Emerging Pests

Asian chestnut gall wasp

Download the MSUE Bulletin E3457, Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp for more information.

Asian chestnut gall wasp (ACGW) (Dryokosmus kuriphilus Yasumatsu) was discovered in Michigan in 2015. This tiny insect, a native of China, is a major invasive pest of chestnut trees in Japan, Korea, much of Europe and the U.S. At high densities, the spherical galls caused by ACGW can reduce tree growth and nut production. This invader will continue to spread and could become a serious problem for commercial chestnut producers across the state.

Chestnut growers should be aware of the quarantine in effect in Michigan and Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and any other state where gall wasp may become established. Regulated materials include living plants and scionwood of all Castanea species including hybrids.

History and Distribution

Asian chestnut gall wasp was accidentally introduced into the U.S. in 1974 when infested chestnut plant material imported from Japan was planted in Georgia. Since then, ACGW has spread to at least 14 states, including much of the native range of American chestnut (Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.). Ongoing spread within the U.S. is due in part to natural dispersal of adult wasps, who can fly and who are probably also carried by wind. Movement of ACGW across large distances occurs when people transport infested plant material into previously uninfested areas. Nursery trees, scion wood and chestnut cuttings can all harbor tiny ACGW eggs or larvae that are not visible, making accidental movement of the pest a major concern.

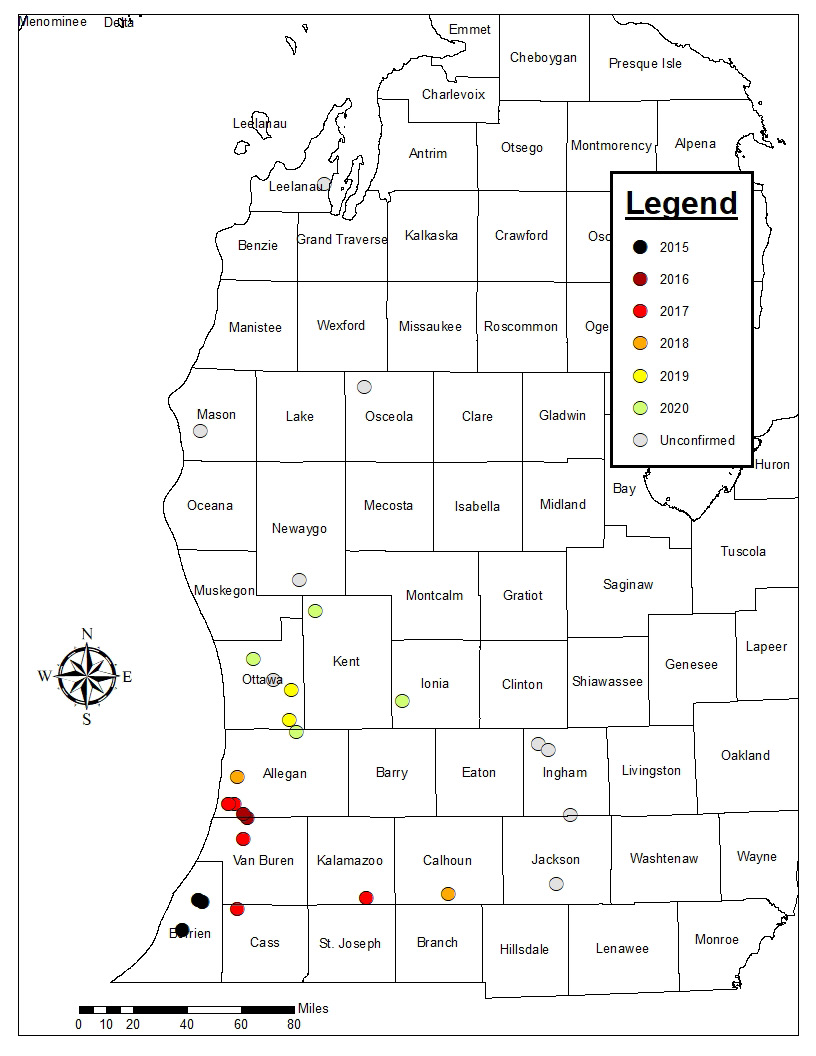

In an attempt to prevent ACGW from moving into Michigan, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development issued an external quarantine in 2010 which restricted importation of all live Castanea spp. material (except nuts) from states with known ACGW infestations. Despite this effort, ACGW was detected in two chestnut orchards in southwest Michigan in July 2015 and was subsequently found in eight more orchards by late August 2015. As of April 2021, ACGW had been found in chestnut orchards in at least six southwest Michigan counties.

