Statewide Ballot Proposal 22-2: Promote the Vote 2022

DOWNLOADOctober 11, 2022 - Eric Walcott, Michigan State University Extension

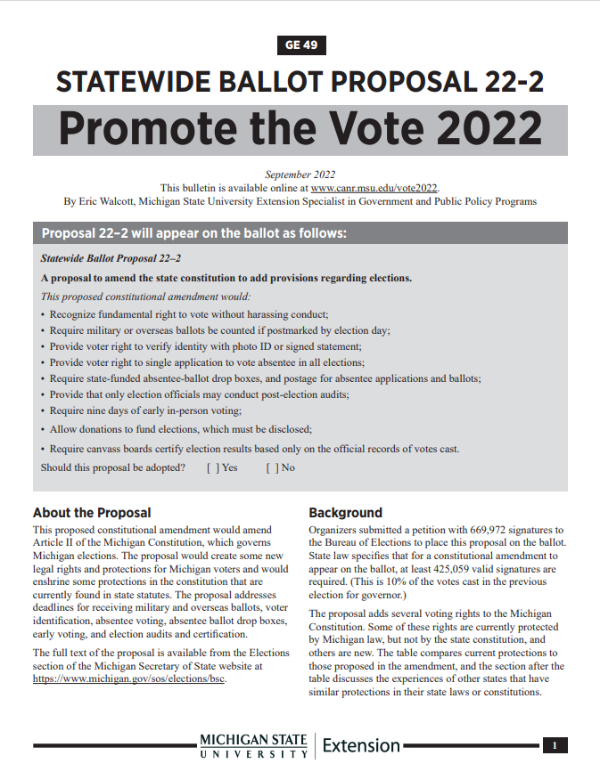

Proposal 22–2 will appear on the ballot as follows:

Statewide Ballot Proposal 22–2

A proposal to amend the state constitution to add provisions regarding elections.

This proposed constitutional amendment would:

- Recognize fundamental right to vote without harassing conduct;

- Require military or overseas ballots be counted if postmarked by election day;

- Provide voter right to verify identity with photo ID or signed statement;

- Provide voter right to single application to vote absentee in all elections;

- Require state-funded absentee-ballot drop boxes, and postage for absentee applications and ballots;

- Provide that only election officials may conduct post-election audits;

- Require nine days of early in-person voting;

- Allow donations to fund elections, which must be disclosed;

- Require canvass boards certify election results based only on the official records of votes cast.

Should this proposal be adopted? [ ] Yes [ ] No

About the Proposal

This proposed constitutional amendment would amend Article II of the Michigan Constitution, which governs Michigan elections. The proposal would create some new legal rights and protections for Michigan voters and would enshrine some protections in the constitution that are currently found in state statutes. The proposal addresses deadlines for receiving military and overseas ballots, voter identification, absentee voting, absentee ballot drop boxes, early voting, and election audits and certification.

The full text of the proposal is available from the Elections section of the Michigan Secretary of State website at https://www.michigan.gov/sos/elections/bsc.

Background

Organizers submitted a petition with 669,972 signatures to the Bureau of Elections to place this proposal on the ballot. State law specifies that for a constitutional amendment to appear on the ballot, at least 425,059 valid signatures are required. (This is 10% of the votes cast in the previous election for governor.)

The proposal adds several voting rights to the Michigan Constitution. Some of these rights are currently protected by Michigan law, but not by the state constitution, and others are new. The table compares current protections to those proposed in the amendment, and the section after the table discusses the experiences of other states that have similar protections in their state laws or constitutions.

Table: Comparison of current Michigan law to the proposed amendment to the Michigan Constitution.

|

Issue |

Current Michigan Law |

Proposed Constitutional Amendment |

|

Military or overseas ballots |

Constitutional right to have an absent voter ballot sent to them at least 45 days before an election upon application (Article II, § 4). |

Require that absentee votes be counted if the envelope is postmarked by Election Day and received within six days after the election. |

|

Voter ID |

State law requires voters to either show picture identification or sign an affidavit attesting to their identity (MCL 168.523). |

Would codify existing law in the state constitution. |

|

Absentee voting |

Constitutional right to vote absentee without giving a reason. Voters must fill out absent voter applications for each election (Article II, § 4). Voters must pay postage if mailing in absentee ballots. |

