VINES of change: 25 years of Michigan wine grape evolution

From experimentation to precision, how Michigan’s wine industry matured through varietal focus, science-driven viticulture and collaborative strategy.

Tradition as trajectory: Understanding the past to navigate the future

A retrospective analysis provides essential context for understanding the current state and future direction of any industry. As composer Gustav Mahler famously noted, “Tradition is not to preserve the ashes, but to pass on the flame.” In agriculture, and viticulture especially, this means that history is not merely a record of past practices, but a foundation for informed innovation. While modern technologies continue to offer powerful new tools for vineyard management, it is historical insight that reveals why certain approaches were adopted, how challenges were previously addressed, and what lessons have shaped today’s methods. Understanding this trajectory is crucial for guiding sustainable, strategic development, particularly in dynamic sectors like Michigan’s wine grape industry.

The purpose of this article is to reflect on the evolution of Michigan’s grape and wine industry over the past 25 years, a period marked by a deliberate shift from a largely experimental and uncertain winegrowing landscape to one producing site-expressive, cool-climate wines of growing national relevance. This transformation has not been accidental. It has been shaped by intentional cultivar selection, research-driven innovation in vineyard management, and the rise of a collaborative ethos, anchored in sustained dialogue between the Michigan State University Extension grape team and the state’s growers, winemakers and vineyard managers. Together, they have fostered a continuous cycle of experimentation, feedback and shared advancement.

Today, Michigan’s grape and wine industry stands at a pivotal crossroads. Scientific knowledge, though indispensable, is no longer sufficient on its own to address the complex pressures of climate change, land-use constraints, market saturation and economic volatility. Real progress now demands an infrastructure of shared learning, spaces where practitioners and policymakers can interrogate assumptions, align strategies and plan collectively, beyond the narrow metrics of competition or marketing.

The emergence of the Dirt to Glass™ Conference marks this strategic turn. More than an annual gathering, it represents a new kind of forum: one that connects Michigan’s industry with national and international expertise, elevates the conversation from products to systems, and signals a deeper shift. Michigan is no longer trying to prove it can grow grapes; it is now intentionally building the cultural, scientific and institutional capacity required to lead in the next era of cool-climate viticulture.

A quiet revolution in the north

For decades, Michigan’s wine industry struggled to define its identity. Overshadowed by the gravitational pull of California and often dismissed as unsuitable for Vitis vinifera cultivation, even by some early stakeholders and a few past Michigan State University (MSU) specialists, the state was frequently regarded as a viticultural periphery. The perception that “Michigan is better suited for juice than for wine” was not only common in the 1980s but also reflected in formal assessments during the Michigan Wine Competition, as documented in the archives of the Michigan Grape and Wine Industry Council. Critics questioned whether the region’s grapes could ever achieve the ripeness, phenolic structure and aromatic complexity required for high-quality wine production, suggesting that, at best, Michigan might have a future in hybrid grape cultivation but not in premium Vitis vinifera wines.

This skepticism reinforced the belief that Michigan’s future lay in Concord and Niagara juice grapes, not in cultivars like Riesling or Pinot Noir. This identity crisis was not only about climate, though climate was often used as an excuse. This was about viticultural mindset.

Many vineyard management practices (and vineyard managers) were directly adapted from juice grape production systems, without full consideration of the different physiological and quality demands of wine grapes, with the primary goal of maximizing yield rather than optimizing fruit quality. These included excessive nitrogen fertilization, extensive-excessive use of chemical weed control, low vine density with wide row spacing, pruning strategies based solely on node counts, high cordon training systems combined with split canopies and minimal canopy management, and overcropping. Although some of these methods were supported by earlier research trials from MSU, they ultimately proved incompatible with the physiological and qualitative needs of Vitis vinifera.

The result was often poor fruit composition, increased disease pressure and uneven ripening, highlighting the need for a transition toward quality-driven, precision viticulture management tailored to Michigan’s cool-climate conditions. Fruit quality suffered, and confidence in Michigan-grown wine grapes remained low throughout much of the early development period. The prevailing solutions at the time, and, regrettably, still today, relied heavily on increasing chemical inputs to manage fruit rot and disease pressure, even if leading viticultural regions around the world were moving in the opposite direction, embracing canopy-based prevention, site selection and proactive vineyard management over reactive chemical intervention.

