The less traveled pathways for species introduction to the Great Lakes

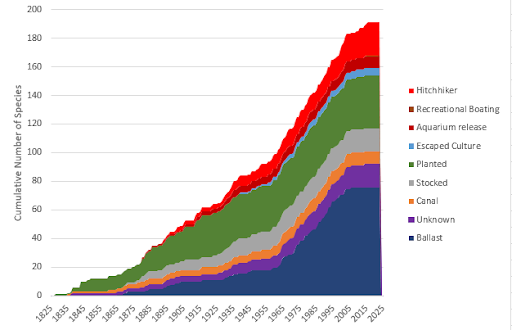

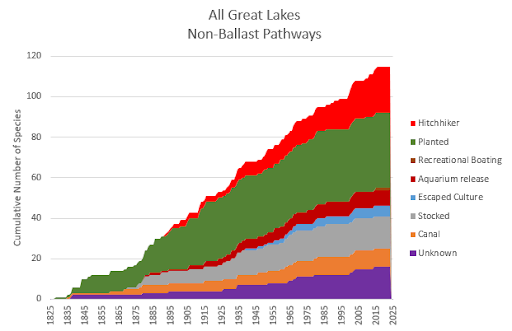

While ballast water has been a major way species have entered the Great Lakes, it hasn't been the only way.

When having conversations about aquatic invasive species in the Great Lakes region, most people are quick to blame ballast water when the talk turns to causes. Justifiably so, as ballast water historically has been responsible for more introductions of species to the Great Lakes than any other pathway. The introduction of zebra mussels to the Great Lakes in transoceanic ballast water and their subsequent widespread impacts to the region brought the issue of aquatic invasive species to public attention in a dramatic way, and the many species introduced by ballast water continue to live in the Great Lakes and impact both the ecosystem and human use to this day.

However, ballast water being the major pathway doesn’t mean it has been the only pathway. Historically, ballast water has been responsible for 40% of the introductions of established non-native species to the Great Lakes, and no new species have been introduced to the Great Lakes from ballast water since 2006. The major success of ballast water regulation in stopping new invasions by this pathway is discussed in the companion article "Balancing Act: A Policy Success Story in the Great Lakes." So what are the other pathways by which non-native species have entered, and continue to enter, the Great Lakes?

Planting

After ballast water, planting is the next largest vector (20%) for introduction of established non-native species in the Great Lakes. Deliberate planting of non-native aquatic plants has a long history in the region, with the first reports of wild (outside cultivation) common reed (Phragmites australis australis) in the Great Lakes basin going back to 1828. Among the recent planted invaders, water soldiers (Stratiotes aloides) escaped water gardens to establish wild populations in Canada’s Trent-Severn waterway in 2009 and marched downstream to reach Lake Ontario in 2021.

Stocking

Parallel to planting, deliberate stocking of non-native fishes and crayfishes has a long history in the Great Lakes region and is responsible for 8% of the overall introductions of non-native species to the Great Lakes. Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) were first stocked in the Great Lakes in 1870. Deliberate authorized stocking of new fish species has largely stopped in the Great Lakes, with the last species attributed to this pathway being smallmouth buffalo (Ictiobus bubalus) with the discovery of a reproducing population in Wisconsin in 1965 (likely introduced in a much earlier stocking).

Escaped culture

While the planting pathway included both organisms deliberately planted in the wild and those planted in gardens which later escaped, the stocking pathway was limited to just those deliberately stocked to natural waters. In parallel to garden/agricultural escaped plants is a pathway we call "escaped culture" – these creatures were being raised in contained systems with no intention of release, but accidentally got out into the natural environment. The red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) is one such species that is frequently in the news: these crustaceans were most likely brought into the Great Lakes region with the intent to serve them in a traditional ‘crawfish boil’ or other recipe.

