MSU researchers explore emerging market for mass timber in Michigan

Mass timber, engineered wood known for its strength and sustainability, has been used inside and outside of Michigan more frequently over the past decade to build and design large buildings.

East Lansing, Mich. — To see the future of how buildings are constructed in both Michigan and the U.S., you don’t have to travel far from Michigan State University. In fact, visit its campus and check out the newly built STEM Teaching and Learning Facility.

Opened in 2021 on the corner of North Shaw Lane and Red Cedar Road next to Spartan Stadium, the building represents a new wave of construction that’s becoming more popular throughout the country.

Mass timber buildings can go up quickly and efficiently, and they typically have a lower carbon footprint than comparable large structurers built with traditional materials. As more buildings have gone up, more people have taken notice.

MSU researchers create models forecasting the supply and demand of mass timber in Michigan.

As of June 2023, 856 mass-timber buildings in the country were under construction or had been built, and 1,004 were in design, according to WoodWorks – Wood Products Council, a nonprofit providing free project support and education for the construction of wood buildings. In Michigan, seven buildings were under construction or had been built and at least 29 were in design.

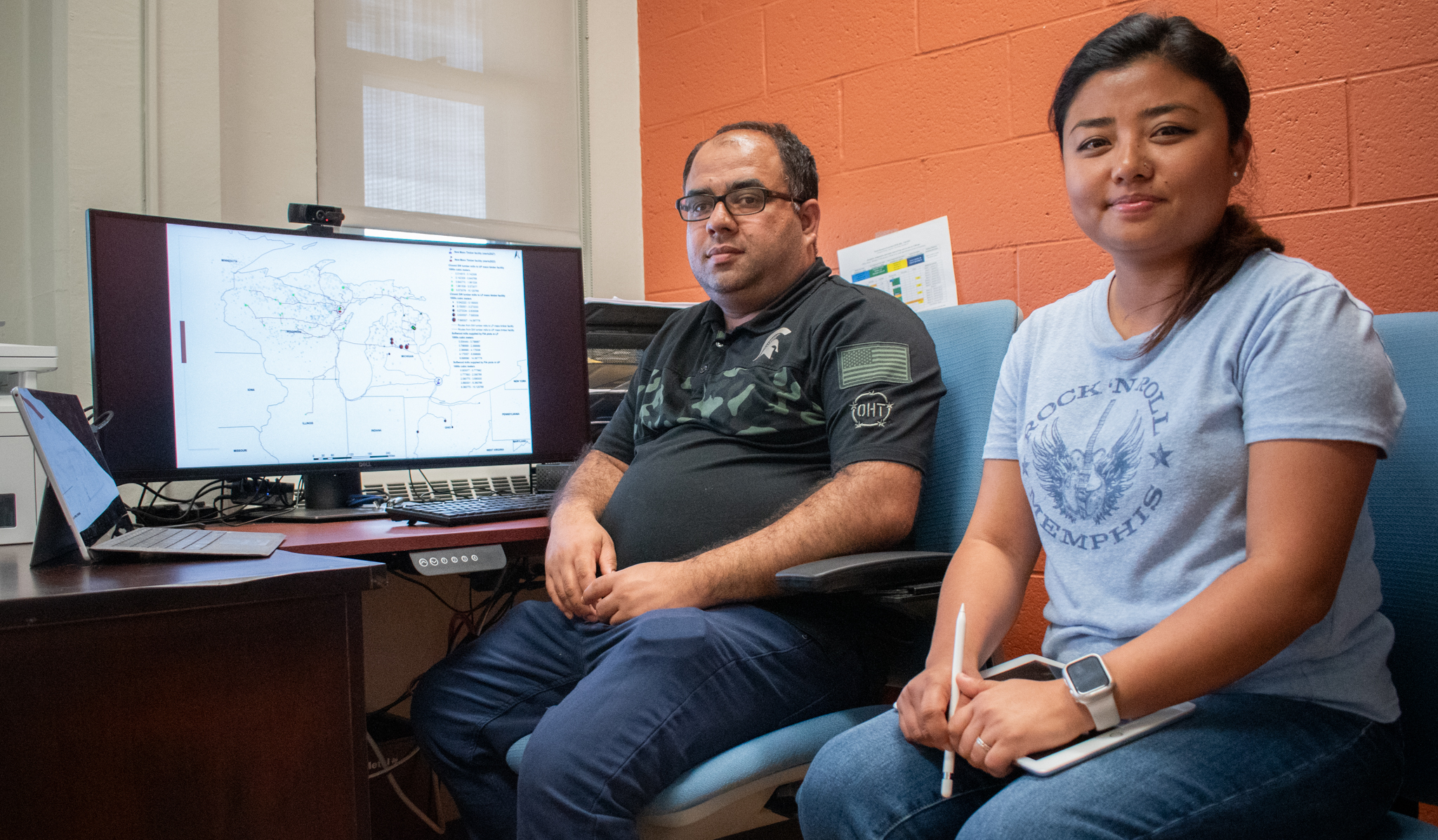

Raju Pokharel, an assistant professor in MSU’s Department of Forestry, is studying ways Michigan can employ its vast number of forests to capitalize on the mass-timber boom.

