FINAL REPORT: Baseline Value Chain Assessment for Key Legume Markets in West Africa

Legume Systems Research Innovation Lab – Commissioned Activity Final Report

Project Title: Baseline Value Chain Assessment for Key Legume Markets in West Africa

Principal Investigator:

Michael Olabisi (PhD)

Michigan State University

co-Principal Investigator:

Mywish Maredia (Prof.)

Michigan State University

Locations:

Kano, Nigeria

Niamey, Niger

Ilorin, Nigeria

- Executive Summary

To support future research initiatives on legume value chains in West Africa, we conducted a targeted survey in three large cities in or near the West African Sahel region –Kano and Ilorin in Nigeria, and Niamey in Niger. The in-depth assessments of the three market hubs also serve as a baseline for future studies of agricultural markets in this sub-region.

The surveys documented key actors and locations -- through the buyer-supplier relationships from farmers to consumers along the legume value chains. The surveys show that market linkages run deep into production areas from the main markets, and that the actors are predominantly male, and older than the average person. By mapping the links from producers to intermediaries, and ultimately to consumers, the baseline assessment supports future work by researchers and policymakers to identify gaps in market linkages, and the pattern of buyer-supplier relationships in the supply chain.

- Project Partners

Our West-Africa based research partners are:

Dr. Toyin Ajibade at the University of Ilorin,

Dr. Hakeem Ajeigbe at International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) Nigeria. He is also affiliated with the Center for Dryland Agriculture. Bayero University in Kano.

Dr. Abdoulaye Djido of the Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey. He left the university toward the end of the project for another research organization.

- Project Goals and Objectives

The main objective of the project is to provide a baseline study of key legume markets in West Africa, and their linkages. Having this baseline study at three strategic locations will provide valuable insights and a broad geographic coverage to understand legume markets and value chains in major legume producing areas in West Africa. The insights are to support other efforts leading to a resilient and well-functioning value chain/market system, which is critical for farmers to generate income and earn livelihoods, and for consumers to access agricultural products.

Information about market linkages has great potential for mitigating the effects of events that may disrupt the flow of food from producers to final consumers. The project serves primarily as an assessment of how the market works, to support policymakers who wish to identify points of intervention to maintain the resilience of the food value chain. The assessment is also to help future research initiatives on legumes value chains in West Africa and other locations.

- Overview of Activities

Our team surveyed 1,725 stakeholders in the legume chain, based in and around our worksites in Niger (Niamey), and Nigeria (llorin and Kano). Kano is the largest city in the West and Central African Sahel. The Kano metro area also hosts one of the largest grain markets in West Africa, with links to many of the agricultural producers in the region – not just in Nigeria. The Ilorin metro area is a major link point between agricultural producers of Northern Nigeria and the agricultural markets of Lagos -- Africa’s largest city, in addition to other large markets for legumes in the populous cities of Southern Nigeria. Niamey is a centrally located West African city, a potential hub for connecting the Sahelian population centers of Sokoto and Kano, in Nigeria, Zinder and Maradi in Niger, to markets as far as Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, and to farms in rural Niger, Benin Republic and Nigeria. The commissioned study conducted at three strategic locations provides broad geographic coverage to understand legume markets and value chains at the center of the largest cowpea producing area in Africa. All three worksite locations are in areas that are considered food security hot-spots, or that are directly linked to the hot-spots through the legumes value chain.

- Accomplishments and Main Findings

Table 1 shows stakeholders surveyed in the value chain, organized by their roles. Respondents who identified primarily as producers were coded as farmers. We defined resellers as those who did not identify primarily as retailers, and who purchased and re-sold legumes to others in the value chain.

Table 1: Stakeholders by Role

|

Role in Value Chain |

Number Surveyed |

|

Farmer |

648 |

|

Reseller |

398 |

|

Retailer |

679 |

The largest set of stakeholders interviewed were from the Ilorin worksite (760), with smaller numbers from Kano (672) and Niamey (293). The numbers by location reflects our methodology, which was to conduct a census of all legume sellers at a point in time in the largest market areas for our worksites, and to use a snowball sampling technique to locate their partners in the value-chain, until we interview the farmers that produce the grain. Niamey represented a smaller population, while Ilorin had both large numbers of farmers, and resellers represented in the data. The attributes of the stakeholders interviewed, is informative for policy.

The first notable differences between the stakeholder roles (and locations) is the gender-split. Few women engaged in the value-chain in Kano (1%) and Niamey (7%), while Ilorin (25%) was more gender-balanced.

Table 2 shows that farmers and re-sellers are predominantly male. About 20% of retailers are female. This is where our survey captured the highest level of female participation in the value-chain. Notably, 111 of the 135 female retailers came from the Ilorin worksite, where there were more female than male retailers (79).

Table 2: Stakeholders by Gender (and Role)

|

Role in Value Chain |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

Farmer |

585 (90%) |

63 (10%) |

648 |

|

Reseller |

368 (92%) |

27 (7%) |

398 |

|

Retailer |

542 (80%) |

135 (20%) |

679 |

*Gender data was missing for 5 respondents.

The differences by gender participation are remarkable for at least two reasons. First, farming and the role of linking farmers to retailers appear to be primarily male, across all locations. This pattern may be linked to cultural differences related to the production of a cash crop like cowpea, and the gender associated with the production of cash crops. See for example, that the female share of farmers in Ilorin is 13%, compared with 1% for Kano. The re-sellers who undertake the buying from farms to supply retailers follow a similar pattern. Second, even for retailing, where women are most represented, the representation is more notable in Ilorin, where they are 58% of retailers, compared to Niamey (10%) and Kano (1.4%).

