Little monsters under the microscope: Parasites in our Largemouth Bass

Add Summary

Joe Nohner is a CSIS PhD student who's studying largemouth bass, specifically how habitat helps baby largemouth survive and grow, and the socioeconomic factors that influence landowners’ habitat management choices. He's also a passionate fisherman who aims to understand the layers and layers of complexity to solve ecosystem problems. This is an excerpt from Joe's blog, Fishing for Habitat.

Nov. 2, 2015

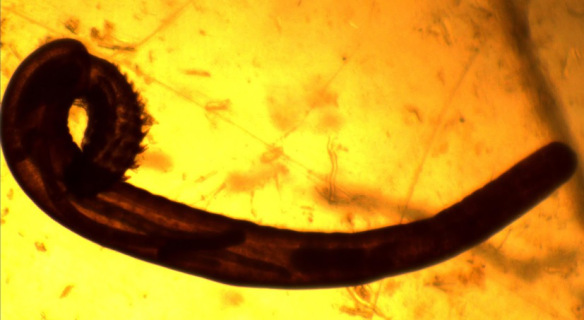

“I have no idea what this thing is, some sort of a spiny-headed worm or something,” called out Michelle, a technician in the lab. Transfixed by the insidious creature, she zoomed in with the microscope to take a closer look as she described what she saw. “It looks something like a small leech, but instead of a sucker it has a hardened front end with recurved spines.”

“Recurved spines?” I thought, sounds nasty! The little monster was a quarter of an inch long, but under the microscope it was clear that this animal meant business. It had clearly been shaped by evolution to do one thing very well: embed itself and never let go.

The thorny-headed worm, Acanthocephala, under our microscope. Recurved spines on the head (upper left side) enable it to remain lodged in the gastrointestinal lining of its host.

It was our first day looking through the stomach contents of young Largemouth Bass that we had captured this fall, and I was in the process of training each of the technicians on how to properly dissect the stomachs and identify their contents. I was used to seeing the normal diet items, such as zooplankton, aquatic invertebrates, and small fish, but I had never seen something like this!

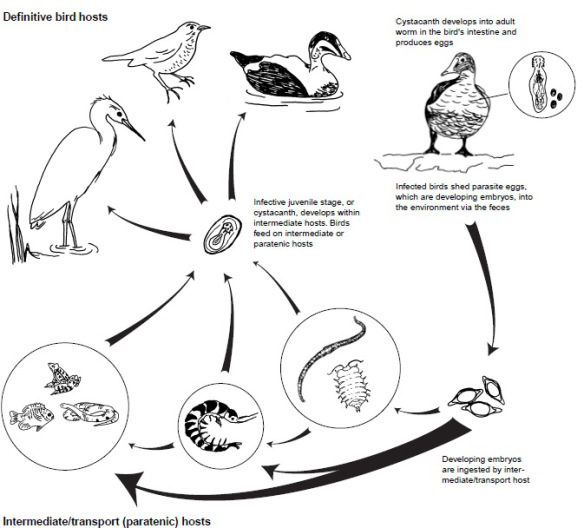

After poring over books and Internet resources, we identified the worm as Acanthocephala, literally “thornlike-head” in Greek. Acanthocephala have been found in humans, but this is extremely rare. Acanthocephala have a fascinating life history, in which they can potentially inhabit multiple hosts. Mature Acanthocephala produce eggs while living inside their preferred host, which is typically waterfowl such as ducks or geese. Therefore, the ultimate goal of most Acanthocephala species once the eggs hatch is to reach the stomach of an unsuspecting waterfowl host, but they may take a long and twisted path to get there. The eggs are excreted into the environment by the host, where small invertebrates such as scuds, isopods, or crayfish consume them. Instead of hiding in safe, dark places during the daylight hours as they normally would, scuds that are infected by Acanthocephala swim toward the light and up into the water column where they are more likely to be eaten by waterfowl or fish such as our young Largemouth Bass. If they are consumed by fish, they embed themselves into the fish’s intestines and absorb nutrients from food that the fish has eaten. The fish is an intermediate host; Acanthocephala is simply in a holding pattern waiting for the fish to be eaten. Once the host organism is eaten by a waterfowl, Acanthocephala will embed itself in the intestine, mature, and produce eggs.

Acanthocephala life cycle as represented by Friend and Franson 1999.

Print

Print Email

Email