Life Cycle and Identification

Asian chestnut gall wasp produces one generation per year and is a parthenogenic species. This means that all wasps are female and reproduction occurs asexually. Thus, even a single wasp can start a new infestation. Gall wasp adults are very small, about 1/8 inch (3 mm) long and have black bodies with yellow legs. Adult wasps lay eggs inside chestnut buds over a 4- 6 week period, typically extending from the last week of June to the second week of August in southwest Michigan. This period corresponds to approximately 1050 to 2100 cumulative growing degree days1 (GDD), (using a threshold temperature of 50 ºF [GDD50F] and a starting date of January 1). Eggs hatch after about 40 days. The tiny larvae remain dormant in the buds throughout the winter until the following spring. They are not visible at this time.

As leaves start expanding in spring around mid-May (300-350 GDD50F), the ACGW larvae begin to feed. Their feeding causes the plant to form small galls, 1/4 to 3/4 inch (5-20 mm) in diameter, on current-year shoots and leaves. Larvae feed and develop in chambers inside the galls throughout the summer. Each chamber contains a single larva. Most galls contain one or two chambers, but up to 20 chambers may be present in a large gall. Larvae feed for approximately four weeks, then pupate. The new generation of adult wasps begins to emerge in late June, just after trees drop their catkins. Adults continue to emerge and lay eggs for about six weeks.

Damage Caused by ACGW

While leaf galls usually have little impact, galls that form on current-year shoots can affect vigor and nut production of chestnut trees. Apical galls that form at the tip of shoots may be especially damaging. They reduce shoot elongation and can inhibit flower production, which reduces nut formation. Chestnut producers in Japan, Korea, several European countries and even some U.S. states, have reported yield reductions following ACGW invasion. Branch dieback has been observed in China, Japan, Korea, Italy and the U.S. when ACGW densities were high.

Management

An array of methods to control ACGW have been employed by commercial chestnut growers, with varying levels of success. Integrating strategies for managing ACGW should prevent yield loss while minimizing unnecessary pest control costs and impacts on beneficial insects such as pollinators and natural enemies.

Scouting: Effective pest management starts with active scouting. Chestnut growers in western lower Michigan, particularly south of I-96 and west of Highway 127, should be scouting their trees for evidence of ACGW during the growing season and in fall or winter, after leaf drop. In late spring and summer, green or reddish galls can be observed on branches or on leaves. In fall and winter, look for the dried, brown galls on the shoots. Many of the old galls remain on the tree through winter and are more visible after leaves drop in fall. These old galls can remain attached to the trees for at least one or two years after the wasps have emerged. If ACGW is present, it will be helpful to monitor gall densities and compare nut production between trees that are heavily infested and uninfested trees or trees with only a few galls.

Insecticide sprays: If galls are abundant and especially if nut production is low on heavily infested trees, you may need to control ACGW adults with a cover spray of a broad spectrum, conventional insecticide. If a cover spray is needed, correct timing and adequate coverage are essential. Correctly timing sprays is critical to ensure effective control of the pest and to minimize effects on an important biocontrol agent (see below) and beneficial pollinators. Insecticide sprays will have no effect on immature stages of ACGW that are protected within galls. In southwest Michigan, the first adult wasps typically begin emerging in late June (about 1050 DD50F) while the last wasps may not emerge from galls until mid-August (about 2100 DD50F). It is not necessary to control the very first wasps or the very last wasps of the summer, but you will want the insecticide on the trees before adult wasp activity peaks, around mid-July. Consider applying a cover spray with relatively persistent insecticide product around 1250 to 1350 DD50F, slightly before adult emergence and egg laying peaks.

Biological control: Classical biological control involves controlling an invasive pest with a natural enemy from its native range. This form of biocontrol has been successfully used to reduce ACGW damage in chestnut orchards in Japan, Italy and in other U.S. states. A tiny parasitoid wasp native to China, called Torymus sinensis (Kamijo), was initially imported into Japan in 1975. It successfully reduced ACGW densities in Japan and has since been released in Korea, several countries in Europe and the U.S. for ACGW biocontrol. There is no evidence that this highly specialized parasitoid has affected populations of native insects in areas where it has been introduced.

The T. sinensis parasitoid and ACGW share a long co-evolutionary history in China and the life cycle of the parasitoid is well synchronized with ACGW. In early spring, as ACGW galls are forming, T. sinensis adult females lay an egg into a gall chamber where an ACGW larva is feeding. Each parasitoid larva feeds on an ACGW larva within the gall chamber throughout the summer, eventually killing the ACGW larva. Parasitoid larvae remain inside the galls throughout the winter. As chestnut buds break and new galls form in spring, adult parasitoid wasps emerge from the dry, previous-year galls to oviposit within the green, succulent, current-year galls.

