Compost and Biochar with Brooke Comer

February 19, 2021

Frequently Asked Questions

What sorts of things should I avoid putting in my home compost?

There are a lot of factors that go into this! Here is some general guidance. Consider that home systems generally don’t reach temperatures necessary to safely biodegrade meat and bones to avoid soil borne diseases. Likewise, avoiding excessive amounts of foods that will increase salt or cause a very acidic PH (like rinds from citrus) is advisable. Everything in moderation! Consider this resource as a guideline: https://www.epa.gov/recycle/composting-home

Why does my compost smell and have tons of flies around it?

Have you been saving compost scraps until they form a dense, wet mat? Generally, bad odors are due to overly saturated compost that doesn’t have access to enough oxygen. This can be remedied by turning your pile more, adding fluffy, airy brown materials. If you have some fresh wet material, this can also be the reason for flies. Limit this by turning frequently to allow greater air flow.

What is the best way to apply my compost to my garden?

There is no best way, so consider a few options! If you have small amounts of compost, you can apply it directly to the roots of your plants either in the starting cells, when transplanting, or side dressing. This will ensure efficient use of the nutrients created in your compost. If you have large quantities, tilling it in can organic matter in your garden on a larger scale, making it more available for future years of plant growth. Generally, you want the compost shallow enough that plant roots can reach it to absorb the nutrients.

Resources

- Knowing what’s in your soil can be the first step to a productive gardening year! Get a home soil test kit at insert home soil test kit which can be ordered at https://homesoiltest.msu.edu/ and sent back to MSU labs. It will help you understand more about what you need in your garden to increase soil nutrition and plants ability to uptake nutrients and water! You can check out our Cabin Fever Conversation on Soil with Ali Zahorec from our 2020 season to learn more about the life in your soil and get jazzed about Tardigrades again (although we’ve never stopped being jazzed about tardigrades!)

- A Users Guide to Compost (Oregon Extension): https://www.oregon.gov/deq/FilterDocs/UsersGuideCompost.pdf

- Growing Local Fertility: A Guide to Community Composting (Institute for Local Self Reliance): https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/growing-local-fertility.pdf

- MSU Extension’s Smart Gardening Guide to Composting: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/composting_a_smart_gardening_practice_to_recycle_garden_and_yard_waste

- MSU Extension resource on how to set up a worm bin (vermicomposting system): https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/vermicomposting_a_smart_winter_compost_option

- For further learning on biochar, consider these two bulletins out of Colorado State and Utah State Extensions on Biochar: https://extension.colostate.edu/topic-areas/agriculture/biochar-in-colorado-0-509/ ; https://extension.usu.edu/dirtdiggersdigest/2018/what-is-biochar

- Another great resource for home composting out of Cornell Cooperative Extension: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/29111

