Red meat trade serves up global health woes

Red meat is being exported to countries, bringing along increased health problems.

Globally, - especially in developing countries -- an order of red or processed meat comes with heaping sides of ill health. A group of Michigan State University (MSU) scientists have linked a booming meat trade to critical roadblocks for sustainable diets.

In this week’s BMJ, Global Health, scientists found that the red and processed meat trade – beef, pork, lamb and goat, as well as red meat processed by smoking, salted, or curing – is playing a substantial role in balancing nutrition and meat availability across the world. In many developing countries, eating more red meat is a hallmark of newfound prosperity.

Unfortunately, the researchers have found, so is a substantial rise in non-communicable diseases such as colorectal cancer, type-two diabetes and coronary heart disease. Understanding the true global costs to both human health and the environment are crucial if countries are going to achieve sustainable diets.

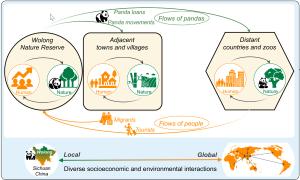

“Trade is about more than economic benefits,” said Jianguo “Jack” Liu, MSU Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability and director of the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability. “As foods move over distances, various consequences also show up in distant places. It is essential to understand what happens to people’s health when a shipment of meat arrives in a new place. Examining the true costs of meat consumption through telecouplings such as trade can help avoid or minimize counterproductive consequences.”

The group used a risk assessment framework to compare where and how much of the red and processed meats were traded across 154 countries over 25 years. They compared this to the rates, of three chronic diet-related health problems at the same time, 1993 – 2018, to determine what health effects could be attributed to meat trade and which countries were particularly vulnerable to these health problems.

What they found was rates of change in disease twice as high in developing countries compared with developed countries as new prosperity and urban growth translated to meals of imported meat. Particularly vulnerable to diet-related disease and death were island countries in the Caribbean and Oceania. Countries in northern and eastern Europe also found diet-linked disease and death soaring as red and processed meats from across the world ended up on their plates.

These rapid increases are partly because many of these countries, such as Slovakia, Lithuania, and Latvia, joined the European Union (EU) between 2003 and 2004, and regional trade agreements for goods among EU members greatly accelerated meat imports to these countries with economic benefits.

“Our findings suggest that both exporters and importers must urgently undertake cross-sectoral actions to reduce the meat trade’s health impacts,” said author Min Gon Chung, who received his PhD at MSU and now is a postdoctoral researcher at University of California, Merced. “To prevent unintended health consequences due to red and processed meat trade, future interventions need to integrate health policies with agricultural and trade policies with both responsible exporting and importing countries.”

The paper also suggested that since the World Trade Organization brokered regional trade agreements to accelerate the flow of red and processed meats, strengthening collaborations to likewise make health agenda regulations more robust.

Last October, Chung and Liu published another paper in Scientific Reports that outlined for the first time the underlying forces driving these dietary changes to better understand the unintended social and environmental consequences of a world that eats more meat.

In addition to Chung and Liu, the BMJ Global Health paper “Global red and processed meat trade and non-communicable diseases” was written by CSIS PhD candidate Yingjie Li. The work was funded by the National Science Foundation, NASA, Environmental Science and Policy Program at MSU, and the Sustainable Michigan Endowment Project.

Print

Print Email

Email