What You Need to Know About Michigan’s Ticks

DOWNLOADJuly 25, 2025 - Paige Alexander, Jean Tsao and Deborah McCullough, Michigan State University Extension

Overview: What are Ticks?

Learn what to expect when entering a forest, methods of tick identification, ways to avoid tick bites, as well as information on Lyme Disease.

Imagine the most dangerous things in the forest. Initially, you may think of big predators such as bears or perhaps a pack of wolves. These fears are certainly valid; however, focusing on these predators may cause you to ignore a more inconspicuous danger: Ticks! Some ticks are the size of a sesame seed and thus are easily overlooked. Despite their small size, they can be one of the most dangerous creatures to encounter in the forest. Tick bites can lead to a multitude of diseases, such as Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. These typically cause fever, headache, chills and muscle aches or worse. Tick ranges continue to expand in the United States; now is the time to educate yourself about these detrimental pests.

Ticks

Contrary to popular belief, ticks are not insects. These tiny menaces are actually arachnids. Key differences include the number of legs and lack of wings. Insects have six legs and most have wings as adults, while nymphal and adult ticks have eight legs, no wings and are more closely related to spiders. Ticks are blood-feeding arthropods with around 900 described species representing 17 genera and three families, with a worldwide distribution. Ticks are obligate hematophagous ectoparasites, meaning they remain on the outside of the host’s body and feed on the blood of the host (e.g., mammals, birds or reptiles).

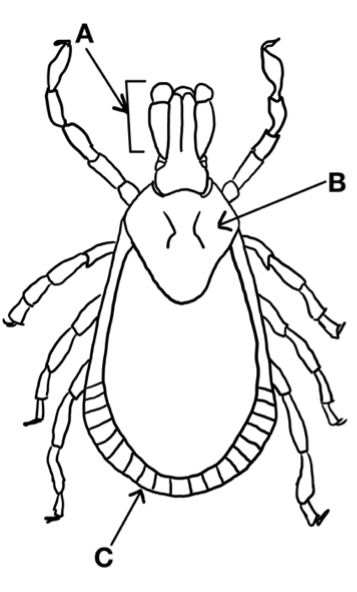

Hard (Ixodid) Tick versus Soft (Argasid) Tick

Ticks can be broadly separated into two groups: the Ixodid ticks, known as hard ticks and the Argasid ticks, known as soft ticks. As the names imply, the key difference between the two groups is presence of the hard plate, called a scutum, on the dorsal side (back) of the hard ticks. Soft ticks lack this plate. Soft ticks resemble small, wrinkled raisins and the mouth parts of soft ticks are not visible from above. Hard ticks are normally more mobile (aside from those that have a one-host life cycle) and engage in hunting and/or ambush behaviors while soft body ticks tend to stay close to the area they stay in the nests or burrows where they had hatched. Although both types of ticks are disease vectors, because they generally have a greater chance of contacting people, hard ticks are often considered of greater global medical importance.

Basic Tick Life Cycle

The basic life cycle of ticks includes three post-egg life stages. First, after feeding, an engorged adult female will lay hundreds of eggs at a time. Once the eggs hatch, larvae emerge and wait for a host. Larvae have only six legs instead of the eight legs that characterize nymphs and adults. After feeding and becoming engorged, larvae detach and molt into nymphs. After nymphs similarly successfully find a host and feed fully, they molt into adults, mate, and the cycle repeats. Soft-bodied ticks (Argasids) also have three post-egg life stages, but within the nymphal stage, they might have multiple instars (i.e., molts). Each instar requires a blood meal, after which they molt into the next instar or adult stage.

One-Host Life Cycle

These ticks stay on the same host their entire lives except to lay their eggs. For example, Winter Ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) live on moose throughout their life span, causing a distinct pattern of hair loss called “ghost moose.” Humans are a rare incidental host of one-host ticks and thus are not of high medical importance.

Two-Host Life Cycle

Ticks with two-host cycles generally have a two-year lifespan. After overwintering as larvae, they seek their first host, usually a small mammal, in the spring. The next winter, they remain in the nymph stage, then molt into adults in the spring. Adults feed during the summer and lay eggs in the fall. One of the ticks with this life cycle can vector Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, which is not found in Michigan.

