Field Horsetail: A Plant As Old As Time

February 2, 2024 - Johanna Flies and Erin Hill

Field Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) is part of one of the most primitive living plant families in the world. Dating back to the Carboniferous Period (354–290 million years ago), the ancestors of horsetail were tree sized and dominated the landscape, ultimately transforming into coal deposits found today (Dickinson & Royer, 2014; Hartzler, n.d.). A perennial relative of ferns, Equisetum is the only living genus in the Equisetaceae family. It has many common names including scouring rush, horsetail fern, meadow-pine, pine-grass, foxtail-rush, bottle-brush, horsepipes, snake-grass, and cornfield horsetail, (Neal et al., 2023; Washington State University, n.d.).

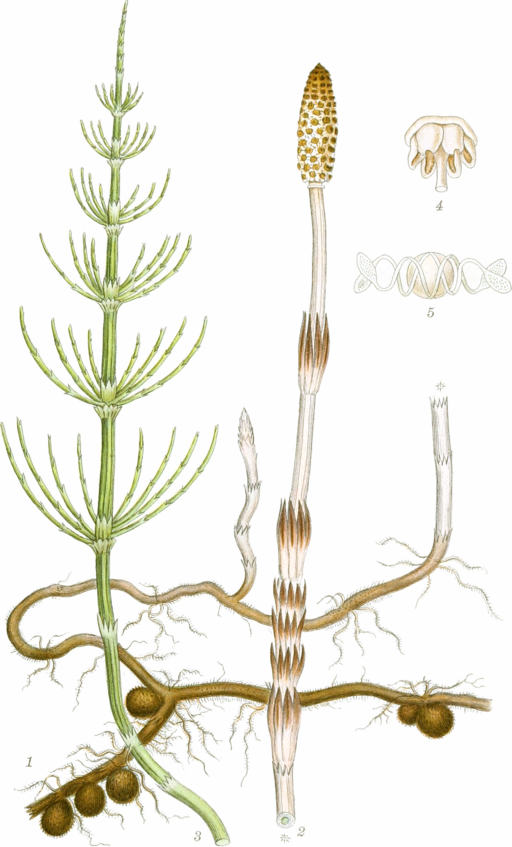

Field horsetail has two kinds of stems, the first of which emerges in the spring. It is light brown, leafless, and unbranched with spore-bearing cones developing at the tip (Sudan, n.d.). This stem, which grows to about 12 inches, is reproductive but not photosynthetic (Washington State University, n.d.). (See figures 1 and 2.)

After releasing their spores, these first stems begin to die back and the second, nonreproductive stems emerge. These stems, which look like small conifers or bottle brushes, are vegetative and photosynthetic, typically growing up to 2 feet tall (Washington State University, n.d.). (See Figure 3.)

The horsetail’s spores have curling, spring-like appendages that uncoil as the spores dry, helping to propel them into the air as well as burrow into the ground (Burrill & Parker, 1994; North Carolina State Extension, n.d.). Wet soil is needed for spores to germinate. Other site conditions that encourage establishment are full to partial sun and sandy or gravelly soil ranging in acidity from a pH of 4.0 to 7.0 (North Carolina State Extension, n.d.; United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service [USDA, NRCS], n.d.-a). Once established, horsetail’s primary mode of reproduction is vegetative, through its horizontal rhizomes and small tubers, which allow it to propagate even in drier and less optimal areas at a rate of up to 20 inches per growing season (Burrill & Parker, 1994; Hartzler, n.d.). This root system, described as “creeping,” “deep penetrating,” and “extensive,” can be found at depths of 6 to 10 feet. The roots give horsetail a “remarkable regenerative capacity” from the carbohydrate energy stored within (Washington State University, n.d.). (See figures 4 and 5.)

Field horsetail shares its genus with nine other species found in Michigan, among them Equisetum hyemale (scouringrush horsetail), Equisetum fluviatile (water horsetail), and Equisetum telmateia (giant horsetail) (USDA, NCRS, n.d.-b). Although all species found in the United States are potentially toxic to livestock, particularly horses, field horsetail has been used throughout the ages by humans in a variety of capacities including in herbal medicines, as a vegetable, and for veterinary uses (Burrill & Parker, 1994; Mount Sinai, n.d.; North Carolina State Extension, n.d.). The toxicity is due to thiaminase, an enzyme that inactivates vitamin B (CABI, 2021). The high silica content of the stems makes horsetail useful for cleaning because of its abrasiveness (Hartzler n.d.). Horticulturally, horsetail is used to make a fungicide for powdery mildew and blights (North Carolina State Extension, n.d.). Some of the Equisetum species, such as Equisetum hyemale, are marketed to gardeners for their ornamental qualities and adaptability to aquatic gardens, but those recommendations come with the caveat that once established, horsetail species can be difficult to remove and might be better suited for container plantings (Gardenia, n.d.).

