Impacts of high temperatures, heat stress and heat-related diseases in pigs raised indoors

As temperatures rise, the incidence of disease and heat stress also increases for pigs that are raised indoors.

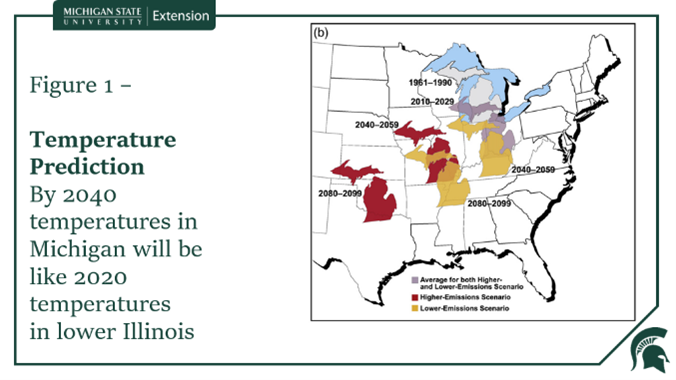

Pork producers in Michigan and elsewhere have faced numerous challenges due to the increasingly hot weather over the past 50 years. Long-term weather forecasts for the Midwest U.S. and Michigan indicate that periods of sustained higher temperatures will occur more frequently and for more extended periods (Figure 1). It is predicted that Michigan will continue to experience higher numbers of storms.

For both humans and our livestock, high sustained temperatures, especially when combined with high humidity, can cause heat stress and the subsequent effects to reduce health. All mammals are at risk of heat stress when temperatures reach a certain threshold. Pigs are more heat-stress sensitive at lower temperatures, about 77 degrees Fahrenheit. In comparison, humans have a temperature threshold for heat stress at about 82 F.

Heat stress and pigs

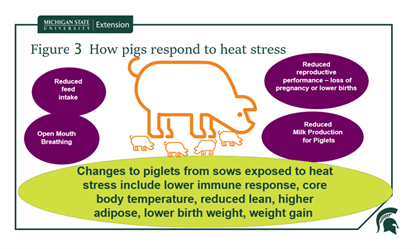

Pigs are most comfortable and productive when environmental temperatures are within their thermal comfort range, the thermal neutral zone, which varies by age, size, moisture and wind speed. The impacts of heat stress on pig health and performance become greater as animals grow larger. Pigs have a lower threshold than other mammals because they lack sweat glands, which are required for evaporative cooling and their lungs are relatively small compared to their body size, limiting the effectiveness of panting in reducing body heat. Effects of higher temperatures and heat stress on sows, boars and finishing pigs, for example, begin to appear at about 70 F and become more serious with higher temperatures or humidity.

For these reasons, it is important that all pig farmers and their staff can recognize the signs of heat stress or improve the pigs' ability to dissipate heat during the summer months. Primarily, pigs will pant to remove excess heat and exhibit behaviors such as lying apart from other pigs and changing their dunging patterns to create a wallow for cooling. Be prepared to take additional adaptive actions that extend beyond barn ventilation and other structural features.

Expected consequences of heat stress in pigs include decreased feed intake and performance in sows and piglets, as well as slower growth and reduced feed intake in grower pigs. Recent research has shown that heat stress also affects growth rate and immune response in piglets born to heat-stressed sows, causing a loss of gut barrier function. This barrier is a crucial part of innate immunity, helping to reduce infections from bacteria, viruses, parasites and mycotoxins.

Heat stress and diseases in pigs

Environmental factors, especially when combined with increased rainfall and severity, facilitate the survival and proliferation of certain insects, parasitic worms and other pathogens such as PEDV, PRRS, Salmonella and E. coli. Additionally, it is anticipated that warmer, wetter conditions will boost the levels of some mycotoxins contaminating corn, soy and other feed ingredients.

Adaptive measures to minimize impacts of higher temperatures and heat stress

Pig vulnerability to heat stress depends on numerous factors, including type of production system (e.g., indoor vs. outdoor operation), ventilation or other cooling equipment, pig genetics, nutritional status, life stage/size and stocking density. Changes in farm husbandry practices likely to bring the greatest impact per dollar will depend on disease or pathogen exposure (type and intensity), which may be highly farm-specific. Potentially useful adaptive measures are described briefly below:

- Minimize the direct effects of heat stress by reducing pig exposure to sustained temperatures that exceed the thermal neutral zone and cause reduced feeding and damage to the gut's barrier function. Make this a key part of every farm’s health plan.

- Increase ventilation rate in the barn.

- Provide shade on the air inlet side of the barn

- Maintain fans to maximize ventilation.

- Ensure that wall and roof insulation is intact to reduce heat and solar penetration into the building.

- Use roof materials with higher reflectivity to lower barn temperatures caused by solar gain.

- Combine fans, misters and sprinklers for evaporative cooling to decrease body temperature effectively.

- Reduce stocking density to help pigs separate from the heat produced by other pigs and improve airflow over the pigs.

- Provide ample access to fresh water.

Adaptive measures to minimize risks associated with indirect effects of heat stress include updating farm vaccination plans and implementing stricter biosecurity measures, manure management protocols and expanded or more strategic use of insecticides. It might also include more frequent testing for key mycotoxins that have been detected in your region (or in the area where your farm’s feedstuffs are grown).

- Your farm veterinarian is the best source of timely information on diseases emerging in your area, but neighboring farms and feed suppliers can often supplement those reports. Surveillance testing options for many key diseases that infect pigs now include assays for oral fluids, which can be easily collected from several animals simultaneously and are relatively inexpensive.

- Implement or strengthen biosecurity measures designed to better prevent key pathogens from entering your farm from outside. This includes such measures as rotating in a disinfectant shown to be highly effective against emerging pathogens or introducing a new barn insecticide effective against species that carry them. Since many pathogens enter through wildlife, particularly rodents and birds, taking measures to minimize their entry into barns, pens, or feedstuffs could provide a form of low-cost insurance.

- Work with a farm manure/environment specialist to develop a management strategy that minimizes risks associated with pond, lagoon and pit spillovers during heavy rain and flooding or other conditions leading to re-entry of manure into your barn. Swine raised outdoors and with access to deep mud and manure are also exposed to more diseases.

- Since manure is a critical factor determining levels of soil contamination with parasitic worm eggs, some of which can survive and remain infective in soil for >10 years, it is important for farms raising pigs outdoors to scrape and remove heavy deposits of manure, rotate pastures and to treat pigs for roundworms routinely as recommended by a veterinarian.

- Consider use of feed supplements (pro/prebiotics, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids) to help preserve gut health when challenged by exposure to important pathogens. Fiber can increase heat produced during feeding and amplify the effects of high temperature on pig performance. Consult your veterinarian or farm nutritionist to determine if a feed strategy that includes reduced fiber or feed supplements is right for your operation.

High temperatures and accompanying heat stress are important factors limiting pork production; both are projected to increase in importance as temperatures rise in most pork-producing regions of the U.S., including Michigan. In addition to direct adverse effects on pig health and performance, high temperatures can lead to increased exposure and susceptibility of pigs to infectious diseases and harmful mycotoxins. Fortunately, these effects can be minimized by low-cost adaptive measures that pork producers can implement as part of their herd health plans.

Print

Print Email

Email