Fortunately, the T. sinensis parasitoid seems to have arrived in southwest Michigan at about the same time as ACGW and this beneficial wasp appears to be spreading. We monitored parasitism of ACGW by T. sinensis in four to seven Michigan orchards from 2017-2019. By 2019, T. sinensis was confirmed to be present in at least seven Michigan orchards where ACGW is established. In individual orchards, anywhere from 1 to 71 percent of ACGW larvae were killed by this parasitoid and parasitism rates generally increased over time. The important role of T. sinensis in reducing ACGW density highlights the need to correctly time insecticide cover sprays for ACGW or other insect pests.

Note: Old galls do not need to be removed! The beneficial parasitoids may still be developing inside the old galls. Removing those galls will have no effect on ACGW density but could reduce the beneficial parasitoid population.

Host Resistance: Chestnut species and cultivars vary in their resistance to ACGW. A few cultivars are highly resistant to ACGW, including 'Bouche de Bétizac' (C. crenata x C. sativa), an increasingly popular cultivar in Michigan orchards. 'Colossal' (C. crenata x C. sativa) chestnut trees, popular in Michigan due to their high yield and large nuts, are fairly susceptible to ACGW. 'Labor Day' (C. crenata), a cultivar often used to pollinate 'Colossal', produces nuts early in the season and is highly susceptible to ACGW.

Many cultivars of Chinese chestnuts (C. mollissima) have historically been planted in Michigan because of their resistance to chestnut blight. Chinese chestnut cultivars, which share a long co-evolutionary history with ACGW, are generally less susceptible to ACGW than Japanese or European cultivars, although susceptibility can vary even among Chinese cultivars. Moreover, chestnut growers in Japan who converted orchards to resistant varieties of C. crenata chestnut after ACGW invaded were initially successful. Over time, however, ACGW populations adapted and now colonize varieties that were previously resistant.

While detection of the invasive ACGW in Michigan is not good news, practical and cost-effective management tactics can be used to prevent severe damage. Scouting to assess the abundance of current and previous galls can help identify where ACGW densities are relatively high. Monitoring yield is important to evaluate ACGW effects on nut production. The T. sinensis parasitoid seems to be spreading with ACGW and appears likely to play a major role in regulating ACGW populations in the long term. It will be important to apply insecticide cover sprays only when necessary and to time sprays correctly to avoid affecting the beneficial parasitoid population. When expanding an orchard and planting new trees, consider chestnut cultivars that offer some resistance to ACGW. Integrating these options should help minimize impacts of ACGW and protect the Michigan chestnut industry over the long term.

If you locate what you believe to be ACGW please contact MSU Extension Educator Erin Lizotte at taylo548@msu.edu for further assistance. For more information contact the Michigan Department of Agriculture, Pesticide and Plant Pest Management Division. Download the MSUE Bulletin E3457, Asian Chestnut Gall Wasp for more information.

1. Cumulative growing degree days can be found on the MSU Enviroweather website at https://www.enviroweather.msu.edu. Select a station(s) near your orchard to find current and projected GDDs. Be sure to use the Degree Days Base 50 ºF column. General information about using GDDs is available at: Growing Degree Day Information - Integrated Pest Management (msu.edu).

Lesser chestnut weevil

The most important insect pest of chestnut trees in the central-eastern U.S. is the lesser chestnut weevil (Curculio sayi). Large chestnut weevil (C. caryatrypes) is also an important pest but is less prevalent. Lesser chestnut weevil has emerged as a significant pest in Michigan and growers need to be actively scouting for chestnut weevil. Lesser chestnut weevil are native and are host-specific, only infesting tree species in the genus Castanea (American chestnut, Chinese chestnut, European chestnut and chinquapin). Lesser chestnut weevil lays eggs on developing nuts, the larvae feed within the nut, compromising the kernel. If left unchecked, these weevils can infest and destroy the majority of nuts produced in an orchard. The natural range of chestnut weevil mirrors the natural range of American chestnut (Castanea dentata) in the Central and Eastern United States. When the American chestnut stands collapsed due to chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) the populations shrunk to small pockets of the U.S. where chestnuts are present. The prevalence of these pests in Michigan is unknown at this time, but weevil larvae have been found in chestnuts at harvest.

