Michigan hop scouting report – July 13, 2016

Twospotted spider mite populations are rising and miticides should be applied early in the infestation, before visible symptoms are widespread. Male hop plants are visible as growth becomes reproductive and should be removed.

As burrs develop around the state, male plants are easier to spot. Hop plants are dioecious, having separate male and female plants. Male hop plants are not desirable in the field as pollination causes the development of seeds in the female plants. Seeds lower the grade of the hops produced and also leads to the growth of unknown crosses in the field as they drop from cones into the hills below and germinate. If growers use rhizome cuttings from hills with plants of unknown parentage or train bines originating from these crowns, then uniformity and quality can be greatly diminished. The use of pre-emergent herbicides in established fields can help reduce this issue as they prevent seed germination.

Columbus, Tomahawk, Zues (CTZ) varieties are known to produce male flowers on female plants when under stress due to genetic differences. In these instances, the male flowers are usually sterile and the plant will also exhibit female cones. Typically, the plant does not need to be removed as it is incapable of pollination and seed production.

Growers have begun backing down the nitrogen rates, but will continue with enough to keep plants green and out of stress through harvest (about 5 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre, per week). For more information, check out the Michigan State University Extension article, “Hop fertility-nitrogen.” Aim applications have gone on and appear to have been very effective at burning back the lower portion of the bines and understory growth.

Twospotted spider mite populations are building in most hopyards, and many of the true miticides utilized for management recommend applications be made when population levels are low. True miticides have long residual control periods (six weeks or more), so growers are encouraged to apply miticides before populations expand and cause feeding damage. Feeding decreases the photosynthetic ability of the leaves and causes direct mechanical damage to the hop cones. Leaves take on a bronzed and white appearance and can defoliate under high pressure conditions. Intense infestations weaken plants, reducing yield and quality. The mites themselves also act as a contaminate pest.

Twospotted spider mites thrive under hot conditions, with the pace of development increasing until an upper threshold around 100 degrees Fahrenheit is reached. Conversely, cold and wet weather is not conducive to development. Twospotted spider mites are very small but can be observed on the underside of leaves using a hand lens. Growers can also look for movement to help them locate the mites. The eggs look like tiny, clear spheres and are most commonly found in close proximity to adults, webbing, cast skins and larvae. The larvae are small, translucent versions of the adults. Adults and some larval stages also have two distinct dark spots for which they are named.

When you are scouting, keep an eye out for beneficial, predatory mites that actually feed on twospotted spider mites. Predatory mites are often translucent, smaller than twospotted spider mites and move at a faster speed across the leaf surface. Predatory mites play an important role in balancing the twospotted spider mite population and should be protected when possible.

Leaf bronzing caused by mites. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Twospotted spider mite adults, larvae and eggs under magnification. Photo: David Cappaert, Michigan State University.

Growers should be scouting for mites season-long and make applications only when needed and as recommended by the miticide manufacturer. Some miticides are better positioned early in the season when mite levels are low, others are more effective in situations with high mite populations. For more information on twospotted spider mite management, refer to MSU Extension’s “Twospotted Spider Mite on Hop” fact sheet.

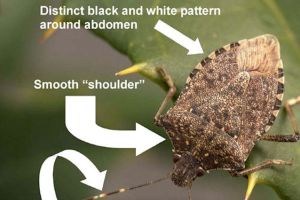

Japanese beetle activity continues around the state. Adult Japanese beetles aggregate, feed and mate in large groups after emergence, often causing localized damage. They feed on the top surface of leaves, skeletonizing the tissue between the primary leaf veins. If populations are high, they can remove all of the green leaf material from entire plants. Japanese beetle may also feed on other plant parts, including developing flowers, burrs and cones.

Japanese beetle on hop. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Japanese beetle feeding damage on hop. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Japanese beetles overwinter as larvae in the soil where they feed on grass roots and pupate into adults in early summer. Adults typically emerge in early June, feeding and mating throughout the summer. Adults lay eggs on turf from summer to early fall. Larvae hatch from the eggs about 10 days later and feed on grass roots. As temperatures drop in the fall, larvae migrate deeper into the soil to avoid the frost, moving back up to feed on grass roots in spring.

