Small farmers sink or swim in globalization’s tsunami

From a synthesis of 12 cases, researchers found when smallholder farmers are connected to faraway systems, the key is to empower them to higher agency and more livelihood opportunities.

Whether small-time farmers across the world get swept away by globalization or ride a wave of new opportunities depends largely on how much control they can get, according to a new study that takes a new, big-picture look.

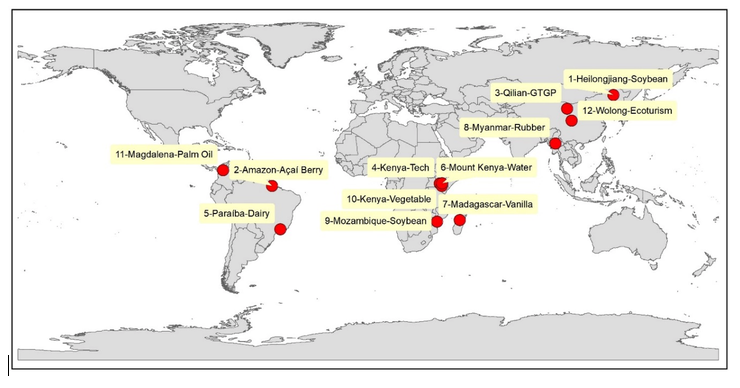

From soybean farmers in China to those who grow vanilla in Madagascar, trendy açaí in the Amazon or rubber in Myanmar, their place in new, fast-paced markets that can be both regional and global isn’t fully understood until examined in context with its partners and competitors near and far. Scientists at Michigan State University (MSU) and across the world take a new look in “Understanding How Smallholders Integrated into Pericoupled and Telecoupled Systems” in this week’s journal Sustainability.

The takeaway: It’s agency – the ability these farmers have to seize some control to better their position in a global market.

“Given that smallholder farmers everywhere are critical to several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, such as ending poverty and hunger, we need to fully understand how being swept into global markets affects them, and that means not just looking at their bottom line, but how they interact across the entire market process,” said Jianguo “Jack” Liu, MSU Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability. “We found success applying the integrated framework of telecoupling – which allows us to look at both human and natural systems across distances – to reveal some surprising truths.”

The group looked at 12 cases of smallholder farmers. Some, like farmers in Kenya, were struggling to grow more  corn amidst water shortages. Others, like soybean farmers in China, found themselves at the mercy of enormous markets dominated by Brazil and the United States. Vanilla growers in Madagascar are pummeled by volatile prices while açaí berry growers in the Brazilian Amazon Delta found opportunity in the big cities to sell their newly popular crop.

corn amidst water shortages. Others, like soybean farmers in China, found themselves at the mercy of enormous markets dominated by Brazil and the United States. Vanilla growers in Madagascar are pummeled by volatile prices while açaí berry growers in the Brazilian Amazon Delta found opportunity in the big cities to sell their newly popular crop.

In each case, these smallholder farmers have traditionally been considered passive to external pressures – swept along the fierce tide of globalization. But as Yue Dou, a former CSIS research associate now at the Institute for Environmental Studies in Amsterdam, notes following that flow paints a more nuanced picture.

“Globalization is not the only way that integrates smallholder to the world,” Dou said. “Smallholders also send or receive flows other than agricultural goods, such as labor migration, water discharge, and technology exchange. Some of these various connections are with faraway markets, while some of them are with their neighboring villages and towns. And they co-exist. The telecoupling framework allows us to investigate the various ways smallholders connect with the world, shedding light on the agency of decision makers and potential paths to improve the environment and economics within the system.”

The paper examined how some açaí growers rode the new popularity of their crops to new lives by taking second homes in nearby cities which had better job and education opportunities. The Kenyan farmers found benefits in new partnerships with the Chinese, who shared new mulching systems that helped them save precious water and increase corn yields.

Others struggle to grasp control. China’s soybean farmers in the northern Heilongjiang Province have little ability to control global soybean prices and are forced to make decisions about what they plant on the basis of these forces, decisions that have environmental consequences as they are forced to plant crops requiring more fertilizer.

“We found that if the main linkages smallholders have is with their neighbors and not the distant world, they may have more choices of livelihoods and better overall outcomes in the economy, social well-being, and the environment,” Dou said. “When smallholders are connected to faraway systems, the key is to empower them to higher agency and more livelihood opportunities. Sometimes this can be improved by creating additional connections to neighbor systems.”

Besides Liu and Dou, the paper was written by Ramon Felipe Bicudo da Silva, Paul McCord, Julie G. Zaehringer, Hongbo Yang, Paul R. Furumo, Jian Zhang and J. Cristóbal Pizarro. The work was funded by the National Science Foundation, Michigan AgBioResearch; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

Print

Print Email

Email