Although horsetail’s remarkable ability to extend its territory via rhizomes and the resulting difficulty in eradicating it might be undesirable in certain environments, those same characteristics are a benefit in more fragile ecosystems such as riparian zones and wetlands (Husby, 2013). The deep roots of horsetail act as nutrient pumps in wetlands, transporting phosphorus, potassium, and calcium to the soil’s surface where other plants can then access them, boosting the overall vitality of the ecosystem (Husby, 2013). (See Figure 6.) Horsetail’s adaptability to low-nutrient environments as well as its tolerance of salinity mean it can handle the “stressful soil” of sand dunes whether near fresh or saltwater (Husby, 2013; Smith, 2023). In Michigan, varieties of horsetail can be found around both inland lakes and the Great Lakes shorelines (Reznicek et al., 2011). In Pennsylvania, horsetail has been found to be one of the first species to colonize and stabilize bluffs around Lake Erie (McPherson & Zimmerman, 2022). (See Figure 7.)

Cultural control methods

Controlling horsetail can be challenging and would likely require multiple tactics. Cultural control methods include use of heavy-duty landscape fabric to block stem growth, but rhizomes can often grow out to the edge of the fabric or find their way through any holes in the fabric (Burrill & Parker, 1994). Mulches have not been found to be very effective (Whatcom County Noxious Weed Board, n.d.). Horsetail can potentially be shaded out by using a nitrogen-focused fertility plan to favor more competitive plants as it does not readily respond to nitrogen (Washington State University, n.d.). Use caution when fertilizing near wet habitats, however, because of the risk of runoff and the potential for resulting eutrophication and dead zones in waterways (United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2023).

Small infestations may be successfully controlled via soil removal, though this can be an arduous process. The area needs to be excavated to a depth of 6 feet or more. The hole that remains needs to be lined (bottom and sides) with a tightly woven or nonwoven geotextile fabric, which prevents the reintroduction of rhizomes to the area. After the fabric is in place, the area can be backfilled with new soil from a noninfested area. Disposal of the infested soil needs to be considered. Placement elsewhere on the site will result in the introduction of field horsetail. )

Altering moisture availability by improving surface and subsurface drainage can also negatively influence horsetail. Be aware, however, that if this plant is found in a neighboring area where it is not controlled or eventually removed, reintroduction can be expected.

Mechanical or physical control methods

Mechanical or physical control methods for smaller areas of horsetail focus on trying to deplete the energy reserves of the rhizomes by removing the stems every 2 weeks during the growing season. This process can take 3 to 4 years to achieve success (Long, 2022; Burrill & Parker, 1994). Larger areas such as crop fields can be harder to control and use of tillage equipment can actually spread the plant due to its ability to regenerate through pieces of rhizome (Cloutier & Watson, 1985). Repeated mowing or tilling could be successful if timed to target regrowth before it has had the chance to replenish energy reserves in the roots, or before it reaches 8 to 10 inches (Cloutier & Watson, 1985). Such a strategy might require multiple years of effort.

Chemical control

Chemical control with herbicides is problematic because of the biology of the plant. The high silica content of the stems and the waxy coating on the plant limit herbicide absorption while the extensive root system often results in regrowth. Field horsetail is tolerant to most herbicides used in the landscape (Hill, 2019).

Gardeners and some agricultural applicators have had some success at growth suppression with repeated applications of glyphosate. Glyphosate is a broad-spectrum herbicide and will injure any desirable plants it contacts as a spray or drifted spray (Hill, 2019).

Glyphosate adsorbs strongly to soil in most cases (that is, clay and organic matter), allowing even sensitive crops to be planted shortly after application, meaning no carryover issues are expected. Glyphosate alone can take up to 14 days to show full activity under ideal growing conditions. Retreatment of the area may be required, depending on the degree of infestation. Glyphosate is most effective for perennial control in the late summer to early fall when plants will translocate the most to their root system, but it can be applied anytime the plants are actively growing (temperatures consistently above 50°F). Finally, be sure that the product has only the active ingredient glyphosate or glyphosate + pelargonic acid. Products with additional active ingredients may have other unwanted effects and may delay the planting of other plants in the coming season(s) (Hill, 2020).