The region’s challenging climate was routinely blamed as the core limitation, deflecting attention from more fundamental viticultural issues such as suboptimal site selection, inadequate canopy architecture, excessive nitrogen fertilization and outdated vineyard management practices. Rather than addressing the root causes of poor fruit quality, many approaches merely treated the symptoms chemically, delaying the industry's shift toward more sustainable, precision-driven strategies. It would take a new generation of growers, researchers and winemakers to slowly dismantle that paradigm and replace it with a more intentional, quality-focused approach. And that transformation now defines Michigan’s modern wine industry. In fact, over the past 25 years, that narrative has changed, not through a singular breakthrough, but through the gradual and methodical accumulation of scientific, practical and cultural advancements.

The transformation has been quiet yet deliberate, and today, it is undeniable. Much of this progress was catalyzed by a collaborative, self-reflective culture among Michigan winemakers. Through regular peer-to-peer wine tastings and constructive critique, a small but determined group steadily improved wine quality and concurrently advocated for more region-specific viticultural research at MSU. Their input directly influenced the academic agenda and helped align research priorities with grower and industry needs. At the heart of this evolution lies not only new techniques, but a philosophical shift, from maximizing volume to cultivating value, from expanding acreage to refining intentionality.

This transition can be understood through five interdependent pillars: varieties, innovation, nutrition, environment and strategy (VINES). These form the conceptual foundation of the VINES framework, not merely as an acronym, but as a reflection of a new ethos in Michigan viticulture. While no single figure alone shaped this transformation, it was spearheaded by a coalition of forward-thinking growers, winemakers, vineyard consultants, wine professionals and researchers. Their shared vision, combined with collaboration with MSU, produced not only improvements in vineyard and winery practices but also created a robust knowledge base, a living blueprint for the region’s continued growth and identity.

From possibility to precision: The strategic evolution of grape varieties in Michigan

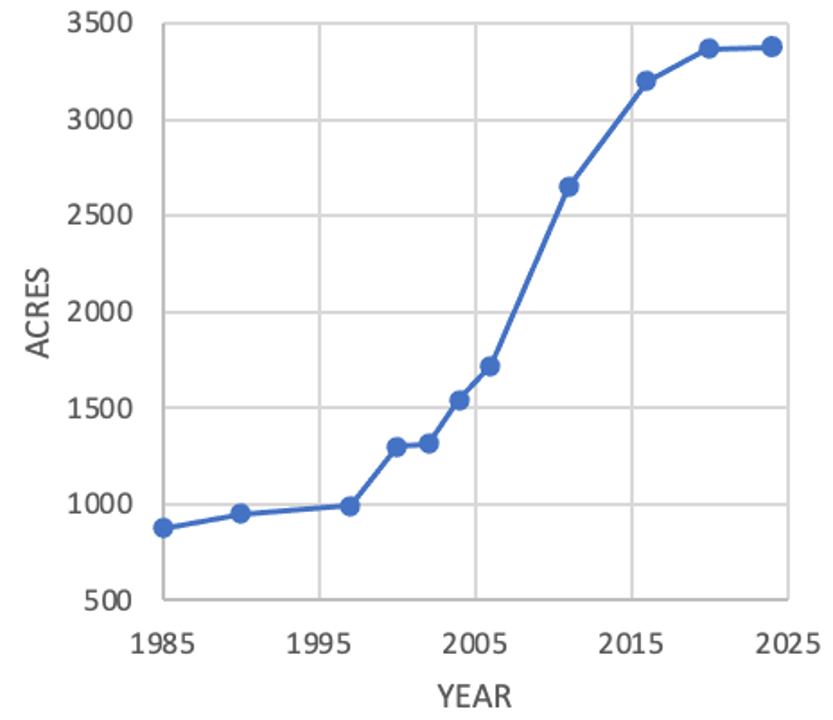

Michigan’s emergence as a cool-climate wine region did not begin with branding or marketing initiatives. Rather, its foundation was laid through strategic varietal selection, rooted in long-term regional adaptability and empirical learning. As an example, in 2004, a strategic plan with an ambitious goal was set and driven by the Michigan Grape and Wine Industry Council. They aimed to have 10,000 acres of wine grapes in Michigan by 2024. At that time, only 1,500 acres were dedicated to wine grape cultivation, and the target reflected a strategic vision for the future of Michigan’s wine industry. As of 2024, Michigan’s wine grape cultivation has grown to 3,375 acres, a significant increase over the years but still short of the original goal (Figure 1). A shortfall of 6,625 acres highlights the challenges faced by the industry in meeting its own growth targets.