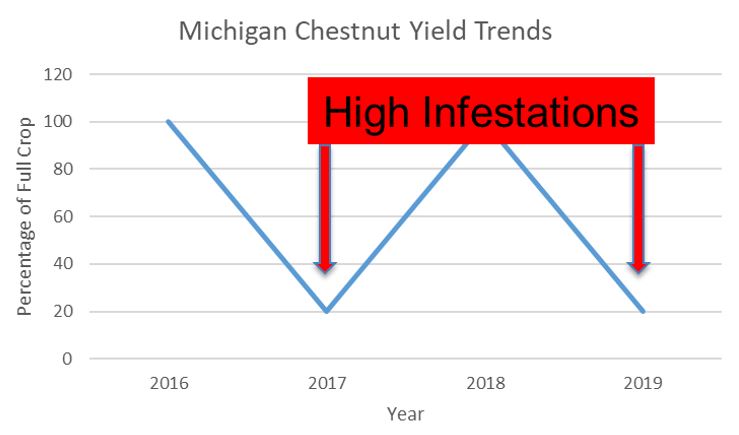

Over the last few years, Michigan chestnut producers have reported an increase in the number of larvae in nuts at harvest. It is likely that the observed larvae are immature chestnut weevils, though the exact weevil species has not been identified. During 2017 and 2019, some farms experienced high levels of weevil infestation at harvest. Affected orchards can be heavily infested, while other farms have effectively no larvae in nuts at harvest. At this time, chestnut weevil populations appear to be localized and cyclic in Michigan, with higher infestation percentages coinciding with low-yield crops, which generally occur on a biannual basis.

Lifecycle

It is important to understand the biology of chestnut weevil to effectively monitor and manage it on the farm. Lesser chestnut weevil adults likely emerge during two separate periods in spring around bloom (May-June) and early fall before burrs open (September-October). Spring populations feed on catkins while they are available. Once the catkins decline, the population disappears. It is unknown if they return to the soil or feed on other plants.

Eggs are deposited in the downy lining surrounding the nut as burs open and hatch in approximately 10 days, at which time the larvae feeds on the kernel and develops within the shell. After two to three weeks, the larvae chew a small exit hole and drop to the soil. Most overwinter as larvae, pupate in the soil the following fall and overwinter as adults. The total lifecycle is completed in two to three years.

Identification and Detection

Lesser and large chestnut weevil both have robust bodies and are dark brown or tan with brown mottling or stripes. Lesser chestnut weevil is ¼ inch in length, with a snout of equal or greater length.

Lesser chestnut weevil adult. Photo by Jennifer C. Giron Duque, University of Puerto Rico, Bugwood.org.

Scouting for chestnut weevils should begin just before bloom. Passive traps (circle traps on the trunk or pyramid traps, 1 per acre) can be used to capture ascending weevils, these traps should be set well before bloom occurs and checked twice a week. Scouting for weevils using a limb-tapping technique can also be done. Place a light colored sheet under the limb you are sampling and tap the branch with a padded pole or stick. Jarring the branch causes the weevils to drop from the tree onto the sheet. Weevils “play dead” when disturbed so don’t be fooled if they all appear dead, they will reanimate within a few seconds. Chestnut weevils are substantial in size and should be easily visible if present. Growers should sample at least 10 branches per acre. Scouting locations should include both the edges and interior of orchards as well as any hotspots that are identified.

Management

There are two primary goals in managing chestnut weevil. The first goal is to prevent larvae in nuts at harvest making their way to consumers; the second goal is to prevent nut damage from feeding. The four weeks prior to harvest are the most critical time for management, as eggs laid during that timeframe can result in larvae in the nuts at harvest. There are chemical, cultural and postharvest treatments available to control chestnut weevils. Ideally, a combination of cultural and chemical management techniques would effectively control the weevil in the field and eliminate the need for postharvest heat treatments, which can diminish quality and the marketable yield.

Cultural control through sanitation is the first step in managing chestnut weevil. Collecting and destroying nuts that won’t be harvested just after they drop can remove some developing larvae from the orchard. Insecticides should target the later windows of potential adult activity; August-September for large chestnut weevil adult emergence, and September-October for lesser chestnut weevil adult emergence. Do not apply insecticides during adult activity in May-June as bees are often foraging in the orchard at this time. Applying insecticide should only be made in response to significant weevil pressure and positive identification.

There are a number of factors to consider when selecting an insecticide for weevil control, including relative efficacy against other relevant pests like scarabs and leafhopper, known weevil efficacy in other crops, toxicity to beneficials, mode of action, preharvest interval and the number of applications allowed per season. Based on pest biology, the most critical applications for preventing larvae in the nuts at harvest occur in the four weeks before harvest and target adult weevils to prevent egglaying. Once larvae enter the kernels, insecticides will be ineffective. Chemical control for the entire period of kernel development will more thoroughly prevent damage, but may not be economically practical unless the orchard has experienced substantial weevil crop losses in the past. Check out the MSUE News for the most recent pesticide recommendations.

Thorough and frequent scouting is essential for optimal management, particularly with the lack of information regarding chestnut weevil behavior and prevalence in Michigan. Well timed applications, good sanitation practices and scouting will be the key to successful chestnut weevil management in Michigan.

Print

Print Email

Email