You are closer to the Great Lakes than you think

Trace your potential impacts on water resources by visualizing how water flows from your local area and throughout the Great Lakes Basin.

All water is interconnected and a single chemical spill into a Michigan river has the potential to affect the Great Lakes. This is because every Michigan watershed (also called a catchment or drainage basin) ultimately is connected to the Great Lakes.

A watershed is an area of land that catches rain and snow and drains or seeps it downward into a common body of water such as a river, stream, ocean, lake or pond. Watersheds may cover only a few acres or encompass millions of square miles. Watersheds are irregularly-shaped and separated from each other by ridges and high points. They respect no human boundaries— watersheds cross local, county, state and even international borders. Water that enters a small stream, which is part of a small watershed, will eventually flow into a larger river with a larger watershed. The small stream’s watershed is a subwatershed of the larger river’s watershed.

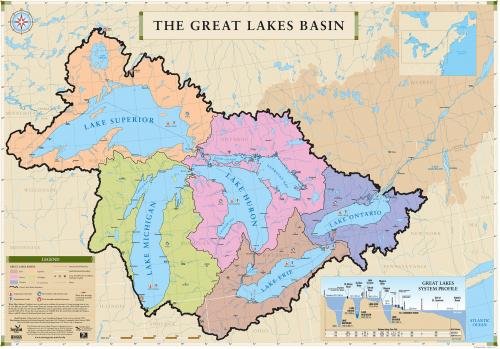

In Michigan, virtually all watersheds eventually drain into one of the Great Lakes, which are part of what is called the Great Lakes Basin (Figure 1, below). As its name implies, the Lake Superior watershed drains to its common body of water, Lake Superior. Similarly, the Lake Michigan watershed drains to Lake Michigan. Geographically, these two Great Lakes connect to each other and to Lake Huron. Lake Huron connects to the St. Clair River, which connects to Lake St. Clair, then the Detroit River, then Lake Erie, then the Niagara River, then Lake Ontario, then the Gulf of St. Lawrence and finally with the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 1: The Great Lakes Basin connects Michigan’s watersheds to the St. Lawrence Seaway. Photo Credit: Michigan Sea Grant.

Consider a smaller-scale watershed example. The Red Cedar River watershed (Figure 2, below) is a subwatershed of the larger Grand River Watershed. The Red Cedar River originates in Livingston County and flows north and west for about 50 miles until it enters the Grand River in Ingham County. An event, such as an oil spill in the Red Cedar River, has the potential to flow to and affect the Grand River, which drains into Lake Michigan, and as explained earlier, eventually into the Atlantic Ocean. Even if you don’t live in the Red Cedar River or Grand River watershed, consider finding out what watershed you are a part of, and how your actions can impact the Great Lakes.

Figure 2: A map of the watersheds around Michigan State University that drain to the Grand River and eventually into Lake Michigan. The inset shows where this land area is situated in Michigan. Photo Credit: Institute of Water Research, Michigan State University.

What happens on your property can affect an entire watershed and beyond with the potential to have a profound impact on our collective water resources because of the way they all are connected through the water cycle. The Great Lakes Basin serves as a perfect example of how impacts in one area can be felt watershed-wide. The next time you use fertilizers or pesticides or wash the car in your driveway, consider how this may affect the lake you live on or the water you drink.

For more information about Michigan Watersheds, read the article, “An understanding of Michigan Watersheds is critical to understanding how our actions influence water quality of the Great Lakes and beyond” published by Michigan State University Extension, as well as “Homes defines the Great Lakes Region.” For more information about Michigan’s watersheds, review the Michigan Sea Grant publication, “An Introduction to Michigan Watersheds” The Michigan Sea Grant also has additional information on The Great Lakes Region.

Print

Print Email

Email