At the 2025 Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo, Joe Herman, an important and revolutionary grape grower in Michigan, told us “the target of 10,000 acres was achieved, because we planted three times 3,000 acres.” What does this mean? In the early years of the industry, vineyard plantings across the state often resembled experiments in hopeful adaptation. A wide and sometimes eclectic array of cultivars was planted with the expectation, rather than the assurance, that some might thrive under Michigan’s unique climatic conditions. As one retired winemaker candidly reflected, “Back in the day, we planted just about everything, no idea what we were doing or why. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it was a disaster. At least we learned what not to grow and what the market didn’t like.”

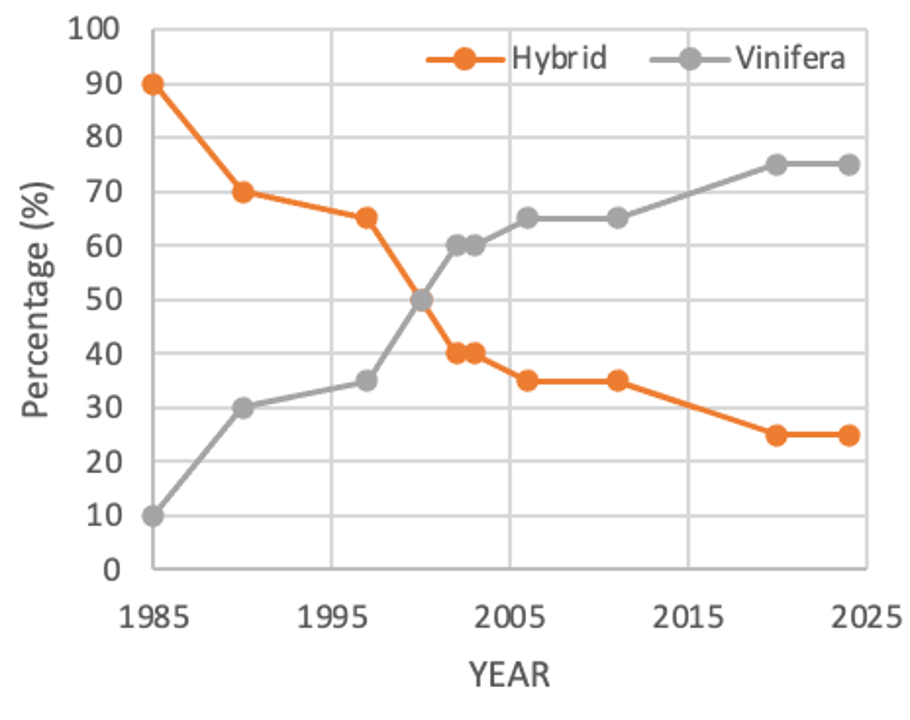

Today, by contrast, Michigan’s varietal landscape reflects a matured, data-informed and site-specific viticultural strategy, driven not only by climatic and agronomic considerations but also by market recognition, growing wine professional appreciation, and increased consumer demand. Five cultivars, Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Cabernet Franc, now comprise over 75% of total vineyard acreage statewide (Figure 2). This convergence is not merely a function of fashion or trend. Rather, it reflects decades of coordinated research, grower-led innovation and collaborative trials, some of them led by MSU in partnership with the state’s viticultural and enological community.

For example, more than two decades ago, MSU initiated formal variety trials in both northwest and southwest Michigan. These trials were supported by a coalition of forward-thinking growers and winemakers who sought empirical guidance on cultivar suitability. At the time, however, the initiative was not universally welcomed. Some stakeholders questioned its necessity, with one remarking, “Michigan already has a good set of cultivars, we don’t need a variety trial.”

