Smarter manure management: New tools to save nitrogen and protect the environment

Two recent studies from UW–Madison are testing ways to keep more nitrogen in the soil where crops can use it, while cutting down on pollution.

Manure is a valuable resource for farmers. It provides crop nutrients, adds organic matter to the soil and contributes to the soil foodweb. If not managed carefully, too much nitrogen can harm the environment. Nitrogen can volatilize into ammonia and escape into the air or be converted into nitrate and leach into surface and groundwater. Ammonia and nitrate are forms of nitrogen unavailable for plant uptake.

Manure is a valuable resource for farmers. It provides crop nutrients, adds organic matter to the soil and contributes to the soil foodweb. If not managed carefully, too much nitrogen can harm the environment. Nitrogen can volatilize into ammonia and escape into the air or be converted into nitrate and leach into surface and groundwater. Ammonia and nitrate are forms of nitrogen unavailable for plant uptake.

Two recent studies from UW-Madison are testing ways to keep more nitrogen in the soil, where crops can use it, while cutting down on pollution.

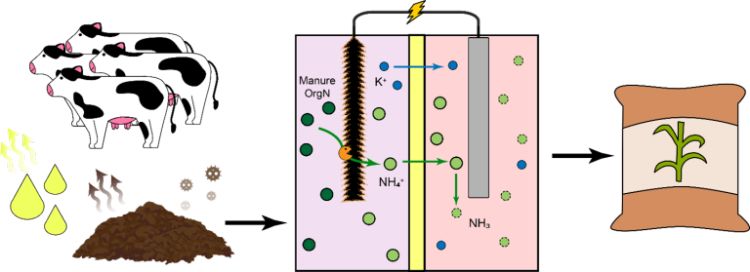

Study 1: Using electricity to recover nitrogen from manure

One team of researchers tested a new technology called a bioelectrochemical system (BES). This system uses crores and electricity to break down manure and collect nitrogen into a form that plants can use.

The system has two chambers separated by a membrane. The manure goes into one chamber, where microbes break it down. Electricity helps move nitrogen across the membrane into the second chamber, where it turns into ammonia fertilizer.

They tested the system with both lab-created (synthetic) manure and real dairy manure. Here's what they found:

- The system removed over 90% of organic matter from synthetic manure.

- It removed up to 60% of nitrogen when running on electricity.

- Real dairy manure also showed about 60% nitrogen removal, but it worked a little less efficiently due to extra materials in the manure.

The researchers also built a model for a 730-cow dairy farm to compare this system to other ways of handling manure:

- No treatment (direct application)

- Solids-liquid separation

- BES treatment

The BES system reduced ammonia loss and the risk of water pollution better than the other methods. “When treating real dairy manure, the system achieved average removals of 60% of total nitrogen and 58% of organic matter,” researcher McKenzie Burns said. It did use more energy, approximately 1,700 kWh of electricity per week to meet pumping and aeration demands, some of that power could come from the electricity generated by the system itself.

Study 2: How manure application methods affect nitrogen loss

Another team studied how different manure spreading methods affect how much nitrogen is lost to the air or water.

They applied liquid dairy manure on a silt loam field using six treatments:

- Surface spread

- Surface spread with a urease inhibitor (a product that slows nitrogen loss)

- Incorporated into the soil

- Injected below the surface

- Injected with a urease inhibitor

- No manure (control)

They then planted corn silage and measured:

- Ammonia in the air

- Nitrate in the water

- Corn yield

- Nitrogen use by plants

Here’s what they found:

- Corn yields were similar across all treatments where manure was applied.

- Nitrogen uptake by corn was also similar.

- Ammonia loss was lowest with injection, especially when using a urease inhibitor.

- Nitrate leaching was highest with incorporation and injection, which may be due to faster nitrogen availability.

This study shows that no method is perfect. Reducing ammonia loss can sometimes mean more nitrate leaching. Still, using injection with inhibitors may offer a good balance.

What’s next?

The research teams of Mohan Qin, Rebecca Larson and Mathew Ruark plan to:

- Study manure breakdown speeds to build better models.

- Test the BES system with less water and more energy reuse.

- Try adding biochar to the soil to see if it can reduce both ammonia and nitrate losses.

These efforts will help farmers choose smarter manure practices that work for their land, crops and community.

What this means for farmers

These two studies show there is no one-size-fits-all answer for manure management. But they offer promising tools and strategies:

- New technology like BES could recover nitrogen before it even reaches the field. This helps turn manure into a more precise, easy-to-use fertilizer.

- Application methods matter. Injecting manure or using inhibitors can help reduce nitrogen losses.

- Watch for trade-offs. What helps air quality (less ammonia) may hurt water quality (more nitrate), and vice versa.

By choosing the right tools and methods, farmers can save money on fertilizer, grow strong crops and protect the environment.

This article is a synopsis of presentations given by McKenzie Burns and Juma Bukomba at the Waste to Worth Conference April 7-10, 2025.

Print

Print Email

Email