Other herbicide options for suppression have site specific applications, may not be readily available, and should be considered only in consultation with an experienced party. (See figures 8 and 9.)

Additional care must be taken with applications near or in waterways. If there is visible water located near the site at the time of application or it is along the shoreline of the Great Lakes or Lake St. Clair, a permit is required prior to making an herbicide application; contact the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) Aquatic Nuisance Control Program Staff at 517-284-5593 for more information. Also, a list of approved aquatic herbicides needs to be consulted on the Michigan EGLE website (https://www.michigan.gov/documents/deq/wrd-anc-approvedherbicides_445623_7.pdf). Ingredients in nonaquatic products may be toxic to fish and other aquatic organisms (Whatcom County Noxious Weed Board, n.d.).

Biological control

No biological control is currently available.

References

Burrill, L.C., & Parker, R. (1994). Field horsetail and related species: Equisetaceae (PNW 105) Pacific Northwest Extension. https://www.maine.gov/dacf/php/gotpests/weeds/factsheets/horsetail-nw.pdf

CABI. (2021). Equisetum arvense (field horsetail). CABI Compendium. CABI Digital Library. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/10.1079/cabicompendium.21621

Cloutier, D., & Watson, A. K. (1985, May). Growth and regeneration of field horsetail (Equisetum arvense). Weed Science, 33(3), 1985, pp. 358–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4044272

Dickinson, R., & Royer, F. (2014). Weeds of North America. The University of Chicago Press.

Gardenia. (n.d.). Equisetum hyemale (horsetail). https://www.gardenia.net/plant/equisetum-hyemale

Hartzler, B. (n.d.) Equisetum: Biology and management. Iowa State Weed Science Online. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/encyclopedia/equisetum-biology-and-management

Hill, E. (2019, November 12). Weed removal #605875 [Expert response]. Ask Extension. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. https://ask2.extension.org/kb/faq.php?id=605875

Hill, E. (2020, June 25). Trumpet vine #655440 [Expert response]. Ask Extension. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. https://ask2.extension.org/kb/faq.php?id=655440

Husby, C. (2013, January 15). Biology and functional ecology of Equisetum with emphasis on the giant horsetails. The Botanical Review, 79, 147–177 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-012-9113-4

Long, J. (2022, April 4). April 2022 plant profile: Field horsetail: Weed or wonder? University of Washington. https://botanicgardens.uw.edu/about/blog/2022/04/04/april-2022-plant-profile-field-horsetail-weed-or-wonder/

McPherson, J., & Zimmerman, E. (2022). Great Lakes bluff seep. Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. https://www.naturalheritage.state.pa.us/community.aspx?=16040

Mount Sinai. (n.d.). Horsetail. Mount Sinai School of Medicine. https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/herb/horsetail#

Neal, J. C., Uva, R. H., DiTomaso, J. M., & DiTommaso, A. (2023). Weeds of the Northeast (2nd ed.). Cornell University Press.

North Carolina State Extension. (n.d.). Equisetum arvense. North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/equisetum-arvense/#.

Reznicek, A. A., Voss, E. G., & Walters, B. S. (2011, February). Equisetum variegatum. Michigan Flora Online. University of Michigan Herbarium. https://michiganflora.net/record/1206

Smith, P. H. (2023). Distribution and ecology of Equisetum variegatum (variegated horsetail) (Equisetaceae) on the Sefton Coast sand-dunes, north Merseyside, UK. British & Irish Botany, 5(2):114–130. https://britishandirishbotany.org/index.php/bib/article/view/147/183

Sudan, R. (n.d). Plant of the week: Common horsetail (Equisetum arvense). United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/equisetum_arvense.shtml

United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. (n.d.-a). Equisetum arvense L.: Field horsetail. https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=EQAR

United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. (n.d.-b). Plants database. https://plants.usda.gov/

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Sources and solutions: Agriculture. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/sources-and-solutions-agriculture#.

Washington State University. (n.d.). Wheat and small grains: Field horsetail. https://smallgrains.wsu.edu/weed-resources/common-weed-list/horsetail/

Whatcom County Noxious Weed Board. (n.d.). Control options for field horsetail. Whatcom County, Washington. https://www.whatcomcounty.us/DocumentCenter/View/27069/Horsetail-Management

Print

Print Email

Email