MSU Forestry Innovation Center explores maple sap through a One Health lens

Researchers across forestry, health sciences and microbiology are exploring new uses for maple sap beyond the syrup bottle, including as a hydration beverage for cancer survivors.

This story is part of a series highlighting MSU AgBioResearch’s work related to One Health, the concept that the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment is deeply related. MSU has created an initiative called One Team, One Health to promote university-wide efforts in this space. To view the full series, visit agbioresearch.msu.edu.

ESCANABA, Mich. — A forester, psychologist and microbiologist meet with each other in the woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. …

No, this isn’t the start of a sappy joke. However, the story about to be told is sappy.

Jesse Randall, director of the Michigan State University (MSU) Forestry Innovation Center (FIC), is working with a multi-disciplinary and multi-institutional team of researchers across the U.S. to study the One Health properties of maple sap.

The concept of One Health illustrates how animal, environmental, human and plant health are closely connected to and interdependent of each other in ways that are cross-disciplinary yet unified. It’s a strength MSU is tapping into as a university with its One Team, One Health initiative, and it’s something the MSU AgBioResearch-supported center has been incorporating in its mission since Randall took over as director in 2018.

“It starts with a team approach we’ve taken here at the center,” Randall said. “We’ve put together a world-renowned team of experts from Northwestern University and Montana State University. We were first in really the nation to have this idea that maple sap and maple syrup could be viewed beyond just something you put on pancakes.”

For David Victorson, a professor of medical social sciences and director of research at the Osher Center for Integrative Health at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, no project he’s worked on better reflects this idea than the one he’s doing in collaboration with FIC examining whether maple sap can be used as a hydration beverage for cancer survivors.

Originally from Escanaba, Victorson was familiar with FIC and friends with Randall, whose team helped him build a small sugar shack (a simple building where maple sap is processed and boiled down into syrup) at a cancer support center in the U.P. called the WALDEN Institute. This is part of a national nonprofit Victorson co-founded and leads called True North Treks, which supports young adult cancer survivors and caregivers through connection to nature and peers.

Beyond that effort, though, Victorson never considered how his nonprofit or integrative medicine research with cancer survivors could line up with the work being done at FIC — until one day.

“I was talking with Dr. Randall and he said, ‘You know there are these grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that focus on promoting education and research about maple products. I was wondering if you’d be interested in thinking about how we might connect some of our work around this,’” Victorson said.

Victorson told him he didn’t think there was much of a link between maple syrup and cancer survivors. That’s when Randall mentioned how in South Korea, more and more people are drinking maple water — the water that comes directly from the tree before it’s processed to become syrup — as a functional hydration beverage because it has similar electrolytes and nutrients that coconut water has, but with half the calories and half the sugar.

“And then a light bulb went off,” Victorson said.

Victorson shared with Randall that dehydration can be a significant problem during and following cancer treatment, which can result in unplanned hospital visits, increased complications and side effects, such as fatigue, anorexia, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting.

“Sometimes taste and smell receptors can become damaged from treatment,” Victorson said. “This, combined with the metallic taste of chemotherapy, can make drinking plain water difficult. That’s why it can be recommended to add a small amount of flavor, like fruit juice, to help. So, we already have a precedent for how this might be helpful.”

Victorson also shared that among cancer survivors, there’s a desire for ecologically sustainable, functional beverages that have less sugar and artificial sweeteners and more natural ingredients that can assist in hydration.

Maple drinks aren’t new. Canada, for example, sells UnTapped Mapleaid. But most people in the U.S. aren’t familiar with this type of drink, according to a national survey the team conducted with 100 young adult cancer survivors. And when the team had people try it in a formal taste test, Victorson said they were pleased.

“Like a wine tasting, we had over 50 cancer survivors view, smell and taste it, and it was very highly rated as a lightly sweetened, crisp and refreshing beverage,” Victorson said. “It didn’t taste like maple syrup to the surprise of many people. They said it was more like a lightly sweetened water.”

To date, Victorson and Randall have received USDA funding to work with food scientists to evaluate the nutritional properties of maple water and explore the drink’s potential as a functional hydration beverage in a controlled treadmill walking study.

“We have a lot to learn,” Victorson said when asked about the possible role maple water might take on for cancer survivors experiencing dehydration. “Even if maple water shows promise as a hydration solution, we’ll still recommend that cancer survivors drink water — lots of it — and when they don’t, we might recommend trying maple water.”

