Line drawn on the farm: FDA calls for end of antibiotic use for animal growth promotion

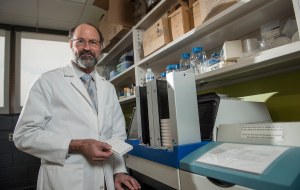

Daniel Grooms is helping veterinarians and livestock producers gear up for the changes that the guidance document presents to the industry.

Antibiotics, formidable assets for human health care, have similar applications in animal agriculture, where they are used to combat a range of serious infections caused by bacteria, such as bovine mastitis, enteritis and respiratory disease. Antibiotics have proven so effective in livestock that, for the past half century, they have been applied in low doses to animal feed and water even in the absence of disease for small gains in growth and productivity. That practice, however, is likely to end following a guideline issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2013.

Resistance to antibiotics was noted in animal agriculture as far back as 1951, when researchers found a streptomycin-resistant strain of coliform bacteria in turkeys. More cases, covering an ever-widening array of pathogens, have been reported since. Responding to growing consumer concern about antibiotic resistance, the FDA released Guidance Document 213 in an effort to eliminate the use of feed- and water-based antibiotics for livestock production enhancement.

The FDA has two major goals in combating antimicrobial resistance:

- Reduce the usage of medically important antimicrobials, those used in both human and animal medicine, in food-producing animals as growth and productivity promotants.

- Ultimately have all antimicrobial use for food-producing animals take place under the guidance of veterinarians.

Michigan State University (MSU) professor of large animal clinical sciences Daniel Grooms, who is also president of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners, is helping veterinarians and livestock producers gear up for the changes that the guidance document presents to the industry.

“Essentially what [the FDA] wants to do over time is eliminate the over-the-counter markets for antimicrobials,” the MSU AgBioResearch veterinarian explained. “Rather than producers getting them from a local feed store or ordering them from an online catalog, the FDA wants them all to be used under the supervision of veterinarians, who can prescribe them only for prevention or therapeutic reasons.”

In the document, the FDA requests that pharmaceutical companies remove growth or production claims from the product labels. The intent is to help reduce the amount of antimicrobials in the environment and thus slow the formation of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. The guideline, however, will not limit the availability of these drugs for therapeutic use on animals.

“Many of these drugs have more than one label,” Grooms explained. “One might say ‘mix in feed at a rate of 0.1 milligram per pound to increase livestock weight gain and improve feed efficiency’ — that’s a performance claim. It might also have disease control claims. Under the new guidance, the only one that the pharmaceutical company will remove is the one for growth promotion — the performance claim.”

The new guidance document will also eliminate the availability of feed- and water-based antimicrobials from over-the counter sources. Producers will have to go through a veterinarian to get a veterinary feed directive (VFD) to obtain feed-grade antibiotics for their animals.

“This is essentially the same as a prescription in human medicine. A veterinarian will have oversight over the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals,” Grooms explained. “He or she will have to write this VFD and can write one only for the prevention or treatment of disease.”

FDA officials have given the companies three months to declare whether they will follow the document and then an additional three years to incorporate the new product labels. According to Grooms, nearly all of the large pharmaceutical companies have already stated intentions to comply with the FDA recommendations.

Livestock producers examine options

Livestock producers will have to adapt to the new antimicrobial use landscape as well.“The producers that use antimicrobials for growth are going to have to turn toward other management strategies,” Grooms said. “It could be improved nutritional or environmental management or using other types of growth promotants, such as ionophores. The point is, there are management tools already available that producers can implement to make up for this void.”

Livestock producers will have to adapt to the new antimicrobial use landscape as well.“The producers that use antimicrobials for growth are going to have to turn toward other management strategies,” Grooms said. “It could be improved nutritional or environmental management or using other types of growth promotants, such as ionophores. The point is, there are management tools already available that producers can implement to make up for this void.”

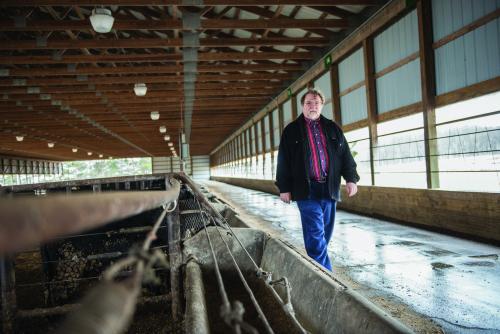

Dale Rozeboom, MSU professor of animal science and Extension specialist for swine nutrition and production management, said he views the changes in antimicrobial policy as an opportunity for positive growth within the animal agriculture industry.

“It will help farmers discuss the use of antimicrobials,” Rozeboom said. “I think that, together, the veterinarian and the farmer will be able to determine the judicious use of antimicrobials in order to protect the efficacy of the medically important ones and diminish the opportunity for resistance to them to develop.”

