Bumble bees in greenhouse vegetable production

Commercial bumble bees have a life style and foraging behavior that is fitting for greenhouse operations.

Growing produce in greenhouses and hoop houses can be an effective and economical venture for early production of warm-season fruiting vegetables and for winter production of cool-season leaf and root vegetables. In addition, these structures are sometimes subsidized by state and federal agencies to support local four-season production of high-value crops. However, pollination of fruiting vegetables can be a challenge in enclosed structures.

Which fruiting vegetable crops work well in the greenhouse?

Cucumbers, watermelon, melon, summer squash, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant and beans are great greenhouse candidates for early summer production. Peas can be started early in these structures as well. For larger fruited vine crops, trellising can be utilized with mechanisms to support the weight of fruits (onion bags, panty hose, etc.). Bush type and vine type squash plants can be utilized with extra attention paid to spacing.

Which greenhouse crops require pollination assistance?

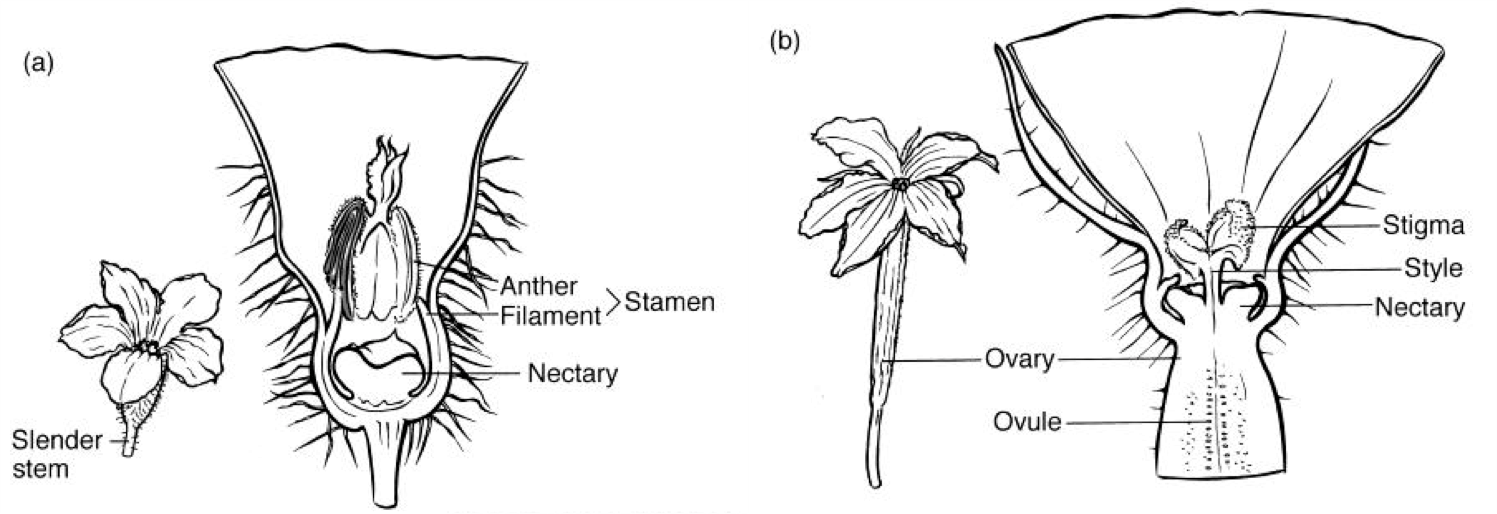

Standard cucurbits have separate male and female flowers, which require a pollinator to bring pollen from a male flower over to a female flower. Cucurbits naturally produce many more male flowers than female flowers to ensure bees come in contact with pollen while searching for the larger nectar pots in female flowers.

Breeding has created different flowering behaviors of these crops. Gynoecious cucumbers have been bred to produce predominately female flowers to maximize yield, but they require 15 percent interplanting with a conventional “sire” cucumber with the typical number of male flowers. Some seed companies will sell these seeds pre-mixed. Seedless cucumbers do not need pollination at all, and pollination will actually cause misshapen fruit.

