Who am I and why am I at MSU?

Add Summary

Feb. 21, 2017

Ciara Hovis is working toward her PhD with Dr. Jack Liu studying the global soy trade using the telecoupling framework between the United States, Brazil and China.

A professor posed these two questions to my first year grad student cohort. And I realized I did not have a clear answer. If he asked me a year ago and replaced MSU with my undergrad alma mater, I would have fired off a response, no problem. I was a college student studying ecology and sustainability, with the goal of getting into graduate school to get a PhD. Since graduating this past spring, however, my mindset and situation has completely shifted.

Who am I? I’m Ciara Hovis, a first-year PhD student at Michigan State University studying global agricultural trade and the environment in China. That is my go-to response when asked to introduce myself lately. However, recently I have realized that response fails to convey key parts of me that shape the way I approach my studies and the world in general.

If you look at my parentage, it seems I was destined to become an ecologist. My mother spent the majority of her career teaching biology and environmental science, and my father is a wildlife biologist. Together, they instilled in me the values of environmental stewardship and education, which led to the highlights of my high school career being academic competitions in taxonomy (particular bird taxonomy) and ecology. Around the age of 13, I decided it was my destiny to get a PhD in ecology, and I worked tirelessly from then on to ensure that would happen.

If you look at my parentage, it seems I was destined to become an ecologist. My mother spent the majority of her career teaching biology and environmental science, and my father is a wildlife biologist. Together, they instilled in me the values of environmental stewardship and education, which led to the highlights of my high school career being academic competitions in taxonomy (particular bird taxonomy) and ecology. Around the age of 13, I decided it was my destiny to get a PhD in ecology, and I worked tirelessly from then on to ensure that would happen.

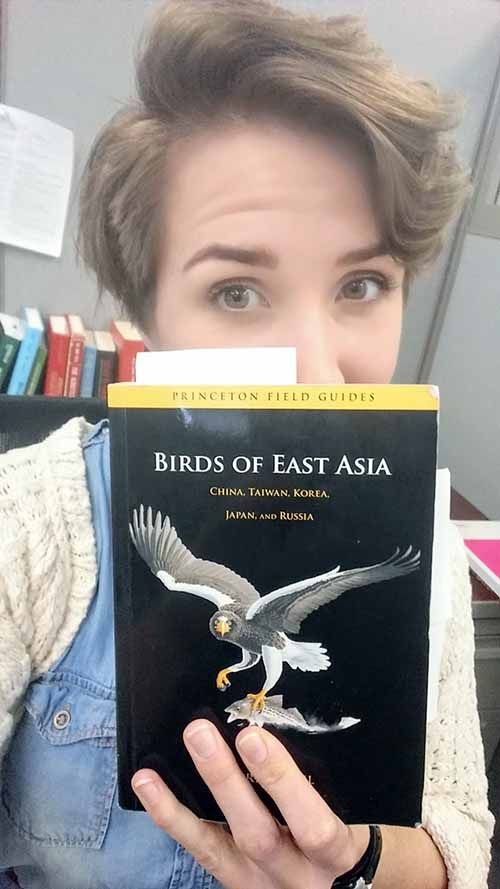

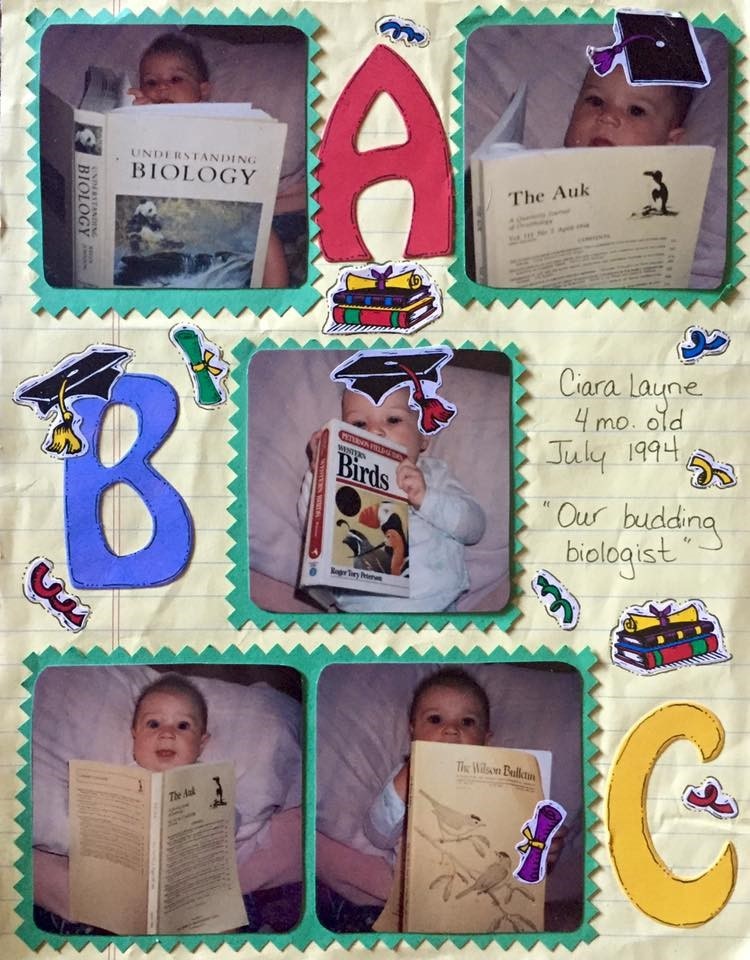

Proof of my early indoctrination by my parents. I will never know if my decision to get a PhD in ecology was of my own making or something that was seeded in my brain before I could talk.

Why am I at MSU? Fast-forward to my last semester of undergrad. I accepted a PhD position at Michigan State doing research focused on China, and four days after graduating I got on a plane to a country whose language and culture was a mystery to me. It took a few days for the reality of what I had done to settle in, and I contemplated buying a ticket home on more than one occasion. I was slowly realizing how hard research is. The difficulties that come along with field research, let alone internationally, are hard to comprehend until you experience them for yourself. Nevertheless, I persevered and took solace in doing what I do best: being obsessed with birds.

Though spotting wildlife in northeast China is rare, I stubbornly carried my bird guide everywhere. I didn’t use it as much as I would have liked, but I did get a glimpse of a Common Hoopoe (probably my favorite bird sighting to date) on my last day of fieldwork. I like to think that this was my reward for sticking it out for as long as I did. I ended up leaving with more questions than answers, but gained a new-found appreciation for the difficult process that is earning a PhD.

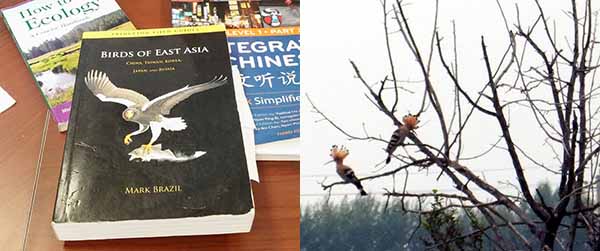

Left: My beloved bird guide gifted to me by my father who refused to let me go without one. My favorite pastime was flipping through the pages and pouring over the illustrations in the hopes I might get to see the real things. Right: The Common Hoopoes (Upupa epops) I ran through a cornfield at top speed to catch a glimpse of these birds.

Researchers and those with PhDs are not superhumans. We get sick, we miss home, and we make mistakes. There is a reason it an average of five years to get their PhD. It is HARD. My upbringing made me feel like I was born to get a PhD, and frankly this past summer was the r

Print

Print Email

Email