Video Transcript

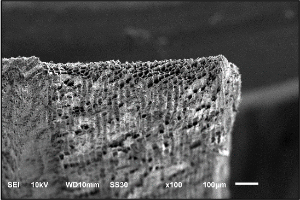

Started. We're really excited to have you for Cabin Fever Conversations today, our third episode in our 2021 series. Today we're really excited to have Brooke Comer as our guest. Brooke is a local Lansinite Lansing-nite, Lans-tronaut whatever we're called in Lansing, Michigan. And recently completed her PhD at MSU and is a composting whiz around these parts. So we're excited to invite her to share her wisdom and joy and delight of all things compost. So welcome Brooke. Thank you for having me. Absolutely. And before we get too far along, we just want to ask you because we're, part of our focus is trying to get folks in a space of maybe thinking outside of the dismal gray winter. So just wanted to ask you what's bringing you joy right now or what do you get really geeked about with compost? What's kind of your reason why for that? Well, you'll see that some more in the presentation. But I just, I love soil life. It is this kind of unknown realm almost that's right below our feet, always has been. And yet there's so much we still don't even know and just how it all works together and how it can help improve it and that we can get out in our garden. And with using composting, just make our soils better every single year and just keep making these improvements and thinking about getting out there again and getting things in the ground. I'm just I'm I am enjoying the winter. It is good, but to get back out there and see greenery and maybe some flowers and things like that will be really nice. But I'm actually, the snow is bringing me joy also, yeah, it gives us the chance to pause. Totally agree and gives us a chance to hibernate and, and take a beat and plan and get excited and get inspired without that kind of fervor that summer brings of having to do do, do, do, do style. Awesome. So we'll just go into what you have to share with us today if that's good. And if you can kind of give us an introduction to your world of compost and how you got there. That sounds great. I am going to go ahead and share my screen here. Hopefully guide me through the PowerPoint there now. Amazing yes. Compost and bio char home practices for healthy soils. was kinda the bigger title. This is not going to be a how-to compost because like 30 minutes and there's so many aspects to it. So it's going to delve a little bit and just try to get everybody excited about it and why you should care why you might want to compost what kind of composting system that you might be interested in doing. And then there's so many resources out there that once you're all excited, go out there and implement it yourself. And that if you're already composting where those resources are, that if maybe you've had issues, then how you can improve on your practice and everything else. So and bio char is something that really geeks me out. It's kind of a newer thing of where you can store a lot of carbon in the soil. And I'm gonna get to that sort of at the end. And that's something that people aren't nearly as familiar with, but how it can work together with compost. And so you see kind of the, well, if it's not covered up on your screen by by all of us. Compost. You see the pictures when it was seed starting and everything of all the beautiful plants and compost. It's different shades of brown, so it's a little less exciting for the photos. You see a bucket there of the grow green vermicompost, which is compost from the systems that I helped develop at MSU. And so you have some nice photos, but ultimately here's a much more beautiful one. Is this is really how I got started is the marine life. I was working in the Peace Corps, tried to do some coral reef preservation and it's like, alright, well, what's really causing all these issues? We need to look on the land. And so again, with compost pictures aren't as pretty, but this is really what people are ultimately going for. So there's your goal. How do we help build up those soils and make a nice, healthy garden and kind of find that balance in life, the life of the soil and the plants that you're trying to grow and, and get it all working together. I know those shades of brown or not that most visibly appealing people to all things. But I think once you know what's going on in there too, and you know what to pay attention to when you're looking at soil. They can be really beautiful too. So I completely agree on one thing. And we had talked about this before, that it's a lot more fun really for me, especially to do these types of workshops in person because I have a bunch of different kinds of compost and I have worms and everything else and you can actually feel it and get your hands in it. It's a whole different thing. It doesn't display as well on the flat screen, but just that beautiful, rich, dark compost that you see. It really is a beautiful thing. And then life, all of life and so much of that you can't see that's the thing if you get the microscope out than it really is pretty darn exciting. And there's so much happening in there you just can't necessarily see it all. My as, as Abby mentioned, I got my PhD recently from MSU. So I'm here for a number of years. And kind of why I have at least a little bit of expertise here as some of the composting work that I have done at MSU where we were composting a lot of the food waste coming off of the dining halls, both hot composting and vermicomposting or worm composting. And the bigger the picture of the hoop house there with the snow is pretty fitting for right now. And that thought that even then our cold climates, you still can do a lot of these things with vermicomposting. This is obviously on a much larger scale than any of you are probably going to do. But you can keep them warm enough through the winter, even if they might be moving around through some frost, if you're using worms. Of course. For me I would just bring my worms inside because on a home composting scale, you're probably just going to have a bin or something like that. But so you see the kind of quantity I used to be dealing with all the time of these big bins getting wheeled off of a truck and dumped and then mixed and creating both the hot compost and taking that and feeding it to worms. And so I've been creating a lot of devices just to hang around in my own backyard. Before coming to Michigan, I had also been working internationally and helping set up composting systems in a number of different communities where so much of it depends on what you have available and and what exactly you are going for. Sure. Can I ask a question Brook, just just generally about compost? So what are some common soil issues that people should be on the lookout for and know compost is appropriate, an appropriate amendment? I mean compost really is almost always an appropriate amendment. There's, you could possibly overdo it, but it would take a lot of compost, then you might need to be careful of what compost you're using, that it doesn't