Situation Analysis Summary: Food security in the Omo-Turkana Basin

A summary of food security in the Omo-Turkana basin, from the Ambio situation analysis.

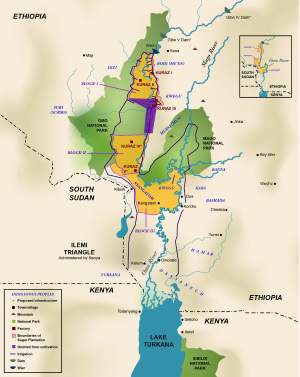

About 90 000 people comprising at least ten ethno-linguistic groups depend on flood-retreat farming for sorghum cultivation along the Omo – i.e. agriculture dependent on the annual flooding cycle, which deposits a layer of nutrient-rich silt beside the river, making the land productive for another year. See OTuRN Briefing Note #3 for further details on flood-retreat farming.

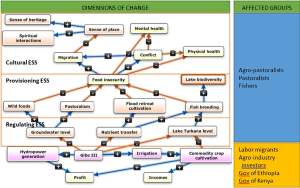

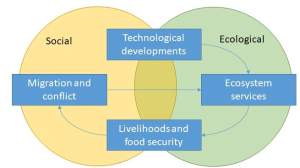

In the more southerly parts of the Lower Omo, the areas flooded by the river are larger, while the surrounding plains are dryer. This means that these southern populations are even more reliant on flood-retreat farming than their more northerly neighbors, who also practice rain-fed cultivation in the plains. All the indigenous communities of the region depend on livestock for their livelihoods (cattle, sheep, goats) but to different degrees. Within communities, extended families distribute labor to a diversity of livelihood strategies, including pastoralism, rainfed farming, and flood-retreat farming, in order to maximize access to both animals and crops. The river’s flood has also been important for livestock herding in the delta: it regenerates some of the most productive grazing land. For most of the region’s indigenous peoples, wildlife and wild plants are important supplements to the staple diets of sorghum, maize, and dairy products, and the riverine forests of the lower reaches of the river and delta area valuable resource for foraging, hunting, and honey production.

Since the end of the floods in 2015 (because of the Gibe III dam – see our ‘Hydrology’ blog), most populations in the northern part of the Lower Omo are entirely dependent either on rain-fed cultivation for crop production, making them highly vulnerable to drought, or on corporation-controlled irrigation systems. Reductions in the river flows downstream of the plantations are anticipated to reduce the availability and diversity of forage and thereby compromise livestock herding opportunities. Land clearance for sugar plantations has deprived wildlife of vital habitat and narrowed the portfolio of subsistence opportunities open to the people of the region.

Few scholars have studied the food security of other groups within the region, but household food security surveys conducted in 2013 among Bodi people both showed high levels of food insecurity among both groups. Site visits in the Lower Omo between 2016 and 2018 and ongoing communication between the authors and affected communities provide multiple lines of evidence for increased food insecurity, exacerbated by droughts affecting southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya. So far, social and economic impacts immediately around Lake Turkana are less pronounced than those in the Lower Omo, but the threat to the lake’s fisheries has serious implications for the food security of communities in Turkana, given the likelihood for reduced fish catch.

For further information, see the recently published paper “‘Do Our Bodies Know Their Ways?’ Villagization, Food Insecurity, and Ill-Being in Ethiopia’s Lower Omo Valley” by Edward G.J. Stevenson and Lucie Buffavand. Further food security research is also ongoing through the SIDERA project.

Dr. Edward G.J. (Jed) Stevenson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Durham University. His research interests include child development, water and food security, and development-forced displacement. Dr. Lucie Buffavand is a postdoctoral researcher of the Fyssen Foundation, affiliated with the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale, France, and research partner with the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Germany. Her research interests include the relation between social identity and place-making practices.

Print

Print Email

Email