Proving a practical difficulty for a dimensional variance request

While inherently rigid, there are mechanisms in zoning to allow for flexibility.

A zoning ordinance is inherently rigid. Within this rigid structure of zoning are the definitions of where suitable uses can take place, the bulk or scale of those uses allowed, how those uses are accessed, etc. There must also be mechanisms for flexibility based on statutory (Michigan Zoning Enabling Act) and Constitutional (5th Amendment) grounds. Zoning must allow for differences in types of allowed uses, physical characteristics of the land, unique needs of neighborhoods and to prevent infringement on constitutionally protected property interests.

One mechanism for flexibility in zoning is the variance. A variance is the authority to depart from the literal application of the zoning ordinance because of an Unnecessary Hardship (in the case of a use variance) or a Practical Difficulty (in the case of a non-use or dimensional variance) resulting from the physical characteristics of the land. This article will focus on dimensional variances and the principles that amount to a showing of a practical difficulty.

Dimensional Variances

The Michigan Court of Appeals has applied the following principles in dimensional variance court cases, which collectively amount to the showing of a practical difficulty (National Boatland, Inc. v. Farmington Hills ZBA, 146 Mich App 380 (1985)):

- Strict compliance with the standard would unreasonably prevent the landowner from using the property for a permitted use or would render conformity necessarily burdensome.

- The particular request, or a lesser relaxation of ordinance standard, would provide substantial justice to the landowner and neighbors;

- The plight is due to unique circumstances of property and is not shared by neighboring properties in the same zone.

- The problem is not self-created.

Again, the standards come from case law. The Michigan Zoning Enabling Act does not define what a practical difficulty is, though the statute does state “the ordinance shall establish procedures for the review and standards for approval of all types of variances” (Sec. 604(7)). Therefore, the zoning ordinance shall include these standards and may include additional standards that apply to dimensional variance requests.

Seeking Alternatives

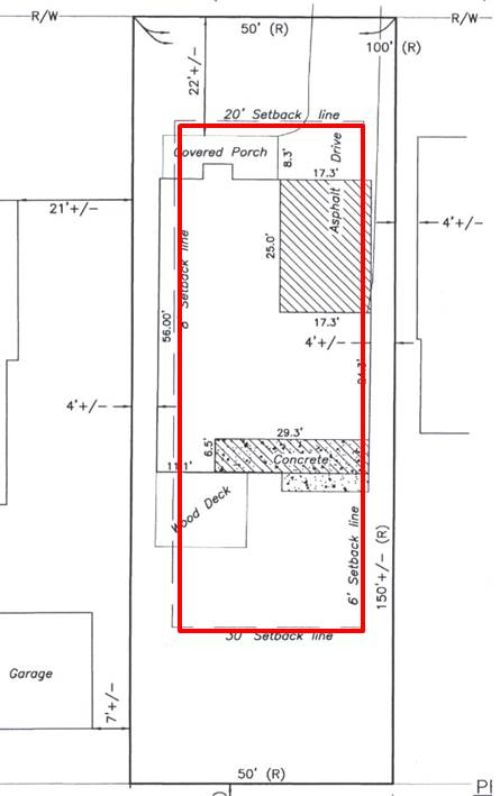

For the first standard (above), the zoning board of appeals (ZBA) should figure out if there is a way to accomplish the same purpose without a variance even if it will be more inconvenient or more expensive for the applicant. If so, a variance should not be granted. For example, if the design for an addition proposed by the applicant can be changed such that a variance is no longer needed, the variance request should be denied (see Figure 1). A variance is granted for circumstances unique to the property (e.g. odd shape), not those unique to the property owner (e.g. large family).

Is there another option?

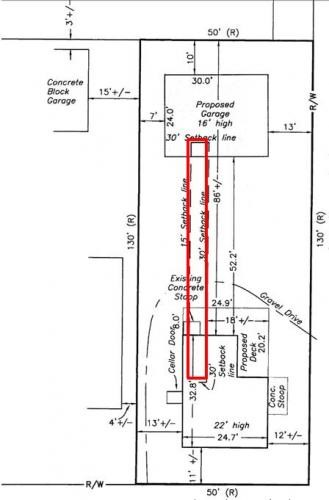

On the second standard, there are valid health and safety reasons for zoning setbacks, but when these regulations treat an applicant unfairly in relation to unique aspects of the land they should be relaxed. However, if a lesser variance than requested would provide substantial justice to the property owner, the lesser variance should be considered. For example, if the request is to encroach into the setback by 4 feet, but a 2-foot encroachment would allow the owner to use their property for the permitted use then the appeals board must not approve a greater variance than minimally necessary (see Figure 2).

Amending an ordinance

Third, if the circumstances for which a variance is warranted are shared among numerous properties in the same zone, then the variance request should be denied. It may be better to consider amending the zoning ordinance. For instance, a historic portion of a community developed around the turn of the 20th Century might have 50-foot lots throughout a neighborhood of single-family homes. If this neighborhood is subject to the same zoning standards as neighborhoods developed later with 70-foot-wide lots, projects not requiring a dimensional variance in the newer neighborhood will most likely require a variance in the historic neighborhood. The proper solution is to create a new zoning district for the historic neighborhood that is more reflective of the existing character (see Study neighborhood typology to discover a library of information on form).

Is the issue "self-created"?

The fourth standard is widely misunderstood among ZBA members. The proper interpretation is to ask whether the applicant took some affirmative action that created the need for the variance, such as making an unusual land division (shape), filling the entire building envelope so that a porch must necessarily extend into the setback area, digging a pond, etc. A practical difficulty cannot be self-created (Norman Corp v. City of East Tawas, 263 Mich App 194 (2004)). Being “self-created” includes actions of the current property owner and actions of all previous owners.

In other words, a self-created practical difficulty by a predecessor in title can bar a subsequent owner from a legitimate variance request (Johnson v. Robinson Twp, 420 Mich 115 (1984)). At the same time, the Court of Appeals recognizes that merely purchasing property with the knowledge of ordinance limitations does not preclude someone from apply for (and receiving) a variance (City of Detroit v. City of Detroit BZA, 326 Mich App 248 (2018)). The key is whether a property owner — present or past, took affirmative action to alter the property counter to the controlling ordinance at the time. The purchase of a unique lot, even with knowledge of the current ordinance, should not be held against a new owner. This standard is inappropriately applied if a ZBA member sees the presence of the applicant before the ZBA as a self-created situation. This mindset would lead to the conclusion that all variance requests are self-created. It is not an applicant’s desire for a variance that is a self-created problem; it is an applicant’s previous action to fill the buildable envelope with structures, or divide the parcel into an unusual shape that is the self-created problem.

Lastly, it is important to note that all the standards that amount to the showing of a practical difficulty must be satisfied in order for a variance to be granted. The list of standards from the Court of Appeals, and any additional standards in the zoning ordinance, must all be satisfied in order for the applicant to have a practical difficulty. The collection of facts that satisfy all of the applicable standards must then be captured in the record to document the reasons for the decision (see How to take Minutes for Administrative Decisions).

The role of the ZBA member is an unenviable one. Board members are asked to apply the standards described in this article (and possibly more) to the requests of perfect strangers, acquaintances, and friends alike (outside of a bona fide conflict of interest) and do so consistently and without bias. Doing so is easier when all members of the ZBA understand the standards in the ordinance and have reference material in front of them at each meeting that spells out what constitutes a practical difficulty (or unnecessary hardship). Michigan State University Extension offers training for ZBA members to help them make more legally defensible decisions. Contact a land use educator to learn more.

Print

Print Email

Email