have a weed seeds or something else in it, but you could put quite a few inches all over your garden mix it in with the soil and it's going to be a really big positive. So it's compost is as nearly it's mostly soil organic matter or organic matter that you can incorporate into that soil. And creates this nice mix that really helps with the nutrient cycling and helps make all of those nutrients that are in the compost or already in your soil available to your plants. And so there's really never a bad time to add compost even if your soil is already pretty healthy. But if you get a soil test, which I would really recommend to any home gardener, that will give you a lot of different information, mostly about your macronutrients like your nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium. And also if you have any issues like heavy metals, especially in an urban setting, that could be very important to look at and, and compost can also help some with the remediation of soils that might have issues. And it'll tell you what your pH is also. And that's super important for gardens because plants thrive at certain pHs. And, and also depending on what you want to plant, getting some information about those plants and the type of environment they are going to like the most. Oftentimes at least it seems like in the Lansing area, a lot of the soils are actually pretty alkaline or above that neutral pH. And so you might need to be a little careful to not increase pH depending on what that compost pH is. But in general, almost, almost always adding some compost it's not going to hurt anything and it's going to show some benefits. Good to know. So this idea again, kind of what we're geeks me out is the circular economy. I just, I love this term of how can you reduce your inputs that you're putting into your, into your farm or garden and reduce the outputs. So composting, One of the biggest things to me is that I am not sending any organic matter in the garbage to go into a landfill. And, and so now not only are we able to create compost and then healthier soils for our own gardens. But we're helping the greater world and creating less pollution. And things like that where this organic matter is really wonderful and lovely and has nutrients and all of these things. But if it's not utilized correctly, then it can actually be a negative. And so even within just that smaller scale of a home garden, trying to reduce what you have to go out and purchase necessarily, and what you can actually produce for yourself. And part of why it's so exciting with compost is, and I've mentioned all that life that's in there is, there are so, so many organisms, it's particularly the bacteria and the fungi. And then this little slide here talking about the plants all the roots and other things that are happening and you get things like your nematodes and your worms, the amount of life is really incredible. And if you just keep tiling your soil year after year, like over tiling and not adding any organic matter, you're really going to be reducing that, that soil life quite a bit. There still will be some, but to really create a dynamic system where there is so much more kind of functional diversity within the organisms that, that they can help make it really a healthy environment. And one that you're not going to see as much pest and disease and insect pressure and things like that. If everything is kind of in harmony and you're working with nature in that way. So a big part that you always want to consider is are you going to do hot or thermophilic composting? Thermophilic, meaning hot loving or vermicomposting, which is more at those ambient temperatures, as is not the only means of composting. Some people, maybe I've heard of sheet or lasagna composting also where you layer a bunch of materials and they're not in such a way that they really heat up, but they do eventually break down. But most people, when you talk about composting, you're either talking about hot composting or worm composting. Now I really like worms. That's kind of a little bit sexier. You get into, you know, something that you can see moving and, and everything out. But depends on a lot of things. So, you know, what resources do you have? And that's just, not just resources, but things that could otherwise be going into a waste stream. So think about what you have on hand. How much food are you producing in your kitchen that tends to not get eaten. And so there's obviously so much food that you're not going to necessarily be eating. I scrub my carrots and potatoes, I don't peel them, but some people do. And there's the portion you would be discarding from food like pineapple tops and skins and melon skins, those types of things. So how much are you typically producing and, and what resources might you have? For example, my husband and I, we always collect fall leaves. We actually leave our leaves on the grass so it can kind of create a nice environment. That's really recommended, but so many people go out and rake all their leaves and they put them in a nice bag. Just perfect for you to go pick up. So we'll go around, will pick up a bunch of these leaf bags and then that becomes our carbon. But, but just what can you utilize, especially that's free, that might otherwise not necessarily get wasted. A lot of that actually does get composted and municipalities, but but what you can do for your composting system. It also depends on sort of what scale, right? Space. That really depends on what kind of scale you're going to be and the resources, yeah, how, how much you are producing. If you just have a little bit of space, maybe a worm composting bin is more what you would be interested in and they need some bedding. Oftentimes with composting, you talk about browns and greens. To kind of, if you've gone to any kind of composting workshop. You've maybe heard that browns have more carbon in them. Green material has more nitrogen. And you really want to get this nice ratio. There's a lot of wiggle room in there. You can be very specific with the compost calculator of just how much you want of one material versus another. But if you roughly get normally it's like a three to one of brown's to greens. You're probably where you want to be. But for vermicomposting, the browns are kinda like the bedding. You want to give them something nice to live in, like news paper or cardboard or peat moss. And then once they kind of have that nice environment, you're just adding the food in and that's what they're eating. So if you have a limited amount of space and you just want to be utilizing your kitchen scraps, then that might be more appropriate. If you have a big family and a really big garden and space in a backyard, then you might want to do the hot composting routes. And there's so many different types of systems that you can utilize or maybe have hot composting and worm composting. You know, so so many possibilities or maybe you have a community garden where people are