Voters may request an absentee ballot be mailed to them for all future elections. State-funded prepaid postage would be included with absentee ballot applications and absentee ballots. |

|

Ballot drop boxes |

State law doesn’t require but does regulate the use of ballot drop boxes (MCL 168.761d). |

Would require at least one state-funded drop box for every municipality, and at least one for every 15,000 voters in municipalities with more than 15,000 voters, accessible 24/7 for 40 days before each election and until 8 p.m. on election day. |

|

Absentee ballot tracking |

State law requires that if cities or townships have access to the state ballot tracker program, their clerks must use it and allow voters to track their votes online (MCL 168.764c). |

Would require use of a state-funded system to track submitted absent voter applications and absentee ballots. Would give voters the option to receive notifications about the status of applications and ballots, be informed of deficiencies, and receive instructions for addressing deficiencies. |

|

Early voting |

State law allows early voting in the form of completing absentee ballot at local clerk’s office (Article II, § 4). |

Would require a minimum of nine days of in-person early voting for all statewide and federal elections, from the second Saturday before to the Sunday before an election. Early voting sites must be open for at least 8 hours each day of early voting. Election officials may add additional early voting days at their discretion. |

|

Certifying elections |

State law requires the Board of State Canvassers or boards of county canvassers to determine which candidate has received the greatest number of votes and declare that candidate the winner (MCL 168.171). |

Would require election results to be certified based on the official record of votes cast and clarify that the Board of State Canvassers is the only body authorized to certify elections for statewide or federal offices. |

|

Post-election audits |

State constitution protects right to audit of statewide elections (Article 2, § 4[h]). State law requires secretary of state to conduct election audits of randomly selected precincts after each election (MCL 168.31a). |

Would require the secretary of state to conduct election audits and supervise and direct county officials in conducting audits. Would forbid officers or members of the governing body of a political party and precinct delegates from having any role in an election audit. All audits would be required to be conducted in public following methods finalized before the election. |

|

Election funding |

State law doesn’t address donations to fund elections. |

Would allow local units of government to accept publicly disclosed charitable donations and in-kind contributions to conduct and administer elections. |

From State Law to the State Constitution

This proposal would add several new election-related protections to the Michigan Constitution. It would also enshrine parts of several existing state elections laws there. You may wonder why anyone feels the need to add something that is already addressed in state law to the state constitution.

The answer is that it is harder to change the state constitution than it is to change state statutes or laws. State laws can be approved with simple majority votes in the State House of Representatives and State Senate, followed by the governor’s signature, while the state constitution can only be amended by a vote of the people. Proposed amendments are placed on the ballot either through voter-initiated petition drives (as this proposal was) or by two-thirds votes of both houses of the state legislature.

As a result of these differing degrees of difficulty, hundreds of laws are passed each year in Michigan, but only 36 constitutional amendments have been approved since the state’s current constitution was adopted in 1963.

Comparing Michigan to Other States

The proposed constitutional amendment deals with a number of topics related to voting. In considering what these changes may mean for Michigan, it can be helpful to consider how other states handle these issues.

Absentee Voting

Five states (Arizona, Maryland, Montana, New Jersey, and Virginia) and Washington, D.C., currently allow any voter to join a permanent absentee ballot list and receive absentee ballots for all future elections. If this proposal is adopted, Michigan would join that group in allowing permanent absentee voting (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022c).

Eight other states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, and Washington) allow all elections to be conducted by mail, and automatically mail ballots to all registered voters for each election (NCSL, 2022e).

Voter Identification

State voter identification laws vary by type (voter ID and non-voter ID) and strictness (MIT Election Data + Science Lab, 2021a; & NCSL, 2022f).

- Voter ID States—Thirty-five states require voters to present some form of identification at the polls. Eighteen of these require photo ID (such as a driver’s license or state ID card) and 17 will accept either photo or non-photo ID. The 12 strictest voter ID states require voters who show up at the polls without acceptable ID to vote provisional ballots. For a provisional ballot to be counted, the voter must take additional steps after election day to prove their identity, such as presenting their ID at the local clerk’s office. Michigan requires voters to present photo ID at the polls but will allow voters without it to sign an affidavit of identity.

