Protecting the Kirtland's warbler with jack pine forest management

MSU's David Rothstein and a team of researchers from Michigan Technological University and Wayne State University are working to ensure the sustainability of the Kirtland’s warbler population.

More than 10,000 years ago, Michigan was covered by glaciers. When the massive sheets of ice receded, they left behind landforms and sediments that created a multitude of diverse ecosystems. In the northern portion of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, huge volumes of glacial meltwater gave way to deep, sandy soils that support expansive areas of jack pine forests today.

Jack pine is a forest species that thrives in dry, fire-prone and nutrient-poor conditions. In turn, these forests support unique fauna and flora adapted to this extreme environment. Fire played an important role in leveling and rejuvenating the jack pine landscape until the region was settled by the Europeans. Once fire was taken out of the ecological equation, the habitat became unsuitable for many wildlife species, particularly the Kirtland’s warbler.

Named after Jared P. Kirtland, a naturalist who founded the Cleveland Academy of Natural Sciences, the Kirtland’s warbler is a small bird that lives half of the year in a handful of counties in Michigan’s northern Lower Peninsula and winters in the Bahamas. Very small pockets of the bird have been spotted in the Upper Peninsula, Wisconsin and Canada.

In 1967, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) added the bird to the endangered species list. A recovery effort began in the mid-1970s and continues today, led by the USFWS, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) and the U.S. Forest Service. By all accounts, it has been a resounding success — so much so that the USFWS is moving toward delisting the species as endangered.

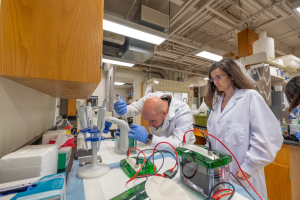

Michigan State University Department of Forestry professor David Rothstein and a team of researchers from Michigan Technological University and Wayne State University are working to ensure the sustainability of the Kirtland’s warbler population. The researchers — more than halfway through a project funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture — say there has been progress, but there are obstacles ahead.

“It’s exciting to see the bird move toward delisting because that means the recovery effort has been largely successful,” Rothstein said. “However, delisting does not mean that we can walk away from efforts to manage for Kirtland’s warbler habitat. In the absence of a natural fire cycle, this species is completely reliant on management, and if we don’t continue that management, we could end up in the same spot we were many years ago.”

As part of the recovery plan, 150,000 acres in Michigan have been dedicated to the Kirtland’s warbler. The birds flourish in jack pine stands that are roughly 5 to 20 years old. Once the stands have matured beyond that point, the trees are too large because limbs close to the ground that help to conceal the nests have died.

Since the early 1980s, new warbler habitat has been continuously regenerated by logging older jack pine stands and replanting them to maintain the more than 30,000 acres necessary for nesting. Jack pine forests aren’t known for their timber quality, but the Kirtland’s warbler recovery efforts have been aided by timber sales.

Rothstein said that nearly all of the original timber has been harvested, causing a snag in the project. Trees must be a certain diameter to be considered viable saw timber. Anything smaller is used as pulp wood for paper products or chips for burning as a renewable energy source. Logging companies are interested in the most valuable timber, and with the low prices of natural gas and other fossil fuels, selling wood for energy purposes is bringing diminishing returns.

“The original trees that were here served an important purpose for timber sales,” Rothstein said. “They were relatively large trees that could be used for saw logs. Now that we have worked through the majority of the 150,000 acres, there isn’t much of that mature forest left. Anything we’re cutting down in the future will probably have to be used primarily for chips because it’s not large enough. At this point, that’s not a sustainable financial model.”

Rothstein explained that the jack pine stands are planted specifically for Kirtland’s warbler, and that differs from a plantation design more suited to tree growth for timber purposes. For the bird, trees are strategically placed in numerous dense groupings with grass and other vegetation woven throughout.

The close proximity of the trees creates increased competition for water and nutrients, a situation that produces smaller trees than if they were planted at a lower density. Because roughly 20 percent of space is unutilized in the plantings, less trees are available for harvest. But researchers have some ideas.

“The current plan is to let these plantations grow for 50 years, but our data show that they achieve peak biomass nearly 20 years prior to that,” Rothstein said. “We’re looking at ways to manage the forests differently, perhaps harvest a portion of these stands at 30 years and replant. That would regenerate warbler habitat and allow us to extend rotation ages in other areas with the goal of producing higher value timber.

“Another possibility is that, after the birds leave a group of trees, we could thin the forest a bit and allow those trees that are left to grow larger and maybe become quality timber. There are many options on the table.”

Most endangered species, including Kirtland’s warbler, have a recovery team. Rothstein is a member of the breeding ground subgroup tasked with developing solutions for maintaining sustainable warbler habitat. To avoid a lapse in management once the bird is removed from the endangered species list, the USFWS, MDNR and U.S. Forest Service have entered into a memorandum of understanding that ensures each agency will contribute resources after delisting for additional work.

“There is a lot of complexity surrounding this situation,” Rothstein said. “If we don’t manage the forests here in Michigan, the bird will become extinct. It’s really that simple. We expect a lot from these forests from economic and recreation perspectives as well, so it’s a knot we’ll have to untie to make sure all of these priorities are treated appropriately.”

Print

Print Email

Email