composting collectively, which is really great. One of the things I love that you said Brook was reframing some of that food waste and leaves and those things that are nationally around as resources, I think so often we think of them as like problems that we have to manage or dispose of or find a place for vs. viewing them as actually, you know, that organic matter that's trapped up and resources that you can really leverage for garden inputs and for making that incredible soil. So it's just a, it's just a shift in framing that I think can help change the way you interact with your compost? Absolutely. And that's such a huge part to me, is yes, change that paradigm of the way people think about things, don't think stuff is waste. And about how we can become in that circular economy, how it can be an input itself instead. So and then besides the space, how much time or effort you want to put into this. And I say composting can be as easy or as difficult as you want it to be. You know, if you want to get out that compost calculator to weight it out all your material and everything else. Sure. If you want to turn it a whole bunch of times, that's great. You're going to get compost a little bit faster. And you might get compost that has a little bit better quality. But it's to be a lot more effort that you're going to be putting into it. And if you do that, then it might go, like said, go quicker. Or if you're just a little bit, I want to compost. I don't want to throw this in the garbage, but I don't want to spend a lot of time, pile it all up. It will break down, especially if you get those ratios of Brown's to greens, right? And then why are you composting? Is it just that you don't want to throw stuff into a landfill or is it that you really want the compost or maybe you just think worms are really cool. And it's a really good educational way too. I love looking at our worm bin with my daughters and they get all excited about it. And you can see that break down happening a lot more in real time. So there's a lot of different reasons to compost. And it just depends on what kind of system you're going to go for with what you want. A very common type of backyard composter is a bin system. I especially like one where you can sorry, pop up on my screen. I especially like one where you can start everything in one side and then flip it over into a next side after you kind of have enough material. I find on this home composting scale. Again, this is not exactly a how-to, but a common troubleshooting thing is it doesn't get hot, is if you are putting all your kitchen scraps and try to get those browns and greens so that way you don't have smell. So as you put in a bucket of your kitchen scraps, put in a nice big layer of dry leaves or shredded paper or shredded cardboard along with it. So you're kind of creating those layers that are going to be interacting, promoting those microorganisms. But it still might not get very hot. But if you keep building it up that way, and then once a month or something, you go out in your garden and you weed. And of course you try not to let them get big, but you have, once you really weed you have a really good amount of material. That might be the time to re pile everything. So maybe flipping it from the one side where you were collecting into the other side and get get it all mixed with that fresh green material, some more of your carbon material, and then all that food waste that's been sitting around for a while, you build a pile that has a lot of volume all at once, you're more likely to get it nice and hot. And I would also recommend if you're really into this is getting a compost thermometer for one thing, the educational side and getting excited about it, it's pretty cool to see just how hot it can get. You can also stick your hand and if you can't hold it there for more than 5-10 seconds, you're probably at that temperature you want to be. And that temperature aspect is more so for killing weed seeds and killing potential pathogens where you don't want to be spreading those in your garden. And again, you should look online for other resources and resources will be sent out to everyone with some Extension bulletins and things on the different types of composting. But if you have diseased plant material, better just to get rid of that altogether. Even though your home compost gets hot enough, if it were to not get hot enough to kill the disease and then you spread it out. You have early blight and then you spread that on your tomato plants in the compost, then you're gonna be spreading the disease back to your own plants. So you want to be careful of things and same thing if you are weeding and your weeds have already gone to seed, you still might take the plant, but take those seed heads off just in case you don't get hot enough to actually kill the weed seeds. But it's a matter of how much effort you want to put into things. So Brooke, We have a couple questions that might go into this a little bit. So there's a question about you mentioned green and brown materials. And I think a lot of folks know the greens that they produce in their house and things like that. Can you share what might be some common materials folks would use for those browns? Like I said, collecting the dry leaves in the fall. And if you have enough space to get a bunch of those bags, if you also have a means of chipping the leaves, then you can take like ten garden bags and probably make it into just two If you just reduce, if you just chop them all up. And in general also with composting, especially for worms if you chop stuff up and make it smaller. It'll go a little bit faster. It just mixes in a little bit better, but it's more a matter of how much space you have, but collecting those leaves can be good. Newspaper, other office paper can be fine. Cardboard is really great. You know, all of those types of things are going to be very effective. Straw also, hay is more of a green. And even if it's kind of dry, it has a lot of nitrogen but straw, which is a lot more yellow, it's more the hollow stems and you can get a bale of that that makes a really effective brown or carbon heavy material also. And then a couple other just simple systems. This type of bin that you build up, the one on the left, the black bin. It's nice and contained so you don't worry about critters getting into it. And you can actually take little drawer off the front and pull out. In theory, what could be finished compost from the bottom as you keep adding on to the top. Or it's just a place where you collect all your materials until you can make that bigger compost pile that really heats up or a compost tumbler. My experience, a compost tumbler, I haven't had any luck with them heating up. So I'd be a little more cautious. But in general, with any of these things, see what works for you and your system. Things that you have to buy though, you want to feel more confident that that's what you're going to want. And then