Three students earn USDA NIFA predoctoral fellowships

Kaitlyn Casulli, Genevieve Hoopes and Natalie Kaiser, doctoral students conducting research with CANR faculty, are among 57 award recipients nationwide.

Kaitlyn Casulli, Natalie Kaiser and Genevieve Hoopes, doctoral students conducting research with faculty in the Michigan State University (MSU) College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, have been awarded fellowships from the U.S. Department of Agricultural National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA NIFA). Recipients are recognized for their many talents and innovative approaches in research, education and outreach.

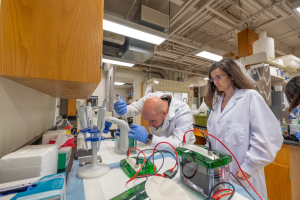

Kaitlyn Casulli

Casulli, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biosystems and Agriculture Engineering (BAE), is studying how dry roasting peanuts can reduce pathogens, such as Salmonella, to better understand the risk of contracting foodborne illness.

Kirk Dolan, professor in BAE and the MSU Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, is one of Casulli’s advisors, along with Donald Schaffner, professor of food science at Rutgers University. Bühler, Inc., an industrial solution provider for food and mobility, and one of their customers, Mana Nutrition, are serving as commercial testing sites.

“We are currently getting a better idea of the rates at which pathogens can be reduced in dry foods, but we are missing the link between what we are doing at the lab scale and what is happening at the commercial scale,” Casulli said. “We are able to tightly control lab-scale roasting experiments and measure multiple variables with relative ease, but commercial-scale roasters are essentially a black box. We verify their ability to produce a uniformly safe product based on inputs and outputs, without real-time tracking of what’s happening to a product when it’s roasted in a potentially variable process.”

She focuses on examining impacts of thermal variability on pathogen reduction, with a particular emphasis on producing a safe peanut-based product to address malnutrition in developing countries.

“While foodborne illness in a developed nation most often looks like being sick for a little while (think a 24-hour bug), in a developing nation for an already malnourished person, the health consequences can be much greater,” she said. “We need to balance providing a severe enough heat treatment to reduce foodborne illness risk, while not heating the product to the point of destroying nutrients.”

Casulli said it’s an honor to receive federal recognition for her research, and she’s excited to see where it takes her.

“Beyond this recognition, I am excited for the chance to begin creating a body of work that is uniquely my own, an opportunity not often presented to Ph.D. students who work on projects their advisors conceived,” she said. “This fellowship will also afford me the opportunity to broaden my perspectives beyond the lab, such that I may be better prepared to address societal challenges in future research and mentoring opportunities.”

Natalie Kaiser

Kaiser, a Ph.D. candidate in the MSU Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences’ Potato Breeding and Genetics Program, works to develop potato varieties that are resistant to the Colorado potato beetle, an herbivore pest that is incredibly destructive to potatoes.

“Controlling the Colorado potato beetle is particularly difficult because it has a remarkable ability to become resistant to the insecticides available to growers,” she said. “Developing Colorado potato beetle resistant varieties offers a powerful tool to manage this pest, reducing the economic burden to growers and the environmental impact of sustained insecticide use.”

Kaiser studies wild potatoes that produce natural toxins in their leaf tissues, creating natural resistance to pests like the Colorado potato beetle. She works with Christina DiFonzo, professor in the Department of Entomology, to identify resistant potato plants in the field and assess how consuming different potato plants influences the life cycle of the Colorado potato beetle in the lab.

In addition, Kaiser collaborates with Robert Last, Barnett Rosenberg Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and uses the facilities at the MSU Mass Spectroscopy Core to examine the biochemical profile of resistant plants. She can then determine which leaf compounds are necessary for insect resistance.

She also partners with C. Robin Buell, University Distinguished Professor in the MSU Department of Plant Biology, to understand which genes are responsible for the production of these resistance compounds in wild potatoes. Kaiser identifies key DNA differences between potatoes that are resistant to the Colorado potato beetle and ones that are susceptible to the pest by comparing the biochemical profiles.

“I combine all this information to make cross pollinations between the wild and cultivated potatoes and select potato varieties with the unique combination of genes necessary for insect resistance,” Kaiser said.

She said the USDA NIFA Predoctoral Fellowship is an asset as she prepares to begin her career.

“This fellowship provides an unparalleled opportunity to expand the scope of my research and will robustly equip me to enter the workforce as a plant breeder,” she said.

Genevieve Hoopes

Hoopes, a Ph.D. candidate in the MSU Cell and Molecular Biology Program, focuses on explaining the role of the circadian clock on the potato tuber set, or the number of tubers each potato plant produces.

“The circadian clock is an internal biological mechanism that controls numerous processes related to environmental adaptation,” Hoopes said. “In humans, the circadian clock regulates sleep-wake cycles, while in plants, it regulates flowering time.”

Genes known to be controlled by the circadian clock in other crops are also involved in the number of tubers a potato plant produces; however, little is known about the circadian clock in potato and how it affects yield.

Hoopes and her collaborators crossed two potato varieties with different circadian traits in order to examine the role the circadian clock plays in potato plants. They then measured yield and the speed of the circadian clock in terms of how long it takes a potato plant to complete one leaf movement cycle. Plant leaves move in a rhythmic or cyclical manner controlled by the circadian clock.

While it’s still too early for provide any specific results, Hoopes is hopeful they will know more by the end of fall.

The USDA NIFA predoctoral fellowship will be helpful as this study moves forward, said Hoopes, who is advised by C. Robin Buell, Director of the MSU Plant Resilience Institute, and David Douches, director of the MSU Potato Breeding and Genetics Program.

“This fellowship will enable me to expand upon my work and use additional techniques to understand the role of the circadian clock in yield in potato,” she said. “Identifying the genes behind these traits could lead to better growing and higher yielding potatoes, providing an important source of food in the midst of changing climates and the increasing worldwide population.”

Print

Print Email

Email