Managing hop powdery mildew in Michigan in 2020

Fungicides applied for powdery mildew can help growers avoid a number of damaging cone diseases.

Powdery mildew of hop (caused by the fungus Podosphaera macularis) is an emerging disease in Michigan that has serious implications for growers. Powdery mildew was confirmed in Michigan in 2014 and has been a concern on greenhouse/nursery plants for years. While it is the most serious disease in the Pacific Northwest, it was rarely an issue in the field in Michigan until 2017, when mild spring conditions and likely introduction of the pathogen from greenhouse plants resulted in significant powdery mildew disease on mature plants in hopyards without a history of disease. Seasonal disease severity is dependent on cultivar, environmental conditions and management programs. Focus on proactive management strategies, including sourcing clean planting stock, scouting regularly and utilizing a preventative fungicide management program.

Use clean planting material when establishing new hop yards since many insect and disease pests are readily spread via nursery stock. Consider purchasing a few plants from prospective nurseries and have them tested for diseases including mildews and viruses before committing to a large numbers of plants. Michigan State University Diagnostic Services can identify mildew microscopically and has experience working with hop plants (see information below for submitting samples to the clinic). Additionally, any other signs of poor handling at the propagator level may be used as an indicator of plant quality. Other signs of poor handling would include mite or aphid infestations, spray damage, nutritional issues or poor root development.

Symptoms

Powdery mildew resulting from bud infection appears in the spring white stunted shoots called “flag shoots.” Flag shoots are rare, accounting for less than 1 percent of all shoots in a field and making detection at this stage very difficult. Secondary lesions become visible as leaf tissue expands and first appear as raised blisters, which quickly develop into white, round colonies. Infected burrs and cones can also support white fungal colonies or may exhibit a reddish discoloration if infected later in development.

Burrs and young cones are very susceptible to infection, which can lead to cone distortion, substantial yield reduction, diminished alpha-acids content, color defects, premature ripening, off-aromas and complete crop loss. Cones become somewhat less susceptible to powdery mildew with maturity, although they never become fully immune to the disease. Infection during the later stages of cone development can lead to browning and hastened maturity. Alpha-acids typically are not influenced greatly by late-season infections, but yield can be reduced by 20 percent or more due to shattering of overly dry cones during harvest resulting from accelerated maturity.

Late-season powdery mildew can be easily confused with other diseases such as Alternaria cone disorder, gray mold, other cone diseases or spider mite damage. Several weak pathogens and secondary organisms can be found on cones infected by powdery mildew; limiting powdery mildew can reduce these secondary infections.

Scouting for powdery mildew involves monitoring the crop for signs and symptoms of disease and evaluating the efficacy of the control program being utilized. Keep records of your scouting, including maps of fields, a record of sampling and disease pressure, as well as the control measures utilized. Section your farm off into manageable portions based on location, size and variety and scout these areas separately. It is more practical to deal with blocks that are of the same variety, age and spacing. Walk diagonally across the yard and along an edge row to ensure you view plants from both the edge and inner portion of the block. Change the path you walk each time you scout to inspect new areas. Reexamine hotspots where you have historically encountered high mildew pressure. Due to increased humidity, hotspots may occur more often near tree lines or in low-lying wet areas of the yard. Scout as soon as plant or pests become active and continue until the crop or pest is dormant. Weekly scouting is recommended at a minimum.

If you are unsure of what is causing symptoms in the field, you can submit a sample to MSU Diagnostics Services. Visit the webpage for specific information about how to collect, package, ship and image plant samples for diagnosis. If you have any doubt about what or how to collect a good sample, please contact the lab at 517-432-0988 or pestid@msu.edu.