However, the female flowers of seedless watermelon still need to receive pollen from a regular seeded diploid watermelon to trigger fruit set. Seedless watermelons require 30 percent interplanting with diploid “pollinizers” to maximize fruit set and yield. Often, a standard seeded watermelon is used as a pollinizer. Some muskmelons and cantaloupe cultivars can have self-fertile hermaphroditic flowers with both male and female parts, but still require a pollinator.

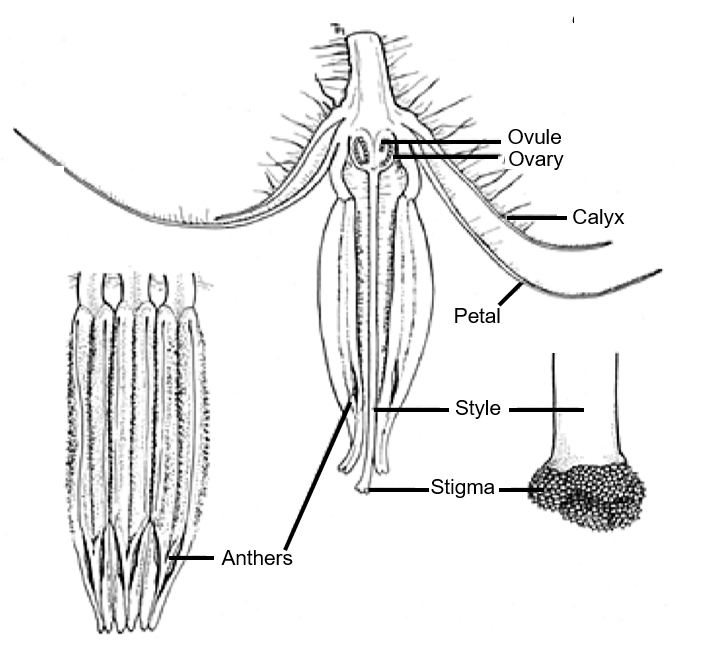

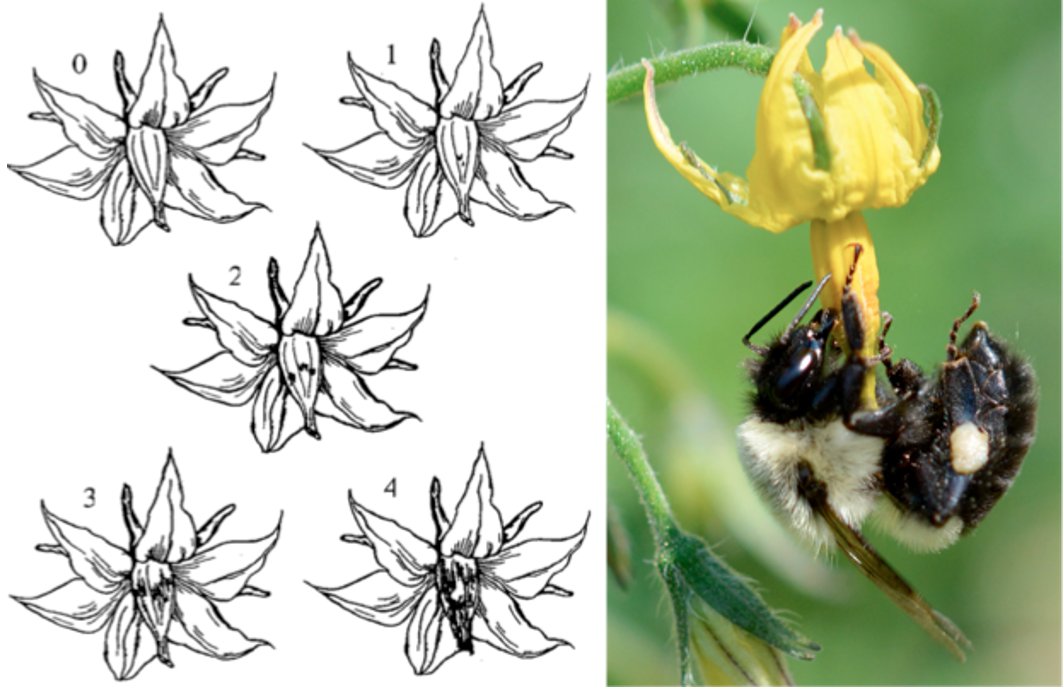

Some crop families have “perfect” flowers, meaning that male and female parts a co-located on the same flower, thus allowing self-pollination. Solanaceous crops are one crop family with perfect flowers; however, the tubular, downward-facing flowers need to be agitated to release pollen from the male part onto the female part. Though this occurs naturally by wind, pollination can be enhanced with mechanical vibration provided by growers or bees. Bumble bees do this particularly well with a technique called “sonication,” wherein they clamp onto the flower tube and flex their flight muscles to vibrate the pollen out.

Environmental conditions can greatly affect the quality and quantity of pollen release to the female part of the plant. Tomatoes and peppers need nighttime temperatures between 55-70 degrees Fahrenheit to produce pollen, and daytime temperatures should not exceed 90 F. Flowers will abort completely after 4 hours over 100 F. In addition, relative humidity should be between 50-80 percent to prevent pollen from being too dry to stick to the female part or too sticky to fall away from the male parts. Some parthenocarpic varieties exist that set fruit in cooler temperatures without pollen transfer.

