The evolution of Michigan viticulture and pruning systems

Expanding the relevance: Guyot pruning in other cool-climate regions.

Over the past four decades, Michigan’s wine industry has experienced a significant evolution, from a region focused largely on cold-hardy hybrids to a state increasingly recognized for high-quality Vitis vinifera wine production. Forty years ago, vineyard acreage in Michigan was split roughly 50/50 between vinifera and French-American hybrids. This balance reflected a practical response to the state’s challenging climate, with growers prioritizing winter hardiness and disease resistance over varietal prestige. However, steady advances in viticultural practices, particularly in site selection, canopy management and disease control, have dramatically shifted the landscape. Coupled with the effects of a warming climate, these developments have enabled vinifera cultivars to not only survive but thrive in Michigan’s cool-climate regions.

Today, approximately 70% of Michigan’s vineyard acreage is planted with Vitis vinifera. The industry has narrowed its focus to a core group of cultivars: Riesling, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc and Cabernet Franc, that have demonstrated consistent success under local conditions, and they represent more than 65% of the total wine grape acreage. These varieties are known for their ability to produce wines with crisp acidity, expressive aromatics and strong varietal identity, qualities that have helped elevate Michigan’s profile on the national stage.

Since the early 2000s, the state’s wine producers have increasingly targeted premium markets, fine dining establishments, national wine competitions and boutique retailers, with wines that reflect both regional character and technical precision. This shift represents not just a change in grape selection, but a broader maturation of Michigan’s viticultural identity.

Evolving vineyard practices: Pruning systems for premium wine production

As Michigan’s wine industry has evolved, so too have its vineyard management practices, particularly in the areas of pruning and training systems. In the past, growers often experimented with divided canopy systems such as Smart-Dyson, Geneva Double Curtain and Scott-Henry. These methods were designed to optimize sunlight penetration and manage vigorous growth. However, under Michigan’s variable climate, these systems often proved too complex and led to inconsistent fruit quality. As the industry has matured, growers have shifted toward simpler, more efficient systems that better support vine balance, disease management and fruit uniformity. Among these, the Guyot pruning system, paired with a vertical shoot positioning (VSP) trellis, has become the method of choice for many of Michigan’s leading vinifera cultivars.

The Guyot system is particularly well-suited to cool-climate viticulture. It allows for consistent shoot positioning, better control of crop load and compatibility with mechanization. Instead of maintaining permanent cordons with short spurs, growers using the Guyot system renew fruiting wood annually by selecting one or two healthy canes. This approach ensures retention of the most fruitful buds, typically located in the mid-section of the cane, and helps maintain consistent yield and fruit quality, especially in cultivars that exhibit poor basal bud fertility. However, cane pruning requires precision and annual renewal, as well as proactive protection against winter injury and trunk disease. The following section outlines best practices for implementing the Guyot system effectively in Michigan vineyards.

While this article focuses on applying the Guyot pruning system in Michigan, the principles outlined are broadly relevant to cool-climate viticulture worldwide. Regions such as New York’s Finger Lakes, Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula, and parts of Germany, Austria, Northern Italy and France share similar climatic challenges, short growing seasons, winter injury risks and variable bud fertility. In all these areas, successful grape production depends on careful vine balance, precise pruning and the retention of fruitful wood.

The Guyot system offers a flexible and proven framework in such environments, particularly for Vitis vinifera cultivars with poor basal bud fertility. By renewing fruiting wood annually and focusing on mid-cane bud retention, growers can optimize yield consistency and fruit quality even in challenging vintages. Furthermore, the system’s compatibility with mechanization and sustainable canopy management makes it increasingly attractive in modern vineyard design. As climate conditions shift, growers across diverse regions may find renewed value in the adaptability of the Guyot system, not just as a legacy technique, but as a forward-looking tool for resilient, quality-driven viticulture.

Guyot pruning: Nine guidelines for effective winter practice

The Guyot system, developed in the 19th century by French agronomist Jules Guyot, remains one of the most widely used cane-pruning systems in premium viticulture around the world. Below are nine key principles for applying this system effectively in Michigan’s cool-climate vineyards.