Hitchhikers

The category ‘hitchhikers’ is used for species that weren’t themselves brought in deliberately, but came into the Great Lakes attached to another deliberately-introduced species (such as stocked fish or native and non-native plants). Hitchhikers are the third leading pathway (behind ballast and planting), responsible for 12% of established non-native species. Many hitchhikers are parasites, bacteria, and viruses which proved able to switch hosts to impact native species. Hitchhikers are responsible for most recent invasions, and are the only pathway of introduction showing an increasing rate. One recent hitchhiker is the eel swim bladder parasite (Anguillicola crassus), which was likely accidentally introduced with juvenile American eels deliberately translocated to the St. Lawrence River from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia between 2007 and 2010 in an effort to counteract declining native American eel populations in the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. Diploid grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) capable of reproduction were likely accidentally brought into the Great Lakes with supposedly sterile triploid grass carp being stocked for control of aquatic plants; reproducing populations of grass carp were identified in the western basin of Lake Erie in 2011. The gill maggot (Salmincola californiensis) was discovered in an eastern Lake Ontario tributary in 2014 and in the Lake Erie basin as early as the 1980s; although it had not been reported in regional hatchery stocks previously, it likely hitchhiked into the Great Lakes on rainbow trout stocks transported from the west coast. The non-native copepod Mesoscyclops pehpeiensis was originally introduced to North America as an experimental control for mosquitos in prawn aquaculture and ricefields to the south and likely hitchhiked with other water garden plants into the Great Lakes around 2016.

Recreational boating

More typically discussed in the context of controlling the spread of aquatic invasive species already established locally within the Great Lakes basin, recreational boating is also a growing pathway for new introductions to the Great Lakes. The non-native cladoceran Diaphanosoma fluviatile likely made the jump from the Mississippi River basin to the Great Lakes as a hitchhiker with recreational boat traffic (first Great Lakes report for the species was in 2015).

Aquarium release

Another pathway potentially on the rise following an increase in the hobby is release from aquariums. Recent examples include both aquatic plants like Hydrilla verticillata (first seen in the Great Lakes basin in 2000) as well as animals such as the marbled crayfish Procambarus virginalis, not yet established in the Great Lakes but found in an Ontario park just four miles from Lake Ontario in 2021. Learn more about marbled crayfish in the companion article “The Cloning Crayfish Conundrum.”

Canals

We tend to think of canals as a historic pathway for introduction of non-native species to the Great Lakes, and it is true that the last recorded introduction to the Great Lakes attributed to a canal introduction was the blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis) in 1981. But many canals built long ago remain open and active in the Great Lakes region, which could remain an open door for invasive species to move from adjacent watersheds such as the Mississippi and Hudson into the Great Lakes.

To learn more about these or other Great Lakes aquatic invasive species, visit the Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS).

While ballast regulations have been truly remarkable in reducing new invasions to the Great Lakes, future progress in preventing the introduction of new species will require that regulators, managers and the public widen our focus to increase vigilance and address these ‘less traveled’ pathways.

Additional resources

Additional resources for those wishing to take action to address some of these pathways include:

- Reduce Invasive Pet and Plant Escapes (RIPPLE) - https://www.canr.msu.edu/invasive_species/ripple/index

- USFWS Voluntary Guidelines for Recreational Activities - https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Voluntary-Guidelines-Preventing-Spread-ANS-Recreational.pdf

- USFWS Classroom Guidelines - https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ANSTF-Classroom-Guidelines-Final.pdf

- Stop Aquatic Hitchhikers - https://stopaquatichitchhikers.org/

- Don’t Let it Loose - https://www.dontletitloose.com/

- Habitattitude - https://www.habitattitude.net/

Please also see the companion article “Foes or Food: Foraging for Great Lakes Invasive Species.”

Michigan Sea Grant helps to foster economic growth and protect Michigan’s coastal, Great Lakes resources through education, research and outreach. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University and its MSU Extension, Michigan Sea Grant is part of the NOAA-National Sea Grant network of 34 university-based programs.

This article was prepared by Michigan Sea Grant under award NA22OAR4170084 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce through the Regents of the University of Michigan. The statement, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce, or the Regents of the University of Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email