As this work has continued, more interdisciplinary collaborations have emerged. At the center of those connections, Victorson said, were Randall and FIC.

“Dr. Randall is the glue,” Victorson said. “FIC is the nexus of all this work.”

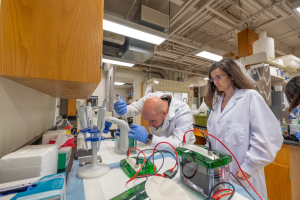

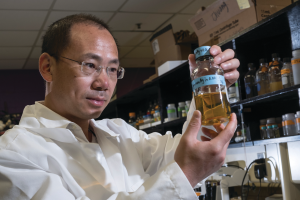

Through the center, Randall connected Victorson with Seth Walk, a professor of microbiology and cell biology at Montana State University, who could help answer questions about the maple drink such as: How should it be stored? How long will it last on the shelf? Does it have to be refrigerated or frozen? And so on.

Like Victorson, Walk had a previous connection to Randall: They were both doctoral students studying together at MSU.

“That goes right back to the strength of what MSU offers through its undergraduate and graduate mechanism,” Randall said. “I did my doctoral work at MSU, and so did Dr. Walk. It’s a lifelong partnership that we’ve built because of our graduate school connections.”

The work being done by Walk to understand questions about the maple drink at a microbial level are ongoing, and results are forthcoming.

In addition to this project, Walk is working with Randall in other ways to study how to manage microbes when collecting maple sap and producing maple syrup.

Randall said Michigan’s maple syrup industry has enormous potential to grow in the future, so research that advances how it’s produced is critical.

“When you look at Michigan’s forestry inventory and analysis data — especially in the U.P. — we sit here with tappable trees that are available, and that number is larger than all of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine combined,” Randall said.

“We are blessed with the Great Lakes. We are blessed with some level of a climate buffer, at least here in the U.P. Those who are producers on the fringe of the maple region are beginning to catch hold of the fact that Michigan is the future. We are the sleeping giant of the maple industry. They're coming here because they know they have at least their lifespan, and perhaps their children’s and grandchildren's lifespan, to set an operation up because of that buffer. So, we're helping producers at all levels. If they want to scale from 25 taps or if they want to start at 25,000 taps, we’ve invested in the systems that allow us to showcase both the research and the demonstration at those smaller scales and help them build up as they go.”

One area of research where Randall has teamed up with Walk is to find ways to transform low quality sap that’s usually produced toward the end of maple season and discarded by producers into a distilled spirit or other alcoholic beverage. They’re doing this by isolating yeast strains from this sap and identifying which ones could be used as an alternative to traditional types of yeast.

“That was the brainchild of Dr. Randall,” Walk said. “I didn’t know anything about that industry, but I did know a little bit about the microbiology behind it. So, it became a cool collaboration where he’s had the nose for how this could increase production and market value of the sap, and my team has been helping with the microbiology behind it.”

Another effort they’re jointly engaged in is reducing microbial biofilms in the maple tubes that collect sap. Walk said these biofilms, a community of microorganisms that stick to each other and a surface, can inhibit the collection of sap and create off-flavored and lesser quality maple syrup.

Walk said the pathogens that cause these biofilms are also common in the medical industry and can appear within catheters of all different uses. Taking what he’s learned from his research in that field — done in conjunction with the Center for Biofilm Engineering at Montana State University — and applying it to maple syrup production systems serves as another great example what it means to study through a One Health lens, he said.

“One of the major goals of One Health is to understand a problem by bringing in the knowledge gained from studying a similar problem in a totally different field,” Walk said. “We can address the types of things we see growing in these maple sap lines because of information we already know, either in biomedicine or other production environments such as the brewing industry.

“I’m learning things about engineering that I never knew, and I’m learning things about how leaves look under different spectra of light to make sense of whether a tree is healthy or not. I didn’t know any of that before. It’s fun as a scientist. The holistic view, I think, is a much more powerful approach to research than it is coming from any one discipline alone.”

Michigan State University AgBioResearch scientists discover dynamic solutions for food systems and the environment. More than 300 MSU faculty conduct leading-edge research on a variety of topics, from health and agriculture to natural resources. Originally formed in 1888 as the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, MSU AgBioResearch oversees numerous on-campus research facilities, as well as 15 outlying centers throughout Michigan. To learn more, visit agbioresearch.msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email