Is it chestnut season in MIchigan? Or trouble with tribbles*

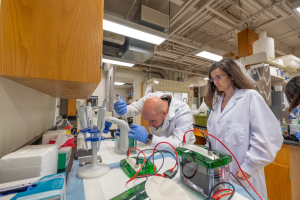

Post-doc researcher Giorgia Bastianelli continues long tradition of chestnut research at MSU

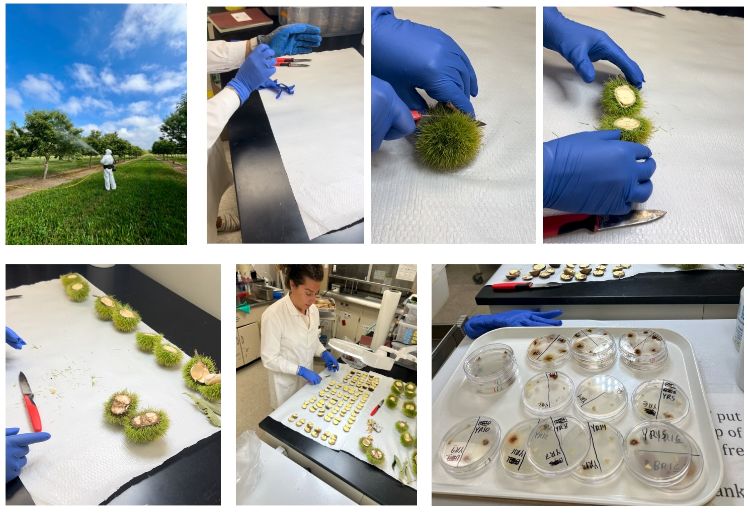

It’s harvest time and a busy season here in PSM as research resumes on the many trials tested in the fields. In the Small Fruit and Hops Pathology lab, postdoc researcher Giorgia Bastianelli tears into a batch of fresh chestnut burrs, beautiful to look at but dangerous to touch. Donning double gloves she carefully cuts them open to reveal the creamy white sponginess packed with protein and other nutrients, as well as some much less desirable brown bits: some of the results of work that began decades ago.

Chestnut trees once dominated eastern deciduous forests in and around the Appalachian mountains from Georgia to Maine, and contributed significantly to the economy and ecosystem. This free and readily available forest product fueled entire industries from building materials to food supplies, for humans and many other forms of flora and fauna. Then tragedy struck and within a few decades chestnut blight fungus changed America’s eastern deciduous forests seemingly forever.

However- that's just the beginning of the story for MSU because, by luck or by factor of evolution, Michigan is home to several stands of American chestnut trees that survive due to a naturally occurring hypovirulence in which the aggressiveness of the fungal pathogen is reduced by a hypovirus that resides in the cytoplasm of the fungus.

With this knowledge, and strong support from regional chestnut growers, Dennis Fulbright (who died in 2019) pioneered research here at MSU using these trees to creating productive cultivars with some resistance to the blight, identifying cultivars suited to Michigan production, developing a biocontrol for chestnut blight, then discovering a pollen incompatibility between chestnut species that threatened the nascent Michigan industry, and finally providing a legacy for research and producers, here and abroad.

Giorgia Bastianelli is a post doc research associate currently working with Timothy Miles, continues the tradition of working with producers to test cultivars, product applications, and provide results. Originally from Italy, where she worked with the largest chestnut processing facility in the world, this is Giorgia’s second chestnut harvest season at MSU.

Now she is testing samples sent from growers she works with for Internal Kernel Breakdown and for chestnut brown rot by Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi which was first reported in Michigan in 2017 Read more here. Giorgia's current work is funded by grants from Project GREEEN and Specialty Crop Block grants through the Midwest Nut Producers Council.

Cutting them open Giorgia finds that a significant portion of them have a brown section that contrasts to the creamy white healthy nuts. “Dennis started to see this when he was working with cultivars crossed with Asian trees. He called it “Internal Kernel Breakdown” and it is attributed it to incompatible genetics and it renders the nut useless to the grower,” Giorgia said.

While the fungus that blights chestnuts in the U.S. is starting to appear in European forests, “We only see IKB in the US where we must use other trees to pollinate the crop.” In their natural hardwood forest habitat, which still exists in Asia and Europe, chestnuts are responsible for their own fertility treatments. And they seem to do so with great success, as the chestnut industry continues to thrive, while it’s no longer a familiar food to modern Americans.

Will it be that way once again in eastern forests? “We are working toward that goal,” Giorgia says.

Top Left: Dennis Fulbright in the field, Lower left: Mario Mandujano, PSM research assistant III and Andrea Vannini meet in Italy, and Giorgia Bastinelli in the lab here in PSM.

Print

Print Email

Email