In retrospect, the importance of this work has become clear. The diversity of winegrape cultivars planted in Michigan today is markedly different from what it was three decades ago. Several cultivars initially tested in MSU’s variety trials, such as Blaufränkisch, Teroldego and the cold-hardy hybrid Marquette, have since become pivotal in elevating Michigan’s wine quality and market identity, particularly in niche segments. These cultivars offer critical benefits such as winter hardiness, color and phenolic stability, and consistent ripening under cool-climate constraints, all key factors for both growers and winemakers. Among the core vinifera cultivars, Riesling for the northwest and Cabernet Franc for the southwest, have proven to be especially well-suited to Michigan’s variable climate. Their combination of cold tolerance, acid retention and aromatic potential, even in challenging growing seasons, allows them not only to survive, but to produce wines of exceptional quality and character.

These cultivars demonstrate a remarkable ability to express site specificity, the foundation of what is traditionally referred to as terroir in Old World viticulture, a concept that is becoming increasingly relevant and measurable within Michigan’s American Viticultural Areas (AVAs). This transition, from a landscape once defined by uncertain experimentation to one now shaped by strategic, site-specific focus, marks more than just a technical evolution. It reflects a fundamental philosophical shift within Michigan’s wine industry: a move from planting what is merely possible to cultivating what is regionally optimal, based on data, observation and intention.

As Dominique Lafon of Domaine des Comtes Lafon in Meursault famously stated, “You don’t make great wine in the cellar. You grow it in the vineyard. Everything else is just translation.” Lafon’s words, spoken from the heart of Burgundy, underscore a truth that now resonates across Michigan’s AVAs: vinification is not where greatness begins, it is where it is revealed. The core of wine quality lies in the vineyard, and that realization has reshaped how Michigan growers now approach variety selection, canopy management, and long-term vineyard management. Michigan is no longer merely producing grapes for winemaking, it is implementing practices that optimize fruit composition and consistently support the production of high-quality, site-expressive wines. The “translation” has begun.

Engineering ripeness: The role of canopy innovation in Michigan viticulture

While matching cultivar to site is foundational to regional success, it represents only the first step in optimizing wine grape production. What has truly distinguished Michigan’s viticultural progress over the past two decades is the MSU and industry’s innovative rethinking of vineyard management, particularly in terms of canopy architecture and phenological control. The Department of Horticulture at MSU has played a central role in this transformation, through pioneering collaborative research on techniques such as early leaf removal (ELR), early-season canopy hedging and crop control. These practices have reshaped how Michigan growers conceptualize and manage the key environmental factors of light penetration, air circulation and disease pressure.

In a seminal 2010 study in the northwest (Brys Estate Vineyard and Winery) and southwest (Lemon Creek Winery), the MSU research team demonstrated that the beneficial effects of ELR on phenolic development and disease resistance in Merlot, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc clusters were driven not only by changes in hormonal signaling but by an early season improvement in the fruit zone microclimate, previously assumed not important for fruit maturation. In fact, by selectively removing basal leaves during the pre-bloom or bloom stages, growers could increase sunlight exposure and airflow around clusters, resulting in better color development, improved tannin accumulation and reduced incidence of Botrytis and other fungal pathogens.

The implications of this finding were substantial. It suggested that vineyard architecture (not chemical input) is the most powerful tool at a grower’s disposal. In other words, even in a cool and frequently overcast climate such as Michigan’s, canopy structure can function as an effective instrument for advancing ripening, enhancing fruit quality and reducing fungicide dependency. This paradigm shift, from reactive disease management to proactive canopy engineering, has had lasting impact across Michigan’s AVAs.

Nutrition: From inputs to integrated resilience

While architectural precision in canopy management lays the structural foundation for vine health, it must be complemented by a robust, physiological approach to vine nutrition, one that moves beyond traditional fertilization and considers plant resilience under abiotic stress. In recent years, MSU, in collaboration with several southwest Michigan wineries such as 12 Corners Vineyards, has conducted applied field trials exploring the role of biostimulants. These compounds represent an emerging class of tools aimed at supporting vine performance under environmental stress conditions, such as heat waves and drought events. Experimental results have shown that these biostimulants can enhance stomatal conductance, improve vine water relations and mitigate physiological stress without compromising fruit composition or yield consistency.