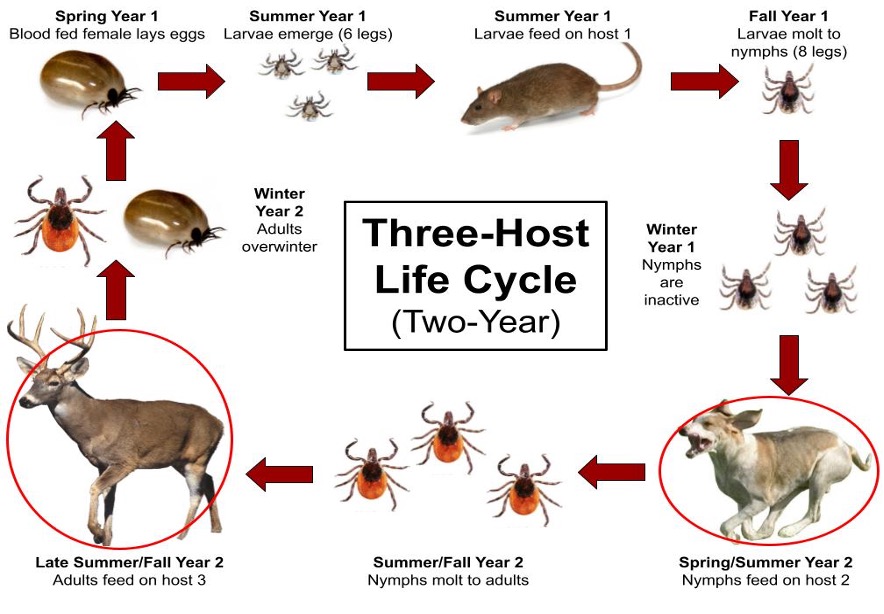

Three-Host Life Cycle

Ticks with a three-host cycle normally have a two to three-year life cycle, depending on local climate conditions. The blacklegged tick, which can vector Lyme disease, follows this life cycle. Larvae seek their first host in summer, molt, and then overwinter as nymphs. Nymphs find their second host in the spring, molt and then may begin host-seeking in the fall as adults. Adults overwinter and then host-seek again during the following spring. If winter temperatures rise above freezing, adults may become active as well. Adults often feed on a larger host, such as deer.

Figure 3. The generalized life cycle of the blacklegged tick, an example of a three-host hard tick. Most ticks of medical importance are three-host ticks. Red circles indicate seasons with higher rates of disease vector activity, with nymphs in May-July causing the greatest numbers of Lyme disease cases Note: Adult ticks actively host-seek from fall through spring of Year Two, pausing when temperatures get too cold (i.e., below freezing).

Tick-Borne Diseases

Lyme disease, caused by blacklegged (deer) ticks (Ixodes scapularis), is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. At one time, blacklegged ticks were rare in Michigan, but their abundance and range have expanded over the past 30 years. Correspondingly, the risk of Lyme disease has also been increasing steadily in Michigan. Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete—a corkscrew-shaped bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi. Signs of Lyme disease can include fever, rash, facial paralysis and arthritis. Erythema migrans (EM) rash occurs in some people 3 to 7 days after being bitten by an infected tick. The classic “bull’s eye” rash is often associated with Lyme disease, but the rash (shape, size and color) can vary widely. If left untreated, Lyme disease can affect joints, the heart and the nervous system. Lyme disease can be treated with antibiotics, but it is important to start treatment as soon as possible. Removing the tick within 36 hours will prevent transmission of the bacterium that causes Lyme disease (Fig. 4).

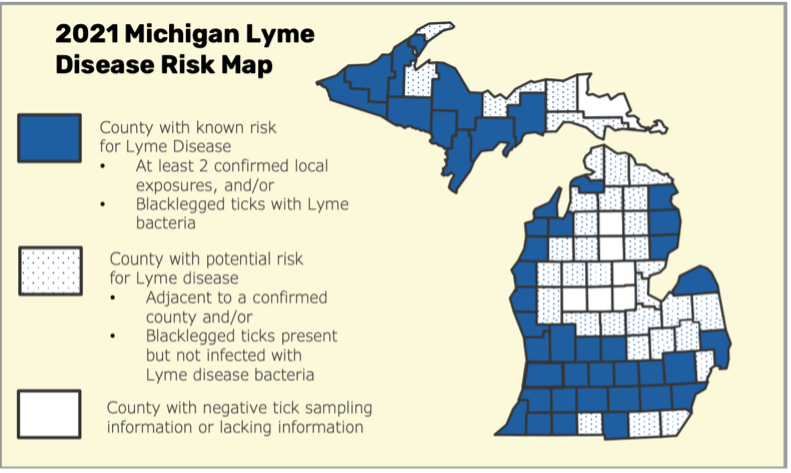

Distribution in Michigan

What to do if a Tick Bites You

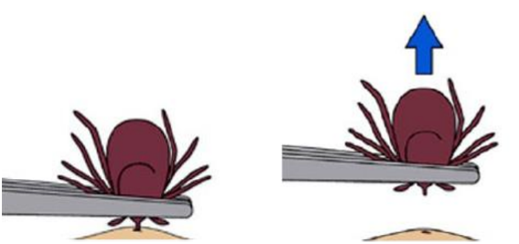

DO NOT PANIC! Tick removal is simple but should be done carefully due to the nature of the tick’s mouthparts.