- Non-Voter ID States—Fifteen states use other methods of verifying a voter’s identity at the polls, such as matching the voter’s signature with one kept on file with the election office.

Early Voting

Twenty states allow some form of in-person early voting, as do Washington, D.C., American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Early voting periods range from three to 46 days (the average is 23 days). The proposed amendment would require at least nine days of early in-person voting in Michigan.

States begin early in-person voting as early as 55 days before and as late as the Friday before an election (the average start date is 30 days before). This proposal would require early voting to begin in Michigan at least 11 days before an election and end on the Sunday before it (NCSL, 2022a).

Ballot Drop Boxes

Michigan doesn’t require the use of ballot drop boxes, but is one of 23 states with laws governing their use. Other states allow the use of drop boxes at the discretion of local officials, without specific statutes about their use. Nine states currently have laws requiring ballot drop boxes. The requirements vary, with some states requiring a certain number of drop boxes per county and others setting requirements based on population per municipality (NCSL, 2022d).

Election Certification and Audits

Thirty-four states, including Michigan, currently require what are known as traditional post-election audits. These audits look at a specific percentage of voting districts and compare paper records to the results produced by the voting systems. In traditional audits, the same number of ballots are reviewed regardless of the margins of victory in particular races. Fifteen states, again including Michigan, have adopted what are called risk-limiting audits. Such audits use statistical principles and methods and are designed to limit the risk of certifying an incorrect election outcome. In races with large margins, fewer ballots need to be audited, while in tighter races, more ballots need to be audited (NCSL, 2022b).

The proposed amendment would not significantly change the audit process in Michigan except to clarify, in the constitution rather than in state statute, that the secretary of state oversees all election audits, members of governing boards of political parties may not participate in audits, and audits must be conducted according to procedures confirmed before the election was held that is being audited.

Potential Impacts

The most common questions about early voting, absentee voting, and voter identification laws are whether an increase in absentee voting or voting by mail leads to an increase in voter fraud, and whether stricter voter identification laws prevent voter fraud, respectively. A summary of research and links to more information on both questions follows.

Voting by Mail

The history of voting by mail (also called absentee voting) in the United States dates to the Civil War, when Union and Confederate soldiers cast votes from the battlefield that were counted back home. Laws passed since the late 1800s have, in many cases, increased access to voting by mail (MIT Election Data + Science Lab, 2021b). The popularity of voting by mail has steadily increased over time. In 2016 about 21% of votes in the U.S. were cast by mail, and by 2020 this number had risen to 43%. (The COVID-19 pandemic contributed greatly to this increase [Scherer, 2021]).

No evidence supports the ongoing assertions that voting by mail is more susceptible to fraud than in-person voting. According to the Heritage Foundation (2022), only 248 cases of “Fraudulent Use of Absentee Ballots” have been recorded since 1988. Over that same 34-year period, about 3 billion votes have been cast in federal elections alone (Federal Elections Commission, n.d.).

Michigan, like all other states, takes multiple steps to ensure the security of absentee ballots, including verifying signatures on absentee ballot applications and absentee ballots and verifying voter information and eligibility against voter registration records. The following resources offer more information on absentee voting security:

- “Here’s how Michigan ensures your absentee ballot is secure” (https://bit.ly/3RKxl0L)

- Mail ballot security features: A primer (https://bit.ly/3xqlrky)

- How does vote-by-mail work and does it increase election fraud? (https://brook.gs/3dbBxYo)

Multiple studies suggest that voting by mail changes how a large percentage of registered voters cast their votes (with greater access to vote by mail, more people vote by mail), but research shows voting by mail has only a modest impact on total voter turnout. Some studies show an increase of 2% to 4% in total turnout after the adoption of vote by mail (Gerber, Huber, & Hill, 2013).

Other studies show that voting by mail gives neither party an advantage (Thompson, Wu, Yoder, & Hall, 2020). For example, Stewart (2020) showed that while a greater share of Democrats (59%) than Republicans (30%) cast their ballots by mail in 2020, this did not result in an overall greater increase in voter turnout for Democrats. Turnout spiked that year for both Democrat and Republican voting groups (Frey, 2021) as Americans turned out to vote in record numbers (Desilver, 2021).