In parallel, MSU researchers have investigated the role of fertirrigation in young vineyard establishment, particularly in the context of several recent years marked by vine decline, delayed maturity and variability in fruit quality at harvest. Trials revealed that targeted water-nutrient delivery, especially in the first five years of vineyard life, is a critical factor for successful canopy development and yield stabilization. When paired with micronutrient correction (e.g., boron, magnesium, zinc), irrigation has been shown to significantly enhance berry size, cluster uniformity and ripening, leading to improved fruit quality.

These studies reflect a broader conceptual shift: from viewing nutrition as a simple matter of inputs to understanding it as an integrated and dynamic component of vine stress physiology. In this context, water, nutrients and biological amendments are not isolated interventions, but part of a cohesive strategy for building vine resilience in Michigan’s variable climate. This evolution is also visible in ongoing research on soil health and cover cropping.

The MSU viticulture team, in partnership with several private stakeholders, is developing region-specific cover crop strategies tailored to Michigan vineyard soils, moving beyond generic seed mixes designed for other climates or cropping systems. This work aims to enhance soil structure, microbial biodiversity and nutrient cycling, while reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers and chemical weed control. These sustainable practices mark a significant transition away from input-driven agronomy and toward precision viticulture. Together, these innovations signal Michigan’s deepening commitment to intentional viticulture, not only above ground in canopy and cluster, but below ground in root, soil, microbiome and system resilience.

Environment: Resilience by design in a climate of uncertainty

In Michigan, where a single growing season can oscillate between midsummer drought and harvest-season rainfall, vine resilience is not a luxury, it is a viticultural necessity. It is precisely at this intersection of natural variability and agronomic necessity that Michigan’s winegrowing identity begins to assert itself on the global stage. The Great Lakes region offers a terroir that is both distinctive and dynamic. While the lakes moderate temperatures, extending the growing season and buffering against early autumn frosts, they also introduce significant climatic variability. Late spring freezes, abrupt temperature fluctuations, unpredictable rainfall events and compressed ripening windows are not anomalies, they are endemic features of Michigan’s climate.

The viticulture research team at MSU has consistently approached these challenges not as seasonal disruptions, but as permanent environmental constants requiring proactive system design. Their work emphasizes that resilient vineyard architecture, from cultivar selection to canopy timing, must be integrated from the outset, rather than applied as reactive solutions.

One illustrative example is MSU-led research involving cold-hardy hybrid cultivars, particularly Marquette. Commonly planted on marginal or frost-prone sites, these hybrids have demonstrated significant potential to reduce yield loss resulting from late spring frost. In such conditions where Vitis vinifera would be high-risk, hybrids offer a more reliable option for maintaining economic viability. Crucially, this research reframes frost risk not only as an external problem, but as a structural feature of Michigan viticulture, a variable to intelligently navigate through informed site selection, pruning strategies and crop load management.

This philosophy, one of integration rather than resistance, is emblematic of Michigan’s broader evolution as a cool-climate wine region. The state is no longer reacting to environmental constraints as if they were temporary challenges to be managed away. Instead, it is designing systems that work with those constraints, embracing variability as part of the region’s identity. Michigan is learning to optimize within its climatic realities, building a viticulture that is not only adapted but resilient by design. As Elena Walch, a pioneer of sustainable alpine viticulture in Alto Adige, has observed, “To respect nature is to make wine with precision. There is no tradition without adaptation.”

Walch’s philosophy echoes Michigan’s current trajectory, one that blends viticultural respect with technical innovation. Just as alpine regions must tailor their practices to dynamic terrain and climate, so too must Michigan continue to evolve, not by resisting its environment, but by making precision and adaptation the cornerstones of its winegrowing identity.

Strategy: From agronomy to system stewardship

Environmental intelligence in viticulture does not end at the vineyard’s edge. Increasingly, long-term success in Michigan winegrowing depends on strategic, system-level thinking, the ability to integrate climate adaptation, yield forecasting, labor planning and economic sustainability into vineyard and winery decision-making. MSU’s viticulture program has directly contributed to the development of predictive yield and site selection models, precise and timely vineyard tasks that help growers make real-time decisions based on crop potential and phenological stages. These tools signal a broader shift in the industry, from measuring success by yield alone to defining it through efficiency and fruit quality.