1. Spur and cane positioning

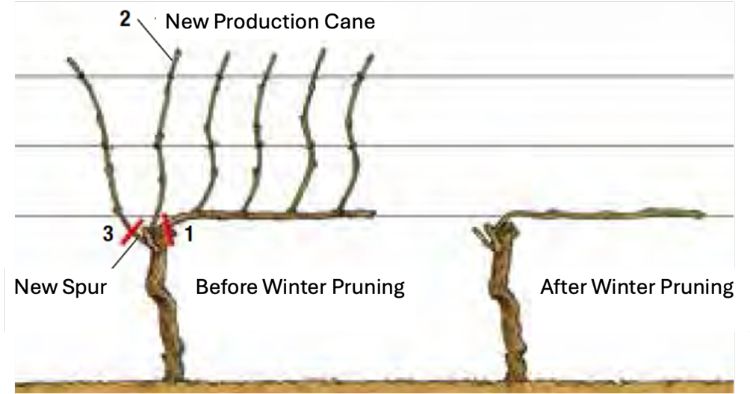

The renewal spur should be pruned to two buds. The distal bud will produce the next year’s fruiting cane, while the basal bud becomes the renewal spur. Always place the renewal spur below the fruiting cane to avoid competition between reproductive and vegetative growth (Figure 1). If only one suitable shoot is available, it may serve as the fruiting cane, with a new spur selected from the crown during the growing season.

2. Maintain a low vine head

To prevent the crown from creeping upward, which can hinder cane bending and uniform shoot emergence, select renewal spurs from shoots close to the trunk or older wood. This preserves even sap flow and reduces the risk of deadwood and vascular congestion. Maintaining a low vine structure also facilitates long-term vine health and productivity.

3. Manage bud count according to vigor

Cane length and bud number should reflect vine vigor and rootstock-scion interaction, not just spacing. Low-vigor vines should carry fewer buds to avoid overcropping, while high-vigor vines can support longer canes. In Michigan, typical practice is to retain eight to 10 buds per cane, based on moderate vine vigor at a spacing of approximately 3 x 7 feet (in-row x between-row). Extending the fruiting cane beyond eight to 10 buds—a practice sometimes seen when growers attempt to "bridge the gap" between missing vines—can significantly increase the risk of overcropping, intensifying both vegetative and reproductive growth. This results in dramatically reduced fruit quality, uneven ripening and excessive shoot development.

While this approach may seem like a short-term fix, it compromises vine balance and undermines vineyard productivity in the long run. This practice should be avoided at all costs. Instead, replanting missing vines should be a top priority to maintain consistent spacing, ensure vine balance, and preserve overall fruit quality across the block.

4. Understand bud fertility

Certain cultivars, such as Riesling and Chardonnay, may have lower fertility in basal buds under Michigan’s cooler spring conditions. Early bud break in low-thermal environments can lead to poor floral differentiation and small clusters. For these cultivars, avoid including the first one to two buds in your productive count and instead position them low on the trunk to avoid crowding at the fruiting wire.

5. Select the best cane

After removing the previous year’s cane, assess remaining shoots for potential use. Prioritize those with good vigor, proper orientation and no physical damage. Tie the chosen cane to the wire before removing alternatives to avoid losing your best option if breakage occurs. Keeping a backup cane during this step is recommended. If necessary, canes from latent buds on older wood can be used, especially after winter damage. While their position may not be ideal, they can restore productivity until more optimally placed shoots emerge the following season.

6. Avoid inward-facing shoots

Exclude canes and buds oriented toward the row interior, as they are more vulnerable to damage from equipment during operations such as hedging, spraying or harvesting.

7. Protect crown buds

Avoid injuring crown buds (the basal buds near the cane’s base), as they are critical for developing next year’s renewal spurs. Damaging these can limit future pruning options.

8. Minimize cuts on old wood

Because grapevines have limited capacity to compartmentalize wounds, cutting into old wood increases susceptibility to trunk diseases. Make pruning cuts on two-year-old wood whenever possible and avoid wounding permanent wood.

9. Respect the desiccation cone

When cutting into older wood is unavoidable, make cuts several centimeters away from the cane’s point of origin, roughly twice the cane’s diameter. This leaves space for the natural desiccation cone to form, minimizing dieback into the vascular system of the trunk.

As Michigan continues to refine its identity as a premium cool-climate wine region, precision in pruning and vine management will be essential to sustaining high-quality production. The Guyot system, when implemented with care and adapted to cultivar-specific needs, provides a reliable and efficient framework for achieving consistent yields, optimal fruit quality and long-term vine health.

Print

Print Email

Email