The more antimicrobials are used, the greater the chance that genes for resistance will be passed on to future generations of pathogens. This process increases the hardiness of their genes and reduces the effectiveness of drugs employed against them. According to Rozeboom, limiting the use of antimicrobials has opened the doors to exploring a range of new techniques — some that may be better suited to specific farm conditions — to be used on the farm to improve animal productivity.

“From a farm perspective, we’re thinking that there may be cases where farmers will be able to simply discontinue the use of antimicrobials,” he said. “There’s a whole range of management strategies and non-pharmacological additives that are available for farmers.”

Of the alternatives available, farmers will be able to select those that best fit the specific situations of their farms. According to Rozeboom, tactics such as adding zinc or copper microminerals, enzymes, probiotics, organic acids or herbal oils to animal feed have all shown promise in helping improve the productivity of livestock and could become more viable in the future.

Water is another possible means to deliver additives to the animals. Rozeboom and his colleagues recently completed a research trial in which dried egg yolk that contained antibodies for specific E. coli strains was added to the drinking water of young pigs to optimize their health. The egg yolk antibodies were produced by a private lab that inoculated hens with the pathogens. The hens then developed an immune response to the pathogens, causing antibodies for those pathogens to develop in their eggs. Results are being analyzed to assess the health benefits of this technique.

“There’s evidence showing that, in certain farm-specific situations, these techniques are effective to varying degrees,” Rozeboom said. “Not all environments are conducive to the same microbial populations, which is why it’s important to explore a range of possibilities. As an animal nutritionist, my job will be to collaborate with the veterinarians, who understand the farm health situation, and farmers, who want the best of both worlds in health and nutrition for their animals.”

Additives are just one way that farmers can improve animal productivity without antibiotics. Sanitation, climate control, weaning age and farm traffic are all important dimensions of the livestock industry that researchers are studying to improve animal health.

“We’re going to talk to farmers about sanitation protocols — specifically, what we call all-in/all-out sanitation,” Rozeboom said. “It’s a technique designed to break disease cycles on the farm by ensuring that rooms that have been cleaned are not immediately re-exposed to pathogens.”

Rather than emptying and cleaning only half a room of animals, the producer cleans and dries an entire room before new animals are introduced. This slows the spread of disease by preventing pathogens from jumping from the still-occupied side of the room and contaminating the newly disinfected one, Rozeboom said.

Improvements in ventilation and heating also stand to benefit livestock. In a project conducted last year, Rozeboom’s MSU Extension colleagues noted that reducing housing temperatures at night may actually improve animal health.

“We’re learning from the animals that cooling things off a bit at night not only conserves energy but may, in fact, be improving their growth and energy,” Rozeboom said. “Managing their environment is something to scrutinize as we go forward without antimicrobials.”

Another means of making up for the lack of antimicrobials for production purposes could come in adjusting the age at which animals are weaned. Currently, pigs are weaned between 19 and 21 days, but new research suggests delaying that to 24 or 25 days may help the animals be less susceptible to disease, Rozeboom said.

Improving biosecurity is an additional means of protecting farm animals. Preventing unnecessary traffic to and from the farm, keeping the feed trucks clean and knowing where they come from is one of the best ways to limit the spread of pathogens, Rozeboom said.

“These new regulations have opened up opportunities to explore other techniques and practices and take a more integrative approach to animal health and nutrition,” he said. “It’s not to say that antimicrobials have been misused; we’ve used them to the best of our knowledge. Now the FDA is challenging us to use them even more judiciously. I think farmers are up for that challenge.”

Industry concern focuses on an "even playing field"

With the passage and adoption of Guidance Document 213, producers will strive to maintain production levels without the use of antimicrobials to bolster animal growth. Both researchers and producers are confident in meeting this goal.

With the passage and adoption of Guidance Document 213, producers will strive to maintain production levels without the use of antimicrobials to bolster animal growth. Both researchers and producers are confident in meeting this goal.

“I was at the Michigan Pork Producers meeting in late February, and the producers responded [to Guidance Document 213] very favorably,” Rozeboom said. “I think they see it as a challenge; it doesn’t cause any fear or trepidation. They see it as a new approach in that the antimicrobial products aren’t lost. They’re still available in those serious [animal health] situations, which is what we all want because they’re very good for therapeutic and preventive purposes.”

Retaining antimicrobials to combat disease is a key concern of industry producers. It was the central theme in early research by Paul B. Thompson, MSU professor of philosophy and Kellogg chair of agricultural, food and community ethics.

“The information we collected showed that livestock producers were quite concerned about losing antibiotics as a treatment against infections,” said the MSU AgBioResearch philosopher, referencing a survey of Texas and Colorado beef producers that he and his colleagues conducted 10 years ago. “One of the problems at that time was that the campaigns against antibiotic use were very broad-blanket approaches that wanted to ban all antibiotics. They were getting a lot of pushback from the livestock producer community, which wanted to be able to use antibiotics to treat sick animals.”