This transition marks a deliberate move away from viewing viticulture solely as an agronomic pursuit. Instead, winegrowing is now understood as a logistical and managerial discipline, where long-term planning, risk modeling and data-informed decisions are as essential as soil health or canopy design (Figure 3). Elio Altare once said, “We had to start over, not just in the vineyard, but in our minds. Understanding why we do something is more important than how.” This quote, born from Altare’s role in the Barolo revolution of the 1980s, reflects a moment when a new generation of growers challenged long-held traditions in favor of intentional, quality-focused viticulture and winemaking transforming Barolo into a world-class wine. This mindset, rooted in questioning inherited practices and refocusing on purpose, mirrors the intentionality now shaping Michigan’s varietal landscape.

As Michigan’s wine industry matures, its leadership must embrace integrated, forward-looking strategies, particularly as climate variability, labor shortages and land-use constraints become more acute. These challenges demand not only better tools but also a fundamental transformation in mindset. MSU’s research and outreach have not only equipped growers and winemakers with improved decision-making instruments, but they have also challenged them to redefine their roles.

The goal is no longer to simply maximize yield or minimize inputs, as once defined by a juice grape production model. Instead, the modern imperative is to act as stewards of a fragile but responsive ecosystem, balancing economic viability with ecological responsibility, and elevating both fruit and wine quality as outcomes of intentional, adaptive management from vineyard to cellar. This strategic lens positions Michigan not only as a regionally adaptive winegrowing state, but as an emerging model for cool-climate sustainability. It offers a clear and replicable example of how science, collaboration and intentionality can shape a resilient and quality-driven future for viticulture in the face of uncertainty.

From science to vision, building Michigan’s wine future

Science alone, while indispensable, is not sufficient. The complex challenges facing Michigan’s grape and wine industry today, market saturation, climate change, land-use pressure and economic uncertainty, will not be solved by research articles alone. These issues demand something more: community, dialogue and a shared strategic vision.

This is why the creation of the Dirt to Glass™ (DTG) conference marks a pivotal moment in Michigan’s wine culture. Far from being a symbolic or ceremonial event, DTG represents the emergence of a new cultural and intellectual infrastructure for the state’s grape and wine sector, a shift away from chasing medals at competitions toward building shared knowledge and fostering long-term interactions. The conference distinguishes itself by inviting national and international expert speakers with high-level insights, avoiding generic or too specific contents and ensuring that discussions remain deeply relevant to Michigan’s grape and wine realities.

DTG provides a space where growers, winemakers, researchers, wine professionals and policymakers can converge, not around medals or marketing, but around coherence, competence and collective learning. Launched by a motivated and forward-thinking group of stakeholders, DTG has become a forum for interrogating methods, challenging assumptions and planning the future of Michigan grape and wine industry. National and international speakers engage directly with Michigan’s grape and wine leaders in interactive, solution-driven sessions, elevating the discourse from branding to strategy, from products to systems.

The best wine regions in the world are not defined solely by latitude, elevation or soil, but by intentionality, the consistent, thoughtful alignment of practice with purpose. As Italian winemaking legend Angelo Gaja once said, “Making wine is not a job. It’s a way of life. You have to put your soul into every vine, every barrel, every bottle.” This ethos, central to Barbaresco and Barolo, resonates deeply with the direction Michigan is now taking. For the first time in its modern viticultural history, Michigan is operating with intention. It is planting what it knows, pruning with purpose, and farming for flavor. More importantly, it is developing the leadership capacity and institutional framework needed to sustain that growth across generations.

The role of Michigan State University in this transformation cannot be overstated. The impact of the university’s research in viticulture, entomology, pathology soil health and precision agriculture goes far beyond published papers or experimental trials. It’s true value lies in the conversations now unfolding across the state, catalyzed by the DTG conference. These are conversations about canopy structure and light interception, about hybrid resilience and site specificity, about managing vineyards not as static monocultures but as dynamic ecosystems that incorporate cover crops, water stewardship and digital technologies.

Michigan is no longer trying to prove it can grow grapes. That question has already been answered. The question now is far more compelling: Is Michigan ready to support research for cool-climate viticultural innovation? Hic Sunt Futura.

Print

Print Email

Email