MSU awarded $2.1 million grant to study chemical effects on women's health post-pregnancy

A team of scientists led by MSU researcher Rita Strakovsky has been awarded a five-year, $2.1 million NIH grant to study the long-term effects of phthalate exposure on mothers four to seven years after giving birth.

EAST LANSING, Mich. — A team of researchers from Michigan State University and the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) led by Rita Strakovsky, an assistant professor in the MSU Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, has been awarded a five-year, $2.1 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). They will be studying the long-term effects of phthalate exposure on mothers four to seven years after giving birth.

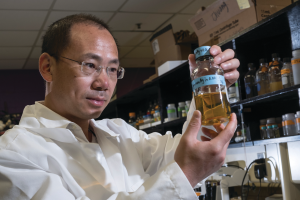

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, phthalates are a class of chemicals that increase the durability and flexibility of many common plastic products, including food packaging materials. Phthalates are also used in personal care products as scent and color stabilizers.

In previous studies, phthalates have been shown to disrupt endocrine system function, which is responsible for the production of hormones that regulate growth, development, metabolism and several other important physiological processes.

The new project will expand on the Illinois Kids Development Study (I-KIDS), a large pregnancy cohort study that began at UIUC in 2014 and evaluates the effects of environmental chemical exposure on children’s development from birth to age 5. Susan Schantz, a professor and environmental neurotoxicologist at UIUC, leads the I-KIDS project.

Strakovsky’s involvement with I-KIDS began while she was a postdoctoral researcher at UIUC before joining MSU. She was previously awarded an NIH grant to investigate phthalate exposure and hormonal disruption in pregnant women who participate in I-KIDS.

“Up to this point, we have been primarily concerned with endocrine disruptors and child development,” Strakovsky said. “We have been focusing on the developmental origins of health and disease, a concept that suggests a person’s health throughout life is heavily influenced by environmental exposures in utero and in early childhood.

“The question we have now is, what about the mother’s health? Estrogen and other reproductive hormones are important for women’s metabolic and cardiovascular health, so our goal is to understand the potential consequences of hormonal disruption.”

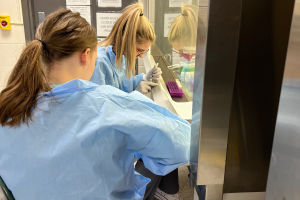

Roughly 350 mothers from I-KIDS will be reenrolled for the new project and will meet with researchers four to seven years after giving birth.

Several health indicators will be evaluated, such as body composition, resting energy expenditure, blood pressure, levels of reproductive hormones and levels of various blood markers of metabolic and cardiovascular health. The mothers will also be surveyed on topics such as sleep habits, diet, physical activity, emotional state, socioeconomic status and stress level.

“We know that pregnancy has important implications for women’s long-term metabolic and cardiovascular health,” Strakovsky said. “What we want to determine now is whether exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals during pregnancy adds another layer of complexity for women postpartum, such as the inability to lose weight after pregnancy or additional postpartum weight gain, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or any number of other health-related issues.”

Due to the novel coronavirus pandemic, mothers cannot be contacted for in-person meetings currently, but Strakovsky is hoping that changes soon.

“It’s critical for us to get these measurements, and some of the mothers are already reaching their eligibility window,” she said. “But safety for everyone is our first priority, so we’ll adjust accordingly.”

Print

Print Email

Email