Rather than adopting such an all-encompassing approach to antimicrobial regulation, the FDA has recognized the importance of antibiotics for animal health. By eliminating over-the-counter markets and production-related label claims but continuing to allow access to the drugs for the treatment of disease, the agency has created a situation that industry, government and researchers can all accept.

“We found that producers would be willing to stop using antibiotics as a growth promotant if they could be assured that other people were going to stop using them, too,” Thompson said. “They saw this not so much as something really essential to their production, but that they’d be put at a disadvantage if some producers were able to use them and others weren’t. They wanted an even playing field.”

In the years since Thompson’s survey, the industry and the FDA have worked to ensure this equality. Scott Ferry, a Litchfield, Mich., dairy farmer and president of the MSU Extension and AgBioResearch State Council, said livestock producers have been taking the use of antibiotics very seriously.

“As an industry, we have significantly reduced our need for antibiotics,” Ferry said. “The appropriate use of antibiotics to help animals survive, to nurture and care for them, is something that’s important to all of us, so making sure our drugs remain effective for animal health is what matters most. The utmost care is being taken to ensure our food supply is always protected.”

Sam Hines, executive vice president of the Michigan Pork Producers Association, echoed Ferry’s thoughts.

“We will adapt reasonably well [to the new guidance document],” Hines said. “There aren’t a lot of antibiotics used in the pork industry that are also used in human medicine to begin with. The bottom line is that we’ve focused on this issue for a long time and we’ve eliminated most antibiotic residue already.”

The Pork Quality Assurance program, developed by the National Pork Producers Council in 1989, was the first industrywide effort to reduce antibiotic residues in pork products. The program, distributed by the Michigan Pork Producers Association and its counterparts in other states, has expanded to include farm assessments for animal welfare and has certified 59,000 pork producers and 16,000 farms. To become certified, producers must have an established relationship with a veterinarian, have a health management system for their farm, provide proper care and housing for their animals, and demonstrate responsibility in the storage and administration of animal health products, including antibiotics.

Jury still out on the impact

Antibiotic resistance has been a serious issue in both agriculture and human medicine for decades. Researchers, government officials and industry representatives are hopeful that the new FDA guidance document will help alleviate it.

“The evidence for antibiotic resistance is just overwhelming,” Thompson said. “I had an antibiotic-resistant infection last fall, and it was pretty frustrating. I had to go through four different antibiotics to find one that worked for this relatively commonplace illness, and while mine wasn’t serious, a lot of people are experiencing infections that are life-threatening.”

In the face of this problem, voluntarily sacrificing antibiotics for production is a small price to pay for the possibility of safeguarding against a greater threat. “The most recent estimate I saw is that, of all the medically important antibiotics used in feed and water for livestock, only about 10 percent have been used for performance,” Grooms said. “So really, only about 10 percent of antibiotics will be reduced by this document.”

Grooms and his colleagues are now working to help producers take advantage of alternatives for improving animal productivity in an effort to minimize the impact of Guidance Document 213. They are providing educational sessions such as the annual Great Lakes Professional Cattle Feeding and Marketing course and helping veterinarians prepare for the increased demand that producers will have for their services.

The terms of the guidance document do pose some new problems for producers, particularly in areas with limited access to veterinarians.

“We’re in decent shape here in Michigan, but there are portions of the Midwest and the Corn Belt where swine veterinarians are not very plentiful, and producers in those regions might have trouble getting the veterinary feed directives they need for antibiotics,” Hines added. “It’s a potential problem that we’re going to have to find a good solution to.”

The primary challenge to the document is whether the changes will be effective at improving the antibiotic resistance situation.

“A good case in point is what has happened in Denmark in the past 15 years,” Hines said. “When they stopped all subtherapeutic use of antibiotics, their use of antibiotics for therapeutic purposes went up. You can make the argument that this presents an animal welfare issue, and we in the industry would like to see more conclusive scientific evidence that this will help.”

This challenge remains unanswered.

“The jury is still out a little bit on how much of an impact these changes are going to make,” Grooms said. “If you look at the data from Denmark, it suggests that there really hasn’t been a change in antibiotic resistance in the public sector. Maybe it will be 10 years from now, but there hasn’t been a significant change yet.”

Substantial improvement or not, the changes are being instituted by the FDA. It is an attempt to tackle an issue with serious human and animal health repercussions, and with implications on the American food system.

“The big thing to understand, from the public’s point of view, is that our food supply is still one of the safest, if not the safest, in the world with regard to animal foods,” Grooms said. “We understand consumer concern and are always looking to improve our production practices, and this is one step we can take to improve on an already pretty safe system. At MSU we’re always looking for ways to help producers adapt without antibiotics and make that transition while still maintaining productivity and economic viability.”

Print

Print Email

Email