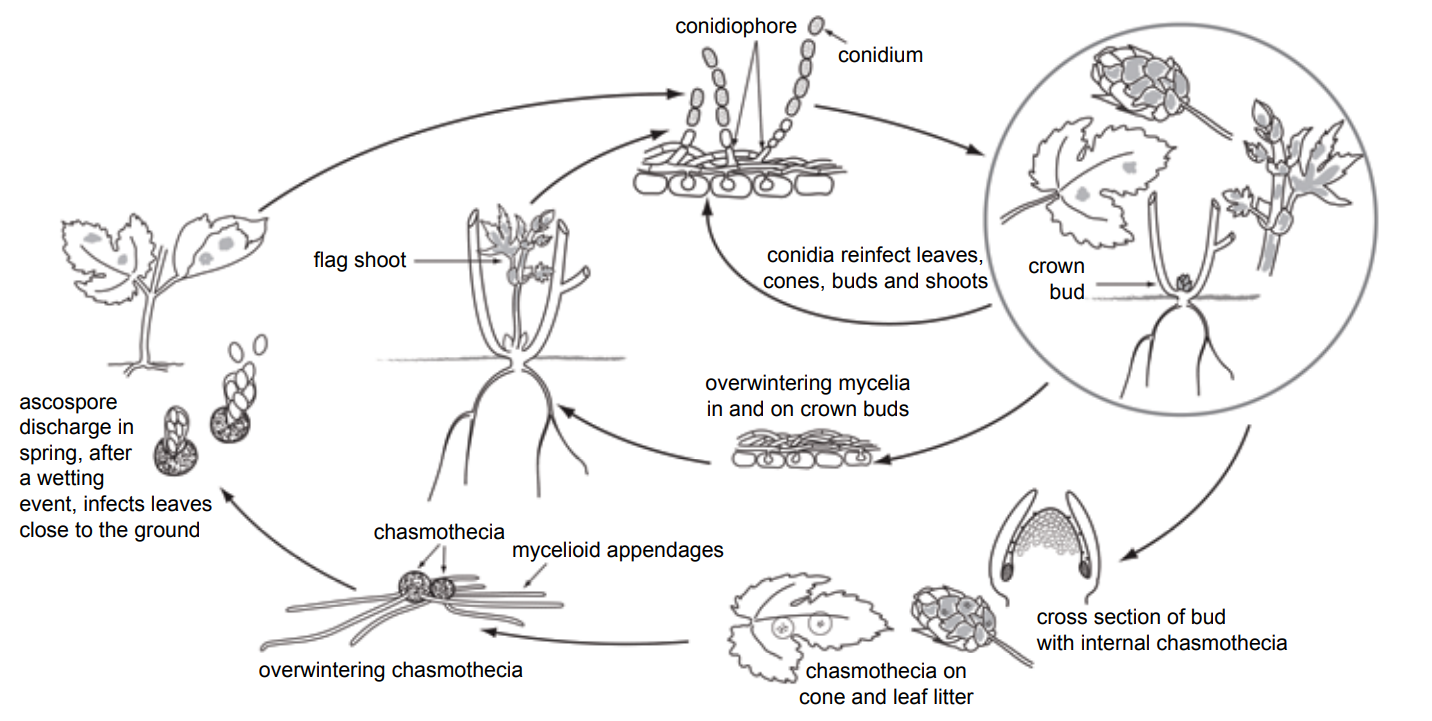

Disease cycle

Powdery mildew overwinters as fungal threads inside buds or potentially as resting spores in plant debris infected during the previous season. Symptomatic flag shoots emerging from infected buds can be covered with conidial spore masses, appearing white, stunted and with distorted leaves. Flag shoots are rare (less than 1 percent) and healthy shoots quickly outgrow infected shoots, making them tough to scout for. The spore masses on flag shoots spread to adjacent healthy tissue, causing new infections.

Sexual resting spores (ascospores) may also be present in spring on plant debris from the previous season. Ascospores are discharged and land on newly emerged shoots or leaves where they germinate, infect and eventually produce a new spore mass of asexual spores (conidia). Conidia arising from secondary infection are produced in large numbers over multiple cycles within the season as long as conditions are favorable and are dispersed via wind, rain splash, insects, tractors, equipment, and humans.

Conditions that favor powdery mildew are reported to include low light levels resulting from cloud cover, canopy density, excessive fertility and high soil moisture. Leaf wetness from dew or rain does not directly impact powdery mildew infection, but results from high humidity and cloud cover, which favors disease. Temperatures from 46 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit allow powdery mildew to develop, but disease is favored by temperatures of 64 to 70 F; disease risk decreases when temperatures consistently exceed 86 F for six hours or more.

Management

Limiting powdery mildew is best approached by integrating resistant varieties, sourcing clean planting material, following crop sanitation practices, limiting early season disease establishment, optimizing fertilization and irrigation, and well-timed fungicide applications. While you may not be able to select resistant varieties because of market factors, some resistant varieties are available. The reaction of a hop variety to powdery mildew varies depending on where it is grown and which isolates of the fungus are present. Generally, Columbus, Cashmere and Galena are considered susceptible; Centennial and Chinook are intermediate; Nugget, Newport and Cascade are resistant, although races of the fungus present in Pacific Northwestern U.S. can overcome the resistance in the varieties as well.

Begin managing powdery mildew in early spring by thoroughly removing all green tissue during pruning. The goal of this early pruning is to remove the hard-to-locate flag shoots and delay or prevent infection. Eliminating flag shoots and early season disease requires removing all shoots, including those closest to the ground, on sides of hills and around poles or anchors. Mechanical pruning has been shown to be more effective than chemical pruning in eliminating flag shoots.