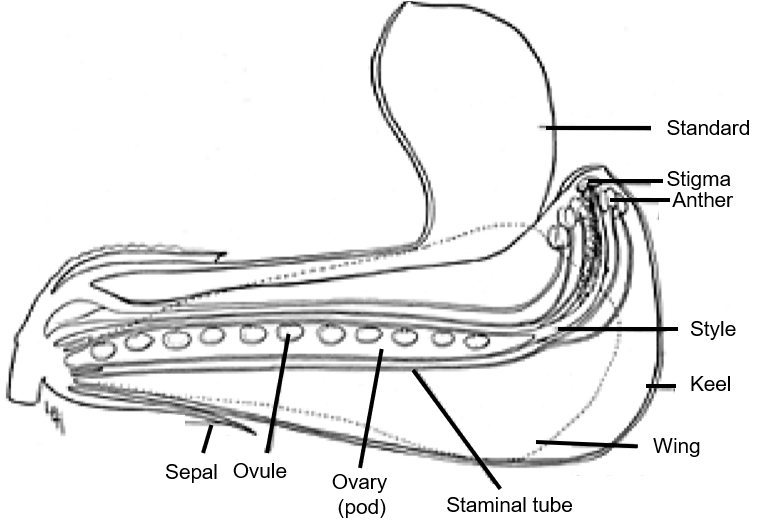

Beans are also perfect flowers, and lima beans fully self-pollinate before flowers open. But bees can boost yields of pole beans, snap beans and green beans and are necessary for setting pods in scarlet runner beans. Due to the complicated flowers of legumes, bees must learn to pollinate them.

Which pollinators are amenable to enclosed structures?

All bees can see ultraviolet light and use it for orienting to their surroundings, according to Adrian Dryer et al., 2011. This means the material of a structure can impact bee performance, and materials that allow the transmission of UV light are preferable if the crops grown need pollination from bees, as stated by Lora Morandin et al., 2002. Glass, acrylic rigid materials and polyethylene films all allow UV light through. Polycarbonate rigid materials and Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) films tend to block UV light. Additionally, additives are sometimes mixed with polyethylene plastics to block more UV to increase the life of the plastic and increase the residual activity of pesticides that would otherwise photodegrade, according to Heather Leach et al., 2017. Thus, UV-blocking coverings can impact pollination fruiting crops in two ways: by disorienting bees, and by potentially increasing insecticide exposure over time.

