Save the umbrella for a rainy day: an alternative way forward for conservation

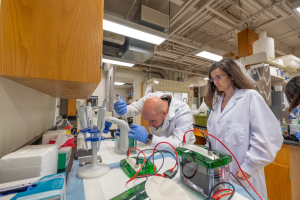

PhD student and EEB Digital Fellow Beth Gerstner explores new ways to shape conservation beyond the cute and fuzzy

Beth Gerstner is a PhD student in the department of fisheries and wildlife, and a Digital Fellow in the Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior Program.

Popular conservation campaigns featuring mammals with big eyes and fuzzy features implies that to be saved, an animal best be cute.

Yet species less well known and not as visually pleasing have essential roles within our ecosystems and are sometimes left out of critical assessments of our world’s biodiversity.

This is due to the high uncertainty about their conservation status and potential threats. A 2015 study in Biological Conservation showed that the omission of these species can lead to an underestimate of biodiversity and misappropriation of conservation programs to certain areas. Faculty at MSU's Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior program indicates that a focus on species providing ecosystem services may be the way forward to increase inclusivity for these important and lesser known creatures.

“We need to focus on maintaining healthy ecosystem function. Without healthy ecosystems, the many services that humans and nature rely on will be in jeopardy, including clean water, pollination, nutrient cycling, healthy fisheries, and many others,” said Phoebe Zarnetske, associate professor in the MSU Department of Integrative Biology. “Unfortunately, these services are already in jeopardy in many regions of the world.”

Conservation campaigns meant to raise funds and public awareness, such as the World Wildlife Fund campaign for pandas, are lucrative and can help save habitat for the charismatic flagship species, with the intention of that focal species serving as an umbrella of protection for other species sharing the same habitat.

However, the Biological Conservation story co-authored by MSU’s Jianguo "Jack" Liu and then-PhD student Thomas Conner, showed that the umbrella approach for panda conservation did not adequately protect all species with overlapping ranges after taking habitat loss and degradation into consideration. This is a likely reality for many species sheltered under the “umbrella” of a flagship species’ protection and can lead to issues with the long term success of this approach.

Additionally, this focus on charismatic species can lead the public to believe that these critters are the only kinds of animals worth saving. One of the downfalls of the flagship umbrella approach is that species are chosen based solely upon their appeal to a wide audience. However, many species play integral roles in ecosystems, provide humans with crucial services, and need to be prioritized for conservation. Think bees for pollination, bats and lady beetles for pest control, birds and bats for seed dispersal.

Zarnetske suggests an alternative approach to choosing which species should receive priority for conservation efforts - one based not on their looks but on their roles within an ecosystem.

“The main advantage to using species’ functional roles to prioritize conservation efforts is that species’ functions align more directly with ecosystem functions and services—such as nutrient cycling and pollination—which are necessary for humans and nature alike,” said Zarnetske, whose research focuses on community ecology and the impact of climate change across scales.

“These functions and services affect many species, not just a particular focal species, and so focusing on a suite of species and their particular traits involved in providing the functions and services can more effectively conserve a much wider array of species.” For example, focusing on conserving animals which spread seeds, and thus preserve long-term forest survival.

While this alternative approach has the potential to protect a wider range of species, it is not without complication. As Zarnetske points out, “A disadvantage to focusing on species’ functional roles to prioritize conservation is that we lack this basic information for some of the more rare or lesser-known species”.

Many of the world’s species suffer from this lack of in-depth knowledge about their geographical range limits, population dynamics, habits, and threats needed to truly understand their conservation status, which has slowed our progress in fully understanding the important roles these less charismatic organisms play in our ecosystems.

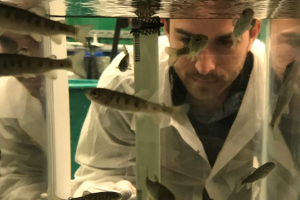

Douglas Landis, a University Distinguished Professor in Entomology, whose lab focuses on the conservation and management of insects in both natural and managed landscapes, is currently working on a project focused on micro-arthropods, largely mites and springtails. His lab studies their ecological role in shredding litter and turning that into soil, and also in regulating the microbes turning that litter and carbon into more secure organic matter– an important service for the success of bioenergy crop production.

When thinking about the vast diversity of critters living in the soil, he said, “We haven’t even given names to these species yet and without that it’s hard to study them and know their conservation status. There’s probably tens of thousands and we have a fraction of them studied to the point where we can identify them”.

Some species lack formal descriptions, while others lack any sort of data. However, there is much ongoing research aimed at trying to fill this gap. With digitization of museum and herbarium records becoming increasingly common along with more field studies, more data, including range and trait information, are becoming available for these species. These resources will become invaluable for our understanding of species roles in ecosystems, their services, and how best to conserve them.

If the flagship umbrella approach to conservation masks the need for attention on other important, if less charismatic species, it’s still an important tool to raise awareness and funding for conservation initiatives. Gary Roloff, professor and chair of the department of fisheries and wildlife, thinks a hybrid approach might be the way forward.

“It seems that the public have low tolerance for information with ‘too much detail’, so trying to rally folks behind a concept like ecosystem services might be a stretch,” Roloff said. “Put a photo of a panda bear and a wetland on Instagram and see which gets more ‘likes’; panda will win every time. I think we can effectively use charismatic species to further the conservation causes associated with ecosystem service.”

Print

Print Email

Email