Pruning has not been widely adopted in Michigan, but should be considered to minimize risk, particularly if you are experiencing intense powdery or active infections are reported in the region. Avoid pruning and removing basal foliage on baby hop plants (less than 3 years old). For more information on pruning, refer to the MSU Extension article, “Pruning hops for disease management and yield benefits.”

Regular fungicide applications are needed to prevent infection and are applied regardless of visible symptoms. Appropriate timing of the first fungicide application after pruning is important to keep disease pressure at manageable levels. This application should be made as soon as possible after shoots reach 6-10 inches or regrow in pruned yards. Different fungicides are utilized for powdery mildew control during three distinct periods of the season: emergence to mid-June; mid-June to bloom; and bloom to preharvest. The Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) mode of action classification codes are included to help growers make resistance management decisions.

Emergence to mid-June

Consider a combination of applications of sulfur (FRAC M2), oils, Flint (trifloxystrobin, FRAC 11), Rhyme (flutriafol, FRAC 3), Procure 480 SC (triflumizonle, FRAC 3) or Unicorn DF (tebuconazole + sulfur, FRAC 3 + M2). Under high pressure, tank mix with oils and integrate copper (FRAC M1) into your downy mildew programs when possible. Avoid tank mixes of copper and sulfur, as phytotoxicity may occur.

Mid-June to bloom

Consider Rhyme (flutriafol, FRAC 3), Procure 480 SC (triflumizole, FRAC 3), Luna Experience (fluopyram + tebuconazole, FRAC 7 + 3), Vivando (metrafenone, FRAC 50), Gatten (flutianil, FRAC U13) and Torino (cyflufenamid, FRAC U6). Under high pressure, tank mix with oils and integrate copper into your downy mildew programs when possible.

Bloom to preharvest

Use a combination of Quintec (quinoxyfen, FRAC 13, 21-day preharvest interval), Pristine (pyraclostrobin + boscalid, FRAC 11 + 7, 14-day preharvest interval), Luna Sensation (fluopyram + trifloxystrobin, FRAC 7 + 11, 14-day preharvest interval), Vivando (metrafenone, FRAC 50, 14-day preharvest interval), Gatten (flutianil, FRAC U13) and Torino (cyflufenamid, FRAC U6, 6 day preharvest interval).

Many fungicide programs can give adequate disease control on leaves when applied preventively under low disease pressure. On cones, however, differences among fungicides are substantial. Mid-July through early August is an essential disease management period. The fungicide Quintec (quinoxyfen), Luna Sensation (fluopyram + trifloxystrobin), Vivando (metrafenone), Gatten (flutianil, FRAC U13) and Torino (cyflufenamid) are especially effective during this time and should be utilized in regular rotation when burrs and cones are present.

Fungicide applications alone are not sufficient to manage the disease. Under high disease pressure, mid-season removal of diseased basal foliage delays disease development on leaves and cones by lowering inoculum and increasing airflow. Do not apply desiccant herbicides until bines have grown far enough up the string so that the growing tip will not be damaged and bark has developed. In trials in Washington, removing basal foliage three times with a desiccant herbicide (e.g., AIM) provided more control of powdery mildew than removing it once or twice. Established yards can tolerate some removal of basal foliage without reducing yield. This practice is not advisable in baby plantings (less than 3 years), and may need to be considered cautiously in some situations with sensitive varieties such as Willamette. The potential for quality defects and yield loss increases with later harvests when powdery mildew is present on cones.

Management for organic growers

The cultural recommendations above apply to both hops produced for conventional commercial markets and those grown under guidelines for organic production. Under the additional constraints imposed by organic production guidelines, particular attention must be paid to selection of disease-resistant varieties. Available fungicide options for organic production are minimal but would include products in FRAC code 44 (biopesticides), FRAC P5 and P7 (host plant induction) and various oil based products (e.g., Trilogy). These products are generally not effective under high disease pressure, making organic production very challenging.

In order to make these softer products have the capability to control powdery mildew, frequent applications would be required in organic production systems with prophylactic applications occurring on less than seven-day intervals. Organic producers should consider a sulfur or oil-based fungicides. Do not tank mix sulfur and oil due to phytotoxicity issues. Although frequently cited in popular literature, optimal fertilization, soil health and water management alone are inadequate for disease control. Likewise, biorational compounds, manure teas and various botanicals and natural products have shown minimal to no efficacy against this pathogen under moderate to severe disease pressure.

Stay in touch

Want to receive more pest management information for hop this season? Sign up to receive the MSU Extension Hops & Barley Newsletter or follow us on Facebook. Also, join us this summer for monthly Live Hop Production Webinar Series.

This work is supported by Project GREEEN and the Crop Protection and Pest Management Program 2017-70006-27175 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Print

Print Email

Email