What is the Kirtland’s Warbler? Part 1

Add Summary

Oct. 9, 2013

Jackie Hulina was a master's student in the Michigan State University's Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability.

So you're wondering what it takes to be a researcher? Be a book-worm.

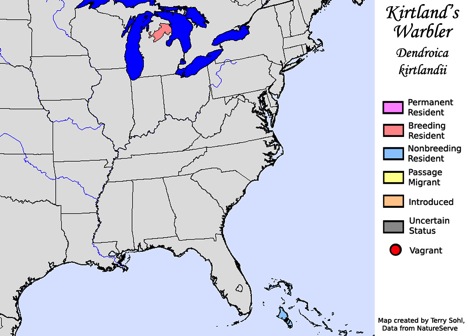

When my adviser first suggested that I look into Kirtland's warblers, I honestly had no idea what they

were. At least 88 references later (the number of articles currently saved in my Endnote account), I now know that Kirtland's warblers are an insectivorous songbird that migrates from the early successional jack pine forests of Michigan to the dense shrubby areas of the Bahamas archipelago.

In plain English, that means they eat bugs, prefer Christmas-tree sized jack pines in Michigan, and spend

their winters in the Caribbean.

So why are they called the firebird?

Kirtland’s warblers are very particular – they only live in early successional habitat, and those Christmas-tree sized jack pines need fire to regenerate. Without fire, the jack pines would just keep growing, leaving the firebird without a home. That’s exactly what happened after 1912 when Michigan began to suppress naturally occurring wildfires.

Building up to 1912, the timber industry had been clearing forests across the lower peninsula of Michigan, and agriculture took root in the open areas. Since they no longer had to worry about fire after the government became involved, people planted trees that were more profitable to the timber industry in Kirtland’s warbler habitat – aka very little jack pine habitat for the firebird. Agriculture was a double-edged sword, since it both reduced habitat and introduced a brood parasite called the brown-headed cowbird.

Brood parasites, like the brown-headed cowbird, are essentially lazy parents. They lay their eggs in other birds’ nests and never return, which is an adaptation attributed to cowbirds’ historical lifestyle following herds of buffalo.

If that isn’t bad enough, the baby cowbirds are like the bullies at daycare. Cowbirds are bigger than the host’s offspring, beg for food more often, and literally kick the host’s young out of the nest. Did I mention that their eggs are nearly identical to those of the Kirtland’s warbler?

If that isn’t bad enough, the baby cowbirds are like the bullies at daycare. Cowbirds are bigger than the host’s offspring, beg for food more often, and literally kick the host’s young out of the nest. Did I mention that their eggs are nearly identical to those of the Kirtland’s warbler?

With little habitat left and the threat of the brown-headed cowbird, Kirtland’s warblers were declining fast.

Stay tuned for Part 2, which will show you how KW went from a seemingly hopeless past to becoming one of the most revered endangered species recovery successes.

*Note: Map credit can be found here. The cowbird eggs are shown with chestnut-sided warbler eggs, © George H. Harrison

Print

Print Email

Email