vermicomposting. I was just gonna say what looking at those 2, we had a couple of questions from folks about critters getting into their compost. Some bears, I'm not sure where that one's coming from, but bears and snakes and things like that. So systems like this would probably provide that necessary barrier from most critters being able to get in one would hope, Especially the tumbler. I mean, if you get a tumbler like this, I mean, most even mice wouldn't be able to climb up those kind of slippery parts of the tumbler. But also making sure that you are putting enough that carbon material in. Your compost really shouldn't smell. And if it smells, that's what's probably going to be attracting, attracting the critters. And although you, you can get away with putting some cooked food in especially if you really have a hot pile. But in general, they, the, the recommendation is to avoid cooked foods, especially because they probably have more fats and salts in them and you don't want to increase the salt content of the sodium and chloride. Table salt kind of contents of your compost. And avoiding those cooked foods will help a lot for avoiding the critters, too. And then worm composting bins all sorts. This most common kind is you take a plastic tote, put some holes in it, and that's the type of bin that you have. Here are some that I worked with at MSU. Those two wooden crates are wheely carts with worms in them. And then you can just kinda tuck them underneath of a table and you still have your nice work surface that was really great. Here was using bulk bags, the kind that they have on farms, created a little structure. So use what resources that you might have available to you. Don't normally have to actually spend that much money into creating a system. And this was, again for bigger worm beds or this kind of bigger tote system. This is what we call the flow through where we put material in and those bars, the finished compost would fall out the bottom. Larger scale vermicomposting systems normally use a version of a flow-through system like this or big bed systems. So create a big batch and then you can even grow stuff on top of it. Might not be the most convenient, but you see here with these bed systems and then plants are growing over top, there were elevated up. So now think about your space and how you can maximize your space. This is in a hoop house where those aren't cheap. And so, especially if you have something like that, trying to maximize what you can do in that area. This is again with the worms and keeping them nice and toasty. Even in Michigan even in winter. Just back to vermicomposting, There was a question about how many worms you need I have a feeling it depends on your system. It kind of depends on your system, but there is a general rule of approximately one pound of worms per square foot. So you normally talk in square feet because they mostly stay just on the surface area on the surface layers and they don't go very deep. So you don't normally end up with very deep vermicomposting systems. And so that is the goal you might go for now if you have a slightly bigger been starting out with just a pound of worms, even if you have two or three square feet of surface area, would probably be enough. And then they'll multiply. If you create the right conditions, you're going to start seeing these little worm cocoons and you'll have more babies and start getting a lot more of the different size classes. But that's the general standard is approximately one pound of worms per square foot, which is about 1000 worms in a pound of worms. I normally have this photo of. A pound of worms is about this big if they were all squished together. Yeah. And you normally if you're purchasing them online, which is the way a lot of people might get started. You normally purchase them by the pound and they can get shipped to you. Also, if you know somebody that has a farm, a lot of them. So you want certain kinds of worms normally called the red wigglers. That's a very common one. There's other composting worms, but they are around in the natural environment, especially if somebody has maybe a horse farm or something like that. If you go out and there's some horse manure, especially if any of it's piled up if you look through that. It may gross some people out, but especially if it's broken down a little bit, you're probably going to find these type of red wigglers or worms and you can just go and collect them from the environment, put them in your worm bin. Now you don't want just general earthworms, the bigger kind that you see in your garden and those burrow down deep and they like mineral soil and they're not going to be processing so much organic matter so quickly like you want in a worm composting system. But you can, you can still find some of them in the natural environment, too. But that's a good goal, is one pound per square foot. Yeah, I always think of those earthworms is a good indicator that your soil has those pockets and that it's kind of rich and other ways. But I, when I first thought about worm composting, I tried to do it with earthworms. This was many years ago, and I learned my lesson. I didn't do it, didn't help as much as I thought it would, so yeah, exactly. They are probably going to just try to flee your system. And, and even with the right kinds of worms, you might want to be careful. But first, one thing I recommend is that use light to your advantage. Worms don't like light. And so if you're just establishing a worm bin or a worm system, then leave lights on all the time even through the night. If you're able to, because then they're more likely to stay in that material and not try to escape. Because if you don't create a nice environment for them than they might try to try to leave. And this was before I started at MSU, but we had this container of dried up shriveled worms of saying like this is why we need to be careful. Because then they'll all try to leave, then they dry out and they die. I was going to say Isabel has a great worm story. Oh, just everybody know, it's okay to fail. It is okay to fail. It's a all about learning. But our system, they didn't have enough air getting to them or enough oxygen so I think they ended up suffocating. And I like that advice Brooke to use light to your advantage because it is interesting how they kind of stay in that surface area. And yeah, just it was not an ideal environment for them and a failure. But it's okay. Yeah, don't let failure stop you and certainly, you know if it's that they suffocated worms breathe through their skin. They need it very moist. You want like a wet sponge that if you squeezed material you get a couple drifts coming out of your hands. But if it's overly moist and like sopping wet in the bottom of a worm bin, then then it's gonna get putrid and smelly. And it's not going to allow the oxygen to kind of infuse into that for them to be able to breathe. And just creating airflow and finding that right balance