Artificial lighting during the winter months appears to significantly reduce bumble bee colony populations upon the colony’s introduction to the structures, as reported by Tjeerd Blacquière etl al., 2007. For example, in tomato greenhouses, the populations never do recover when reared under light from electric lamps, but eventually stabilize under ambient natural light. In pepper greenhouses, bumble bee colonies stabilize under light from electric lamps and recover with additional growth in ambient natural light. Winter management of these crops requires a balance of lighting to maintain colony strength or continual replacement of colonies.

Other factors that can impact pollinator foraging behavior are air flow and CO2 concentrations. Air flow can indirectly impact foraging behavior of bees by influencing the direction in which they fly. All flying species prefer to take off into the wind. Placing boxes in an area facing an on-coming breeze and facing the target crop can make their colony exits more efficient. CO2 concentrations have a debatable impact on pollinator behavior by impacting the growth characteristics of crop plants. In some cases, higher levels of CO2 above 350 ppm increased nectar volume, flower number or flower bloom longevity. Therefore, if bloom number, longevity or nutrition increases, then bees would likely be positively impacted.

Commercial bumble bees (Bombus spp) are the main pollinator inside structures in Europe and North America. Bumble bees live in much smaller colonies, making them easier to transport. Companies such as Koppert Biological Systems and Biobest have devised ways to rear them continually through the winter in greenhouse environments for seasonal production needs across the continent and have designed special packaging enabling them to be shipped through the mail with a food source. The bees are less aggressive than honey bees and are more acclimated to low UV conditions, as stated by Adrian Dyer and Lars Chittka, 2004. They are effective pollinators of vine crops and solanaceous crops inside and outside growth structures, but their colonies are short-lived (about eight to 12 weeks).

Growers can determine the visitation level of bumble bees on tomatoes and peppers by the bruising that occurs on the anther cone of the flower: the darker the bruise, the longer the visit and more effective pollination. Bumble bees have also been shown to successfully pollinate muskmelons in New Zealand greenhouses and are one of the most prominent wild pollinators of field-grown squashes.

Research by L.A. Morandin et al., 2001, suggests that one to three colonies per quarter acre of enclosed space is best for indoor pollination of vegetable crops. For a 30-feet by 48-feet, up to a 30-feet by 192-feet greenhouse, one bumble bee colony would be more than adequate for a tomato, pepper or vine crop. Colonies cost $135-$175 and contain approximately 75 foraging bees, which can increase to around 200 bees under good foraging conditions. A 12-week lead-time on bumble bee orders is appreciated by suppliers, as they raise colonies on demand.

If there are too few flowers in the greenhouse, the bumble bees will forage outside in summer to supplement their diet or repeatedly pollinate the same flowers in winter/early spring, which could possibly factor into over-pollination and blossom drop if you can rule out other environmental conditions that cause similar problems. Whenever possible, ask about the starting number of bumble bees in a colony and choose whichever is smallest for a single hoop house. You can also shut bumble bees inside their colony if you begin noticing deeply bruised flowers. Bumble bees can live off supplemental sugar water and honey bee pollen in their colonies until plants are ready for them. When more blooms are available, you can reopen the hive and can also plug the feeder to force bees out if needed.

Protecting bees and yourself

Spraying pesticides can harm bees through direct lethal effects (i.e., bee is instantly killed by pesticide) and indirect sublethal effects (i.e., bee is weakened by pesticide exposure and forages less). Many greenhouse vegetable producers apply systemic pesticides through hydroponic systems and use biological control for pest insect management.

If you need to use a foliar-applied pesticide to control a pest inside the greenhouse, follow label directions around bloom time and research which pesticides are higher risk for bees. Make sure to also confirm which pesticides can be used in a protected structure and if they require a respirator for their use.

Michigan State University Extension has a series of articles that can help make those decisions.

- Vegetable pesticide series: Should I use it during bloom?, April 17, 2018

- Vegetable pesticide series: Can I use it in the greenhouse?, March 16, 2018

- Vegetable pesticide series: Does it require a respirator?, March 16, 2018

Print

Print Email

Email