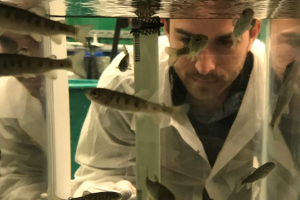

Studying how an infectious disease-causing pathogen thrives in the environment

MSU infectious disease researcher Eric Benbow is using a $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation to study Mycobacterium ulcerans, a pathogen that causes infectious disease and flourishes in tropical regions.

When the novel coronavirus pandemic grabbed the world’s attention in 2020, causing widespread illness and disrupting daily life, many scientists were left scratching their heads.

On top of dealing with the bevy of unknowns surrounding COVID-19 and its short- and long-term health implications, they were scrambling to figure out how to safely continue their ongoing research.

For M. Eric Benbow, an associate professor in the Michigan State University Department of Entomology investigating infectious diseases, the new reality hit home.

“Obviously the coronavirus has received a ton of attention from the general public and the scientific community for good reason, but that doesn’t mean other infectious diseases have stopped,” said Benbow, who also has an appointment in the MSU College of Osteopathic Medicine. “For those of us doing research on these other diseases, it really emphasizes how important this work is to preventing pandemic-level spread.”

In June 2019, Benbow and a team of international researchers secured a $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation to study Mycobacterium ulcerans, a pathogen that causes infectious disease and flourishes in tropical regions.

The disease triggered by M. ulcerans is called Buruli ulcer and affects skin, soft tissue and bone. Although typically treatable, if detected late in its progression or left untreated, Buruli ulcer may result in permanent scarring, disfigurement or disability. According to the World Health Organization, the illness has been detected in 33 countries, with West Africa being hit hardest.

“We know very little about how this pathogen moves around in the environment,” Benbow said. “Additionally, we need to understand more about how M. ulcerans interacts with other microbes and pathogens. This work can help us uncover basic information about how diseases become emergent and spread.”

While there is no consensus among the scientific community on how Buruli ulcer is contracted, Benbow said there is a hypothesis on why M. ulcerans is so successful in tropical environments.

The project is testing the novel weapons hypothesis, which suggests some invasive species are dominant in new ecosystems because they contain compounds that allow them to prosper at the expense of native species. Scientists have confirmed this in plants and believe the same could be true for microbial communities — especially those in the environment such as M. ulcerans that cause disease.

A co-principal investigator, Jennifer Pechal, an assistant professor in the MSU Department of Entomology, brings expertise in genomic and computational tools to examine how microbes and insects effect human and animal health.

The initial plan called for the team to visit French Guiana, a district of France on the north Atlantic coast of South America, in 2020. Benbow said during the initial trip, the team would scout watershed areas and figure out navigation of waterways. A second journey would include the start of sample collection of fish, invertebrates and biofilms that grow on aquatic plants.

French Guiana was chosen because Buruli ulcer is endemic in the region, giving scientists a unique chance to explore the issue with French colleagues, including a co-principal investigator Jean-François Guégan, a research professor at the French Institute for Research on Sustainable Development.

But the coronavirus altered those plans. Travel restrictions forced collaborators to meet virtually to discuss a new path. French Guiana will still be the principal location for the project once it’s deemed safe to venture there, but in the meantime, researchers wanted to make progress. This included creating online resources using Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and a website to promote the project.

“Once we talked about it, we realized we could do sample collection right here in the U.S. we previously didn’t have time for or wouldn’t be able to do if we were in French Guiana,” Benbow said. “We knew of a published paper that suggested M. ulcerans may be present in the U.S., with that team using molecular markers. We have student support and resources, and two of our co-principal investigators, Heather Jordan and Michael Sandel, are near the region we want to test.”

Benbow received permission to travel with a team to collect samples in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. Sandel, an assistant professor at the University of West Alabama, is evaluating the evolution of fish hosts and mycobacteria such as M. ulcerans. Jordan, an associate professor at Mississippi State University, has screened the samples for the pathogen, revealing promising early results.

“We’re not certain we’ve found it yet,” Benbow said. “But if it’s not M. ulcerans, it suggests that at least the toxin, mycolactone, is in the U.S. and could possibly affect several communities, from humans to other animals and microbes.”

Researchers believe U.S. strains may not be as virulent for humans as those in Africa due to differences in interaction with bodies of water. In Africa, manual labor and agricultural practices leave people more susceptible to skin injuries in which infections can more readily occur. Benbow said one of the major questions is figuring out how those strains have evolved to become more virulent and, therefore, more dangerous.

Jordan will be screening again to include detection of strains of the toxin found in French Guiana and Mexico. These findings will eventually be compared with those from French Guiana to determine similarities in concentration or potential to cause disease in humans, animals or other organisms.

“The strains in the U.S. may not be as virulent for humans,” Jordan said. “They could be virulent for other animals such as other mammals, fish or amphibians, however, and pose a significant threat to wildlife.”

Print

Print Email

Email