of how much moisture is important. So and then with all of this, you know, why and how to use your compost. Talked about a lot of the why's of reducing your input cost of other fertilizers and things like that. Maybe while you're also improving your soil and you're just building up that soil organic matter year after year. There's kind of a limit to how much you can build it up because it cycles, it continues to break down, even if it is in that pretty stable form of humus. But you still can increase it to a degree, especially if you have sandy soils and things like that, it's hard to bump up your soil organic matter, but the more you can, the better and compost is really your best strategy. And how to use it. It kinda depends if you have a lot of hot compost, if you were making a lot yourself or if you buy it by the yard, which even in a backyard setting might be a really good choice for some people, then that type of more municipal compost, it's not going to be quite as high in nutrients. It's still gonna be great stuff. Has a lot of stable carbon that soil organic matter that you're adding. And you might just spread that out over the whole garden or your beds. Rake it in, incorporate it just a little bit. But if you're buying it by the yard, then that's not that big of a deal. Now if you are making it yourself or if it's the worm compost and you're like, alright, in a month I made, you know, a gallon or two gallons of compost. That's not going to go very far. If I just sprinkle it, then maybe thinking about just putting it right around the plants that you planted so you're really just feeding the roots of that plant in particular can be a good strategy. Also. Here's some from my, some of my research of using compost both as a top dressing. Those are the top photos you see on the left. For both of these is where no compost was used at all and then increasing amounts. And so all of these were started at the same time. These are cucumber, seedlings. You see the very obvious effect. A photo I don't have in here is where we incorporated vermicompost into the starting plant media, the root media. And they didn't do as great at like two cups per flat rate versus the top dressing because really sprinkling on top and then those nutrients percolate down through as you water and everything can be a good way. And the compost extract is also sometimes called a compost tea. And people are, a lot of people are very interested in this also. And again, all of these topics I could talk on for an entire day each. But it's basically where you mix compost in water and you're trying to extract those nutrients and more importantly, extract those microbes that are in the compost and be able to spread them out over your plants. And sometimes it can be a little easier to spread them out. You know, if you have one gallon of worm compost and you have a backyard that is 300 square feet for your garden. Then sprinkling that around each plant is more difficult, but maybe if you did an extract, then you could spray it over all of the plants or at the root zone and, and get the better use of it that way. There's a lot of different kinds of compost tea systems and ways that you can do it. And again, that's a whole other topic, but just one way that you can utilize your compost if you wish. And lastly, going into bio char, of this being something in particular that I'm really excited about. Some of my research did focus on this and incorporating bio char into composting systems. So basically bio char is charcoal, but it's charcoal with a specific purpose of adding it into the soil and adding it into these systems. And charcoal is just, it's really any organic biomass. You can make it out of all sorts of stuff. So you can make it out of wood. Big logs or wood chips I've seen it made out of rice hulls. You can make it out of things that again, might be in a waste stream sometimes, but instead you make it into a resource. Bio char sometimes could be made out of poultry litter and things like that. And the main aspect is that you are heating it at high temperatures under low to 0 oxygen. And you create this form of carbon that is really resistant to break down, call it recalcitrant and it has this beautiful system. You see that kind of honeycomb structure. This is a very zoomed in version on bio char. And one thing I like to say, it's like a little hotel for the microbes. And it has all these binding sites for increasing your nutrient holding capacity in your soil and also increasing water holding capacity in your soil. So this is something that gets me super excited. And where this is coming. It's a little bit newer. In terms of the scientific fields. For a number of decades people have used it. But you know, versus compost and being done for a long time. But biochar and how you can utilize it in a composting system as pretty exciting. And here talking about some of the things that it can help do for your soil. Just a nice little graphic of how it can help. And with this too, if you are adding biochar in your compost, biochar, especially if you purchase it or something, then you might want to concentrate it more around the root zone instead of just broadcasting it everywhere. And I was originally introduced to this actually in Southeast Asia. And so biochar again, you can purchase it and then you know a little bit more. With bio char it really depends on so many factors. What that bio char is going to be like it depends on what it was made out of. It depends on how hot the temperatures were, how long it was heated for, and what that oxygen content was. And it makes very big effects on the final bio char. So it's just one term, kinda like compost. People say compost. But it can be all sorts of things. It can be super high in nutrients, or it can be really pretty low in nutrients or lot of organic matter, but it just depends. And the same thing with bio char. There's a big continuum of the types of properties. And then with that and with compost, you add into the fact that you are mixing it into soil and there's so many soil types and everything else that I'll just kind of depends on, on your system and how things are going to go. So with any of this, I say, test things out on a smaller scale if you're nervous about how somethings are going to react. With biochar, you can actually make it more of a backyard setting. So this was a really cool little biochar reactor. And even collecting the condensate, which is sometimes called wood vinegar, that can be used as a pesticide. So this would have been waste wood and waste bamboo. This was in Thailand's and instead it's being turned into a resource. Another type of bio char small kiln type of reactor. We're also doing it in larger piles. This was with rice hulls primarily. And where I was initially introduced, they were also using it for animal husbandry systems and they were mixing it in as a bedding of, for a piggery. And there was zero smell. These pigs were normally in a deep bedding