Policy

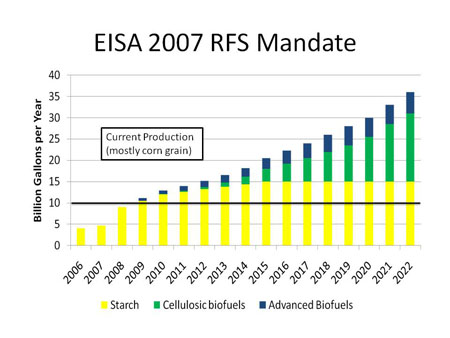

The Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) of 2007 was a milestone in U.S. energy policy. It solidified previous movements toward renewable energy by expanding the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) to 25% of the United States current petroleum consumption (36 billion gallons of ethanol) by the year 2022 (see Figure 1). The RFS was expanded to include 15 billion gallons of ethanol from starch and sugar based feedstocks (corn, sugarcane) and 21 billion gallons from cellulosic feedstocks (corn stover, switchgrass, woody plants). By the end of 2009, we will be closing in on 10 billion gallons. The biggest challenge ahead lies in new technology and discovery of new processes that will make the conversion of biomass to ethanol more efficient and productive.

Figure 1. Renewable Fuel Standard production goals set in the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act.

Biomass is all parts of any type of plant, including the leaves and stems, not just the starch and sugars. All plant cells contain cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin in the cell walls. Cellulose and hemicellulose are made up of linear and branched chains of sugars. Plant cell walls can be broken down, the cellulose and hemicellulose exposed and then converted into basic sugars. The sugars can then be fermented into ethanol and other biobased products, similar to corn ethanol. Conversion rates for different processes and feedstocks vary tremendously. It is estimated that it will take a billion tons of biomass per year to produce 21 billion gallons of ethanol. While this goal seems lofty, it is quite realistic, although it will require a diverse portfolio of products.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) commissioned a study to evaluate the potential volume of feedstock needed in order to meet the objectives of the RFS set forth in the EISA. The study evaluated a variety of issues surrounding biomass feedstock including long term soil carbon and productivity, soil erosion, accessibility, transportation costs, nutrient runoff and feasibility of collection/transportation. Figure 2 shows the relative distribution of feedstock by resource. Notice that the total resource potential is well above the goal at almost 1.4 billion tons.

Figure 2. Annual biomass resource potential from agricultural and forest resources.

More than 25 percent of this potential would come from extensively managed forestlands and about 75 percent from intensively managed croplands. The major primary resources would be logging residues and fuel treatments from forestland, and crop residues and perennial crops from agricultural land.

Production of existing and new biomass feedstocks as well as improving yield will be an important part of achieving the RFS goals. Equally as important is collection of waste and byproducts from processing of forest and agricultural products.

The U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Department of Agriculture are both strongly committed to expanding the role of biomass as an energy source. In particular, they support biomass fuels and products as a way to reduce the need for oil and gas imports; support the growth of agriculture, forestry, and rural economies; and to foster major new domestic industries in the form of biorefineries that manufacture a variety of fuels, chemicals and other products.

Print

Print Email

Email