Visually inspecting the hopyard for Japanese beetles should be standard scouting protocol for growers. Due to their aggregating behavior and substantial size, Japanese beetles are typically easy to detect, but may be highly localized in the hopyard, requiring a thorough site inspection. Baited pheromone and floral traps are commercially available and may be useful to detecting emergence and severity. However, traps often attract beetles that may contribute to damage and are therefore not considered a commercially viable control option. At this time there is no established treatment threshold for Japanese beetles in hop. Growers should consider that established, unstressed and robust plants can tolerate a substantial amount of leaf feeding before any negative effects occur. Those managing hopyards with small, newly established, or stressed plants should take a more aggressive approach to Japanese beetle management, as plants with limited leaf area and those already under stress will be more susceptible to damage.

Japanese beetles feed on hundreds of different plant species, making them well-adapted to a variety of landscape types and more difficult to control due to their adaptability. When these generalist characteristics are coupled with their aggregating behavior, re-infesting damaged sites becomes a constant and frustrating management challenge for growers.

Japanese beetles are difficult to control and are most effectively knocked back with broad-spectrum insecticides, including organophosphates and pyrethroids. Unfortunately, due to their toxicity to beneficial mite predators, use of these broad-spectrum insecticides, particularly in mid- to late summer, can cause twospotted spider mite outbreaks. Research in fruit crops has shown that pyrethroid insecticides registered on hop, including bifenthrin and beta-cyfluthrin, have good contact activity against adult beetles, and can provide seven to 10 days of residual control. Malathion is an effective broad-spectrum organophosphate that is also registered for use on hop.

Based on research in fruit crops, it can take up to three days for malathion to take effect; it provides 10-14 days of residual control. Growers may also apply a registered neonicotinoid insecticide such as imidacloprid or thiamethoxam as applicable. Neonicitinoids are easier on beneficial predatory mites, but have been shown to contribute to increased pest mite populations by increasing female mite longevity and reproductive viability. Neonicitonoids should provide contact toxicity for two to five days, and residual anti-feedant activity against Japanese beetle adults based on efficacy trials in fruit systems.

Pesticides with organic labels include neem-based products like azadirachtin, which should provide one to two days of residual activity and good contact toxicity. Surround, a kaolin clay based particle film, has shown good efficacy against Japanese beetle in blueberry and grape plantings. Surround leaves a white, dusty film on the plant that acts as a physical barrier and irritant; therefore, it requires excellent coverage to be effective. Surround should not be used when cones are present as it can leave a residue on the cones through harvest.

To help mitigate the negative effects of insecticide applications on mite populations, growers should consider spot-treatments to heavily infested areas. Refer to “Pesticides registered for hop in Michigan, 2016” for more information.

Aerial downy mildew spikes are present in many hopyards at low levels. Basal spikes are no longer visible after Aim was used to burn back basal foliage. Downy mildew produces spores on leaf tissue, which then move onto healthy tissue and cause new infections. Growers are reminded that a protectant fungicide management strategy is needed to prevent new infections. Carryover from high infections last growing season will make a tight spray program critical to controlling downy mildew. For more information on downy mildew management, refer to “Controlling downy mildew on hop” by MSU Extension.

The downy mildew pathogen producing spores on the underside of a hop leaf. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Potato leafhopper activity continues in yards and symptoms are becoming more severe in untreated yards. Those who have already treated will want to scout carefully for re-infestation from surrounding areas as well as storms that move through the area. Damage to leaf tissue can cause reduced photosynthesis, which can impact production, quality and cause death in first year plants. Most injury occurs on rapidly expanding leaf tissue with potato leafhoppers feeding near the edges of the leaves using piercing-sucking mouthparts. Feeding symptoms appear as whitish dots arranged in triangular shapes near the edges. Heavily damaged leaves are cupped with necrotic and chlorotic edges and eventually fall from the tree. Severely infested shoots produce small, bunched leaves with reduced photosynthetic capacity. Symptoms of feeding damage are commonly referred to as “hopper burn.” For more information on potato leafhoppers, refer to the “Michigan hop scouting report – June 3, 2016.”

Adult potato leafhopper on hop leaf. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Potato leafhopper damage causing tissue necrosis around the leaf margin. Immature leafhoppers are also visible. Photo: Erin Lizotte, MSU Extension.

Don’t forget, all insects aren’t bad! There has already been a substantial amount of lady bug activity this spring. To learn more about these important pest management allies, read about natural enemies in the hopyard or visit MSU’s Biocontrol website. You can also register to attend the Supporting Beneficial Insects with Flowering Plants field day on Aug. 2, 2016, at the Clarksville Research Center, 9302 Portland Rd, Clarksville, MI 48815.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Agreement No. 2015-09785. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email