- Use fine-tipped tweezers to pinch the mouthparts (a.k.a. the “head”) of the tick at the surface of your skin.

- Pull the tick STRAIGHT UP and out. If you are met with tension, DO NOT twist or jerk the tick. This could cause the head/mouthparts of the tick to remain in your skin. If the mouthparts remain in your skin, try to remove them. If this proves unsuccessful, leave them and allow your skin to heal.

- Clean the bite, as well as your hands, with rubbing alcohol, an iodine scrub or soap and water.

- You may develop a small bump or irritated area where the tick bit you. This usually lasts a few days (3-5) and it is not a sign of Lyme disease (see Tick-Borne Diseases section for the difference).

- Keep the tick for identification. Preserve/kill the tick by placing it in alcohol or freezing it. DO NOT smash the tick. It will be much easier for your doctor to identify the tick if it is intact.

- Contact your healthcare provider if you have questions, especially if symptoms of illness develop.

NEVER put hot matches, nail polish or petroleum jelly on the tick to try to make it pull away from your skin.

Prevention

Before entering the forest

- Have materials and supplies ready to remove and store a tick as well as to clean the bite area.

- Stick to the trail

- Be alert, especially during both the nymphal (late spring/summer) and adult (spring and fall) blacklegged tick activity seasons.

- Be alert, especially in areas of the state with known Lyme disease risk. (Michigan Lyme disease risk map).

- Use an EPA-registered insect repellent (e.g., DEET, oil of lemon eucalyptus (or PMD), picaridin)

- Wear permethrin-treated clothing and treat shoes and gear (CDC instructions here)

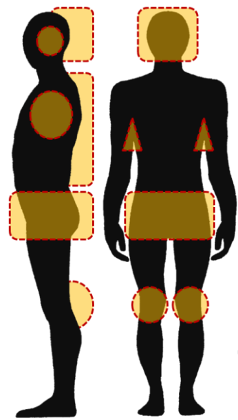

After spending time in a forest

Areas to check: Scalp, ears, underarms, belly button, waist, back, behind knees, pelvic area and inner leg areas.

Ticks search for warm, moist areas of the body, so these areas are most attractive. Feel for bumps and look for small spots all around your body with particular attention to these areas.

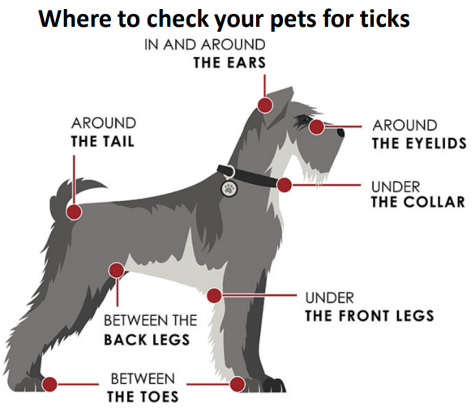

Ticks and your companion animals

Just like humans, animals can be bitten by ticks and be infected with the same tick-borne pathogens that humans can be infected with. The best way to protect your pets is to make sure they are up to date on their tick prevention products. Talk to your veterinarian to decide what prevention measure is the best for your pet. Animals may carry ticks into your home, so after hiking or going outdoors with your pet, make sure you do a thorough check for ticks.

- Run your hands over the animal’s body to feel for any bumps.

- Checks around the animal's ears, chest, underbelly, legs, feet, between the toes and tail.

- A Lyme disease vaccine is available for dogs. Ask your veterinarian if this is an option for your pet.

Removal of ticks on your pets follows the same method as on a person. Any signs of illness normally appear after 7-21 days. Watch your pet for changes in appetite and/or behavior.