system. And so. They weren't really being let out. So all about the feces and urine and everything. And but the way that would combine with the biochar, which is so carb- and I, pretty much just pure carbon mixing with those nutrients. The lack of smell was pretty amazing. And then some of my research where I used biochar and what's called anaerobic digester effluent coming from a dairy farm. Super smelly stuff when it's raw. But you mix it with the biochar and that smell just dissipated, which was pretty amazing. So that's another thing that people have an issue with smell happening or something. Then maybe biochar, another very carbon heavy material, it's black, but it would be considered a brown. Could, could be something to incorporate into your system. And another DIY Bio char, This was here at MSU where we just built a pit out a cinder blocks. You light it on fire, cover up. So you're trying to reduce the oxygen. Covered it all with soil and that's what you end up with. But basically it is charcoal and you can find some bio char. You got the kind of big box stores or look online and things like that, you know, certainly sold more by the five gallon. (Accidental break) about outputs becoming inputs and striving for zero waste. And that gets me really excited and how all these things can work together, both at the home scale and at the larger scale. So the few things that I won't actually go into, but from some different publications, see all the arrows in the flow of everything and how, you know, it circles back around and everything else of creating these systems that really work in harmony as much as you can. And this is where you can have the raw with the bio char and because that with an anaerobic digester where it is helping with the nutrient retention. And, and all of these things. Again, the exact aspects, aspects of this aren't as important, but just kind of the idea of the flow and inputs and outputs creating something that's going to make a really resilient system that you're going to have a great product, and it's gonna help your soils. Amazing . Thanks Brooke. I might ask you to take down your slides so we can answer some questions from the group. Awesome. So we have so many questions. A lot of folks are really into composting and that's great. I think one of the big categories that we've seen is a lot of like, "Can I add this?" questions And so I'm wondering if you can just cover a couple of things that you might want to consider not adding or using caution around adding to composting systems. Just to kind of like bucket all of those questions into one. So if it is organic matter, it will eventually break down into more stable organic matter which is put compost is. But one thing I already mentioned is especially being at least very cautious if not avoiding altogether cooked food. Meat, meat especially could get really putrid smelling and that particularly would attract animals. I mean, it is very possible to compost. Whole animal carcasses even. But that is not what you're going to be wanting to do in your backyard setting probably. And that's where you really need a hot hot compost pile and everything. Cooked foods like said, some of it using it and adding it in moderation can be okay. I mean, hopefully when you cook food, you eat at all, you know that should be the goal. You don't want to send food waste to the landfill, but hopefully, the other goal is eating what you cook and eating whatever goes into your refrigerator instead of at all going bad. I mean, I am guilty as well. It does happen. There's always that one Tupperware at the far back the back of the fridge. You're like, "When did I make that?" I think as long as there's not too much salt and fat and everything, you might be able to add a little bit, but I would avoid those things and then anything that is not straight from nature, so any kind of glass, plastic, metal, all of that definitely avoid. One thing that I've found really annoying at MSU was all the stickers off of like avocado or all sort of the, the rubber bands like alright, chop off the bottom with the rubber band. Then you have all these rubber bands in it which don't decompose quite so quickly. Yeah, do not decompose as quickly. So I'll try to really make sure that you're putting everything clean into your system is always a good idea. Yeah. There's some questions about, you know, grains and breads and some cooked foods. But I think what you said about like, if you can understand the components of the food as pretty basic, right? Bread as mostly flour and water, mostly. Or like if you've got leftover rice, it's mostly just rice and water, kind of as long as you're not adding to the salinity of that, you're probably okay, right? You're probably okay. And also in moderation and in general, like if you just have a lot of variety of things going in, you're probably going to be good. People worry a lot about citrus peels also. But, and I would say, if you eat three oranges a day, I would worry about putting that much again. But if you're like a couple oranges a week, like I wouldn't worry. And so much of composting, especially when it comes to worm composting because those are, they're animals, is pay attention. Pay attention to how they are reacting to certain food sources and things like that. Within a hot composting system. That's a little bit more difficult to really see exactly what's happening, although you can see if things aren't really breaking down. I mentioned stickers on the avocado shells. Well avocado shells, they don't break down very well. And avocado pits don't break down very well. I still throw them into mine. I know that they're not really like I'm going to find avocado pits. I will say though, when I was doing worm composting, when I was more into worm composting, I'd always whenever the avocado pit would come in half, it would be like this massive cluster of worms in the inside there. So there was something they liked about it, even if it wasn't breaking down super fast. And I think thinking about just moderation like you would with your garden, like you do with your diet. Recognizing that worms like moderation too I guess, yeah, Moderation is key. Organisms like moderation. There were so many pineapple tops coming from MSU dining halls. And they wouldn't break down as quickly because those leaves are sturdy. But the worms would be in all of the little crevices of the pineapple tops where where they all joined and they just love them. It was like that's the worm hotel and they'd go out and feed. And also eventually those would break down also. And I mentioned that you can put a lot more effort in if you want to. Some people will grind up, especially if they're worm composting. They will use a blender and they will grind up all their food waste. And I really hope they have a blender that's dedicated just to the worms. But you never know. And that's so that way they can kind of process it a lot faster. And it's a matter of what you