“Mass timber” refers to a variety of engineered wood products comprising dimensional lumber layered together to form panels, columns and beams. Common styles include: glue-laminated timber, where pieces of wood are glued together and each layer follows the direction of the wood’s grain; dowel- or nail-laminated timber, where pieces of wood are held together by dowels or nails and follow the direction of their grain; and cross-laminated timber panels, where pieces of wood are glued together and alternate the direction of their grain at each layer by 90 degrees — like a Jenga tower.

In 2021, Pokharel worked with graduate students and started developing models to understand what the economic impact would be in the state if a facility were built to produce mass timber.

Developed in Europe during the 1980s, modern mass-timber products started to gain traction in the U.S. around 2010. In 2015, the interest in mass timber began to grow in Michigan.

“People in Michigan were building with it — MSU built the STEM facility with it,” Pokharel said. “Instead of hauling and getting mass timber from Canada, why can’t we start a processing facility in Michigan? Michigan has wood, but it’s struggling to sell and use it optimally.

“Using wood means more revenue for landowners, which means better management of forests. When there’s money, forests can be managed better not just for timber, but for other benefits like water quality and wildlife habitat.”

Softwoods like spruce and pine are used for their strength, durability, hazard resistance and aesthetics to engineer mass timber. Pokharel said the International Building Code (IBC) doesn’t include hardwoods for mass-timber construction due to a lack of research and evidence on its performance and fire safety. Nevertheless, research on the engineering and fire-safety properties of hardwoods is currently being conducted with the hope that it’ll soon lead to its inclusion in the IBC.

Hardwood species make up about 70% of Michigan’s forests, but softwoods like aspen, pine and spruce also commonly grow in the state. However, building a mass-timber facility in Michigan means ensuring there’s an adequate supply of softwood lumber and guaranteeing the price remains competitive within the market.

Softwood sawmill operations, where lumber from trees is produced, are scattered across the Great Lakes region and within the state, many being in Michigan’s northern Lower Peninsula and Upper Peninsula. Softwood lumber is already used for construction projects that don’t involve mass timber, like building single-family houses, but by establishing a new mass-timber facility, the demand and competition for lumber would increase at sawmills.

The question became: Would there be enough softwood to meet an increased demand for it not only in Michigan, but across the country?

“Our analysis showed that there’s enough forest resources in Michigan and the Great Lakes states (to support a Michigan-based mass-timber facility),” Pokharel said.

Sandra Lupien is the project manager for this study. She’s the director of MassTimber@MSU, an MSU program that advances mass-timber construction and production in Michigan through outreach, communications, research, education, policy and partnerships.

With research funded by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR), Lupien, Pokharel, Emily Huff, an associate professor in MSU’s Department of Forestry, and Ichchha Thapa, a doctoral student in MSU’s Department of Forestry, estimated the market demand for mass timber.

In Michigan, several mass-timber building types are in the works: multifamily-residential, offices, schools — even a veterinary clinic. Because of the material’s large size, mass timber has — up to this point — not been typically used in constructing single-family houses.

“There’s a reason it’s called ‘mass’ timber — the pieces (of material) are massive,” Lupien said.

In 2022, Pokharel’s team estimated that the annual demand for mass timber in the Great Lakes states would be 12,400 cubic meters. Since then, the demand has projected to double until at least 2030. A preliminary analysis from Pokharel and Huff determined that the demand for mass timber in the Great Lakes states over the next five years will be at least 124,390 cubic meters, with the expectation that further analysis will see that figure increase significantly.

Thapa assists Pokharel and Huff in analyzing data on the supply and demand of mass timber based on models and surveys. In a recent survey, five groups of professionals were asked to provide answers to questions regarding their familiarity with mass timber, their thoughts about its application and their reaction to how it may impact their industries. Those represented by the groups were architectural engineers, foresters, local and state government officials, nongovernmental organization leaders and real estate professionals.

Pokharel said there are several questions those looking to invest want answered: Will the demand for mass timber be stable for the coming years, who’ll be the key players in generating its success, and what will the public perception of using it be?

So far, early results from the surveys conducted suggest a strong interest in mass timber, according to Pokharel.