For More Information

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Michigan: Ticks and Your Health

Adult Tick Identification and Related Diseases

|

Name and Vector *Click disease name for more info |

Identification of Adults |

Image |

|

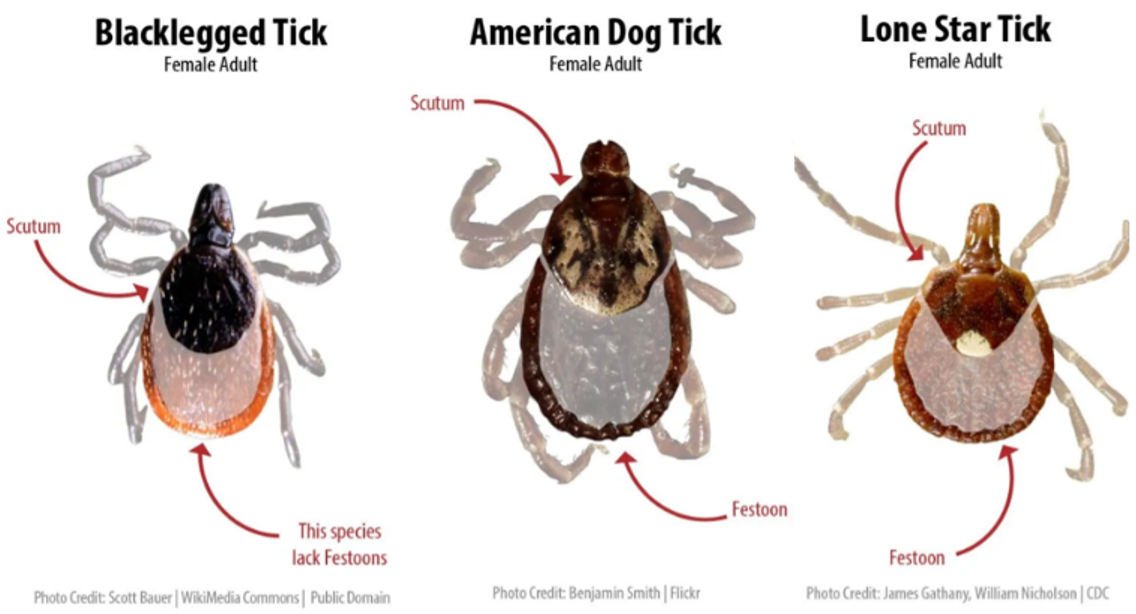

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis) Vectors of: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia (rare in Michigan) Commonly found on pets |

Characteristics: Pale brown or reddish–brown with white pattern over scutum; festoons (light colored markings) present. Habitat: Common in Michigan grassy areas and forests. Most active in spring through mid-summer. Males can be identified by the vertical white markings – “suspenders" while females have a short white “necklace.” |

|

|

Blacklegged Tick; also called Deer Tick (Ixodes scapularis) Vectors of: Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus, and ehrlichiosis Commonly found on humans, along with other animals. |

Characteristics: Red abdomen, black scutum and legs. Festoons absent. Habitat: Less common than dog ticks but range in Michigan is expanding; relatively common in forests. Activity is highest from early spring to late fall, or whenever temperatures are above freezing. See life cycle example above. |

|

|

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum) Vectors of: Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Tularemia (all rare in Michigan) * Associated with red meat allergy Less common than dog ticks and deer ticks, but will feed on humans and pets. |

Characteristics: Reddish brown; females have a distinct white spot on scutum; males have small white markings on the edge of the scutum; festoons present. Habitat: Not common but can be found in wooded or grassy areas; established populations have been found in southwestern Michigan. Active April through late August. |

|

|

Woodchuck Tick (Ixodes cookei) Vectors of: Powassan encephalitis Less common, found on pets. |

Characteristics: Brown with dark brown scutum; festoons absent. Habitat: Found in/near the dens of skunks and woodchucks. Occasionally feed on humans, but hosts are usually animals. |

|

|

Brown Dog Tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) Vectors of: Rocky Mountain spotted fever (rare in Michigan), canine babesiosis, and canine ehrlichiosis Less common, found on pets. |

Characteristics: Reddish-brown; scutum matching the body and lacks white markings; festoons present. Habitat: Closely associated with humans; can be found indoors year-round, often in door or window frames. |

|

|

Asian Longhorned Tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) Vectors of: Theileria orientalis Ikeda (Bovine) Less common, rarely bites humans, will feed on pets and is a tick of livestock concern. |

Characteristics: Reddish-brown body and scutum; festoons present. Habitat: A pest of livestock (mainly cattle); reproduces parthenogenetically (without a male). Active June-August. |

|

Credits

-

Tick Identification Images 1-5 – Cornell University

-

Tick Identification Image 6 – James Occi

-

Figures 5 and 8 – Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Print

Print Email

Email