Voter Identification

The most common claims for strict voter ID laws are that such laws will increase election integrity by reducing voter fraud. Extensive research has shown that, rather than reducing voter fraud, voter ID laws have no impact on it (Cantoni & Pons, 2021). Such laws also fail to increase confidence in election integrity (Ansolabehere & Persily, 2008; Stewart, Ansolabehere, & Persily, 2016).

The most common claims against strict voter ID laws are that they disenfranchise minority voters and other disadvantaged populations. Research on the impact of strict voter ID laws on turnout has been varied. Some studies have shown that these laws have no impact on voter turnout, while others have shown they have a negative impact. One explanation for why strict voter ID laws don’t uniformly suppress voter turnout is that they often motivate efforts to encourage turnout among the populations they target. So in the end, even if strict voter ID laws ultimately fail to suppress turnout, they succeed in placing an extra burden on certain groups of voters (MIT Election Data + Science Lab, 2021a).

Summary

The proposed constitutional amendment would make changes to the way Michigan conducts elections, increasing access to voting by mail and ballot drop boxes, extending the period for military and overseas ballots to be returned, adding early in-person voting, and allowing local units of government to accept donations to fund elections. For the most part, these changes mirror practices currently in place in many other states. On other topics, the proposal would not change existing practice, but would codify existing law in the state constitution.

References

Ansolabehere, S., & Persily, N. (2008). Vote fraud in the eye of the beholder: The role of public opinion in the challenge to voter identification requirements (pdf). Harvard Law Review, (121)7. 1737-1774. https://bit.ly/3AAQryT

Cantoni, E., & Pons, V. (2021). Strict ID laws don’t stop voters: Evidence from a U.S. nationwide panel, 2008–2018. Quarterly Journal of Economics, (136)4, 2615–2660. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjab019

Desilver, D. (2021). Turnout soared in 2020 as nearly two-thirds of eligible U.S. voters cast ballots for president. Pew Research Center. https://pewrsr.ch/3RkweUI

Federal Elections Commission. (n.d.). Election and voting information. https://bit.ly/3eVAhZy

Frey, W. H. (2021). Turnout in 2020 election spiked among both Democratic and Republican voting groups, new census data shows. The Brookings Institution. https://brook.gs/3eaUpGY

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., & Hill, S. J. (2013). Identifying the effect of all-mail elections on turnout: Staggered reform in the evergreen state. Political Science Research and Methods, 1(1), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2013.5

Heritage Foundation (The). (2022). Election fraud cases. https://herit.ag/2EIQ2yE

MIT Election Data + Science Lab. (2021a). Voter identification. https://bit.ly/3Rkw3c4

MIT Election Data + Science Lab. (2021b). Voting by mail and absentee voting. https://bit.ly/3pZzJEA

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022a). Early in-person voting. https://bit.ly/3e6XDLy

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022b). Post-election audits. https://bit.ly/3KBhCxW

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022c). Table 3: States with permanent absentee voting lists. In Voting Outside the Polling Place. https://bit.ly/3R4LNQN

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022d). Table 9: Ballot drop box laws. In Voting Outside the Polling Place. https://bit.ly/3CGPp7f

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022e). Table 18: States with all-mail elections. In Voting Outside the Polling Place. https://bit.ly/3Q3ZVs3

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2022f). Voter ID laws. https://bit.ly/3ctCY44

Scherer, Z. (2021). What methods did people use to vote in the 2020 election? U.S. Census Bureau. https://bit.ly/3e9J4XH

Stewart, C. (2020). How we voted in 2020: A first look at the survey of the performance of American elections (version 0.1; pdf). MIT Election Data + Science Lab. https://bit.ly/3ACGWix

Stewart, C., Ansolabehere, S., & Persily, N. (2016). Revisiting public opinion on voter identification and voter fraud in an era of increasing partisan polarization (pdf). Stanford Law Review, 68(6), 1455–1489. https://stanford.io/3AAHmWN

Thompson, D. M., Wu, J. A., Yoder, J., & Hall, A. B. (2020). Universal vote-by-mail has no impact on partisan turnout or vote share. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(25), 14052–14056. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2007249117

Print

Print Email

Email