“There’s definitely interest in and a positive vibe surrounding mass timber,” Pokharel said. “People like it, and because there are a lot of mass-timber projects within Michigan that are currently being developed, the idea we can produce mass timber in the state and sell it is being supported.”

Lupien, who regularly educates and engages with stakeholders, policymakers and the public on mass timber in Michigan, agrees that the idea of advancing it has been well-received.

“I’m trying to remember if I’ve ever had a conversation with a person about mass timber and had them say to me at the end, ‘That’s a bad idea,’” Lupien said. “People see the value. It’s beautiful. The material is durable. There are carbon, climate and sustainability benefits. There are potential economic benefits. There are biophilic benefits (characterized by a connection to nature).

“Usually, if somebody is holding out, you can bring them into a mass-timber building, and they’ll say, “OK, I get it.’”

There are no approved or planned projects for a mass-timber production facility in Michigan yet. Lupien said the goal of the supply-and-demand analyses is to provide prospective manufacturers with the insights they need to scope a mass-timber facility in the state.

By examining the locations of forests and sawmills in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, Pokharel and the team outlined two potential counties for a mass-timber facility to be built within Michigan — each strategically selected to capitalize on the supply of lumber from within and outside the state. Those counties were Menominee County in the Upper Peninsula, and Wayne County in the Lower Peninsula.

“Even if we’re producing mass timber in Michigan, it has a larger impact on forest management across all the states in the Great Lakes region,” Pokharel said.

What are the benefits of building with mass timber?

In talking with developers about mass timber, Lupien has noticed one aspect they commonly enjoy.

“Developers really like the biophilic benefits of mass timber,” Lupien said. “Biophilia is the idea that there are benefits to bringing nature indoors. Research has found that when we have materials like exposed wood in buildings, the occupants of those buildings report qualities like better mental health, a sense of well-being and greater productivity.”

People who seek out this type of environment, whether it be for occupation or residency, are willing to pay extra for it, Lupien said. This is an intriguing economic prospect for developers.

Another economic benefit of mass timber is the jobs it would generate.

From 2022 data that showed an annual 12,400-cubic-meter demand for mass timber in Michigan, Pokharel said there’s the potential for about 90 jobs to be created. Thirty-five jobs would be directly connected to the mass-timber facility, 31 jobs would be indirectly linked to businesses (like sawmills) that contract with the facility, and 24 jobs would be induced by the facility to support businesses (like restaurants) that may see an uptick in patronage due to the facility’s location.

Pokharel said because demand for mass timber is projected to double each year until at least 2030, job numbers are also predicted to increase as a result.

In relation to other construction material, mass timber — which arrives on site as a prefabricated kit of parts — can be more efficient to build with. This can result in shorter project timelines, allowing construction teams to take on more projects.

Lupien said the team of architects, engineers, managers and installers that assembled the MSU STEM building had previously never used mass timber. There was a learning curve, but they told her by the end — if they knew from the beginning what they’d learned — they could’ve trimmed the project’s timeline by weeks. She said all the companies involved have sought new mass-timber projects.

There are also environmental benefits to utilizing the material.

Mass timber emits less greenhouse gases to source, manufacture and transport compared to nonrenewable materials, like concrete and steel, brought about by fossil fuels. Additionally, because trees store carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, mass timber keeps carbon locked inside its wood rather than escaping into the atmosphere through other processes.

The MSU STEM building is comprised of 3,000 cubic meters of mass timber and stores at least 1,856 metric tons of carbon dioxide, according to Lupien.

“Who cares about that pretty abstract number?” she asked. “But when you say, ‘That’s like not driving the average car about 4.7 million miles or not burning about 2 million pounds of coal,’ people start to care.”

Using mass timber places an added value on the forest. It incentivizes people not to cut down forests for other land uses, and it encourages a higher harvesting rate to gather more wood — a practice Lupien said would help keep forests healthy and continuously growing for future generations.

“Something that I find energizing about working in the mass-timber industry is the high level of collaboration across different sectors,” Lupien said. “It’s a network in which the forest-product professionals, all the way through to the mass-timber installers, overlap with each other on at least some part of every project.

“The people who work in the mass-timber space see the landscape (of the industry) in a holistic way. We’re thinking about where the wood is coming from, how it’s being put into a building and what to do with it when it’s time to dismantle a building.

“It’s exciting to see so much holistic thinking, innovation and collaboration in an industry.”

Michigan State University AgBioResearch scientists discover dynamic solutions for food systems and the environment. More than 300 MSU faculty conduct leading-edge research on a variety of topics, from health and climate to agriculture and natural resources. Originally formed in 1888 as the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station, MSU AgBioResearch oversees numerous on-campus research facilities, as well as 15 outlying centers throughout Michigan. To learn more, visit agbioresearch.msu.edu.

Print

Print Email

Email