill. The next farm bill will almost certainly contain a new version of the Margin Protection Program that includes the option to protect higher income over feed cost levels for the first 4 or 5 million pounds of milk production history.

US All Milk Price, 1995-October 2018

US All Milk Price, 1995-October 2018

Print

Print Email

Email