wanna do. There's, again, so many resources out there. For one thing, there's a red worm composting Facebook group and people get super nerdy over their worm composting and posting questions or sharing your joy in worm composting can be fun on that. What people, the lengths people will sometimes go to, is as fun and interesting. Treating them like pets. So there was another question that came in Brooke about, so if you do have those red wigglers do you kind of want to just keep them in that system? You don't want to release them out into the world? People are concerned about the invasiveness of them. And how they work in and, you know, a natural system. Oh absolutely, I would definitely want to keep them for, for one thing, there's a good chance that maybe you bought them. So you want to maintain them and build your worm population if you can in your bin, it will come to an equilibrium on its own. But if you want to keep worm composting, you want to keep your worms. Now, if some of them do get into the garden for one thing, they are probably not going to survive very well because garden soil is mostly mineral soil, you are trying to increase that soil organic matter. But these types of worms need that higher nitrogen content, wetter material. They are not earthworms that burrow down deep and everything else. So the likelihood is that you're not even necessarily going to be very successful trying to have them in your garden in the first place. There's definitely concern over the invasiveness. Worms are not native to North America, but they are here. Like I said, you could go out to a horse field, pick up some horse, horse manure, and you're probably going to find a red worms. So that does mean that they do exist around. But I would say try to not let them out into your garden and try to just keep them in your system as much as you can. Amazing. So I think we have one more question about biochar and then we might try and wrap up. And I know you said this is kind of an emerging field of research and something that's really new and exciting. But folks are wondering about the difference between what you're talking about biochar and what you might find in your fireplace after you've used or wood stove or kinda like charcoal and fire ashes like what is how do those things distinguish? So I said biochar basically is just charcoal but more of that lumped charcoal. I don't want to mix up my terminology. You know, you can get the the charcoal briquettes or whatever for your grill, where they're all kind of perfectly the same size. That is not the same thing, but you can also get lump charcoal where you're like, oh, that was a piece of wood. before. And that really is the same thing. Biochar normally the differentiation is that it was produced kind of with a purpose of being added into the soil. But if you are burning in a woodstove, mostly what you're going to have left over is ash. And so part of the concept with biochar is you, you end up with all of the carbon leftover and you burn everything else off. When your heating and you have an actual fire, then you're burning all that carbon off and you don't end up with very much. And ash, has some nutrients and it can be added and it tends to be pretty alkaline. You want to be a little bit careful that kind of material can be added into a compost pile also. But with moderation, I would say careful not to overdo it. But it is not going to be quite the same thing as biochar. Awesome. Feel like moderation is our takeaway for today. Just don't get too crazy with it. Moderation and diversity and the kinds of things you put in. And the biochar is part of a really exciting aspect, I didn't go down at all, is this carbon sequestration. Compost is really stable and you're able to put it in. And so you're storing a lot of carbon in your soil. But biochar is way more stable, way more recalcitrant like we're talking hundreds of years, if not thousands of years. And the thought that you can really store that carbon in your soil environments. And that's a big emerging thing even with like carbon trading markets and things with how can we help global warming put more carbon into the soil where it's going to help everything and it will kind of reduce that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere also. We have oh, go ahead. I was going to say, that's a, that's a great segway into sort of our last question about how can you share this practice with your community or how can it impact your community? Yeah. I loved teaching about compost. So that the way I share as I, I've done a number of different workshops through different organizations. And then with the research that I've done, finally, got my dissertation published, but now looking to publish some of my other research and just troubleshooting with other people. There are those Facebook groups where you can share your joy and everything else. But in community gardens settings too, it's really wonderful. And I was saying how if you're kind of compiling some compost material slowly, but you really want to make one big compost pile all at once to get it to really heat up. Well, if it's an a community garden it's like "Alright everybody, this is the weekend. Everybody come and meet together and then we're going to really mix the compost pile." Make a really big one and kind of get excited about it together. Find, find that joy together over over composting and, and sharing with people what you do know and what you're excited about. And I mean, these little individual actions. It, Yeah, we're just one household or something. And but collectively, it really is amazing what we can all do when we work together. And if everybody had their backyard garden and tried to increase their soil organic matter and didn't throw their compostables into a landfill. It can have a collectively really big impact. I love that well, that feels like a really great note to end on just recognizing that many small actions can create that kind of collective change. So I think we'll close for the day here. Thank you so much Brooke for being willing to come on and share your wisdom and knowledge. Enjoy with us. And I'm excited to dig through the snow in my backyard maybe a little later and find that buried compost pile. Might be a little bit before we can do that, but we'll send out the resource e-mail as always, with lots of resources, both Extension and otherwise, to help you think about what kind of system you want to incorporate into your garden the summer, maybe make some plans. As always, thank you for joining us and thank you, Brooke. Thank you so much. Thank you. And thank you Rachel! our interpreter. Have a great week. We'll see you next week at 12:30. I'm really excited. We're hosting Shiloh Naples from the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance, who's going to talk about seed saving. And it should be really awesome. So join us next week at 12:30 and have a great weekend. Bye everybody.Bye

Print

Print Email

Email