The youth (defined here as persons age 25 and younger), represented almost 10% of the stakeholders we interviewed. The low percentage of youth is in part unsurprising, give the experience and capital needed to participate in the value chain. Farmers need land, re-sellers need extensive social connections and capital, and retailers need sufficient funds to support the costs of their inventory. Furthermore, the physical low-tech labor required for farming is not particularly attractive to most youth.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that no youth showed up in our sample of farmers for Kano, and the share of farmers in the youth category was 8%. Similarly, for the capital-intensive role of reseller, the share of youth was 5%. Finally, the number of retailers aged 25 and below represented 14%, which fits the expectations. The attributes of the stakeholders for example, can inform the types of outreach needed to share information with participants in the value – especially when the information needs to be conveyed by people to whom the farmers and traders in the value chain can relate.

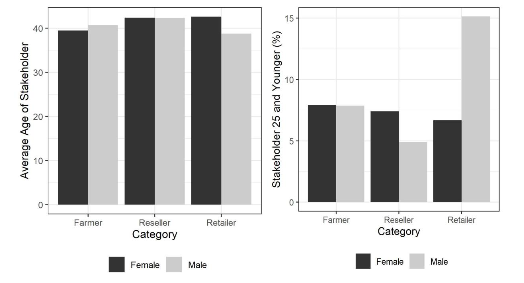

Figure 1 further highlights the age differences between different parts of the value chain. The first panel of the Figure shows that resellers are the oldest group in the value-chain on average, with 42.3 years for the male and female participants at that stage. Female retailers (42.6) are older on average than male retailers (40.7 years).

Figure 1: Age by Role in Value Chain (and Gender)

The second panel of the Figure goes beyond averages to show that the greatest level of youth participation is in the retail sector (primarily) by men. While about 7.9% of male and female farmers are aged 25 or younger, that share for female participants falls to 7.4% and 6.6% for the reseller and farmer stages in the value-chain.

The differences are also linked to location for farmers and resellers. The shares of retailers aged 25 or younger are respectively, Kano (12%), Niamey (17%) and Ilorin (13%). By comparison, the shares of resellers age 25 or younger are, Kano (15%), Niamey (5%) and Ilorin (4%). The stark difference between Kano and other locations suggests that access to capital and the other requirements of the reseller role varies significantly between the locations.

One reason for our interest in value chains for this commissioned activity, is to understand how information or the adoption of technologies can propagate through the value chain.

We find that supply chain linkages are deep, with the largest cities sourcing food from hundreds of miles away. Cities as far away as Salka (360 miles), and Gombe (240 miles) supply legumes to the Kano market. Therefore, information can pass from key actors in Kano to these more remote locations. Similarly, markets as far away as Zinder, and farms in Gaya, more than 200 miles away are linked to the markets in Niamey. International trade is a small portion of the supply for Kano –

the relatively small scale of international trade is one of the motivations for the trade integration project proposed to the Legume Systems Innovation Lab.

We also find that cowpea dominate the market. The white and brown varieties of cowpea are the only legumes (other than soybean or peanut) that most consumers buy in the area. The white variety is prevalent all locations, but the brown variety is more popular in Ilorin than in either Kano or Niamey. In part due to the linkages between the markets, the brown variety is being sold by more retailers in Kano and Niamey than in previous years. From our survey, here is the share of retailers at each worksite that sold the white cowpea variety: Kano (97%) Niamey (94%) Ilorin (98%). By comparison, the share of retailers selling the brown variety was: Kano (45%) Niamey (68%) Ilorin (96%). Retailers selling at least one of the two represented 98% of our sample.

In exploring how information can be passed through the value chain, we explore the reported linkages between retailers and re-sellers. We observe that large retailers and suppliers tend to have links to partners in the value chain that stretch over greater distances. That said, much of the trading relationships are local, and resellers play a large role in bridging the farms and farm-gate markets to the large urban markets that serve consumers. As expected, much of how the markets work is driven by context. Large cities have large markets.

6. Utilization of Research Outputs

The market surveys from the proposed commissioned activity provided a vital starting step for our current research initiatives on using mobile technology to integrate legumes value chains across West Africa. Working on the project also created opportunities for capacity-building with West-Africa based research partners at the University of Ilorin, Bayero University in Kano and the Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey. It also created the opportunities to identify and work with the stakeholders who have supported the trade integration project.

The survey data and the patterns reported above are also valuable as a tool for future work on legume and other agricultural markets in West Africa. The pattern of buyer-supplier relationships, and the disparities along gender and age-group lines can be useful as benchmark for other regions where there is a need to understand and plan for the resilience of food value chains.

7. Further Challenges and Opportunities

Legume markets in West Africa have suffered from low levels of trade integration for decades. Therefore, we have missed opportunities that include higher levels of food security, and greater income of the participants in value chains. One well documented opportunity relates to moving legumes across borders in the region in response to seasonal differences between countries, if we can promote linkages between markets that do not currently trade (or trade much).

The linkage between markets documented in our study, as well as the composition of actors in the value chain also indicate opportunities for the inclusion of youth and women in the value chains. Technology is one possibility for bridging this gap.

One challenge and opportunity derived from this project, is extending the current work from the three large cities in the commissioned activity to other cities that could be crucial to food security in the region.

Print

Print Email

Email